BLOG

The BIAAS blog series features posts by junior and senior scholars in the field of Austrian-American studies. The views and opinions expressed in these blogs are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of BIAAS.

BIAAS Austrian-American Blog

Raptured and demonized: Josephine Baker in Vienna

By Mona Horncastle

In 1928, after two successful years in Paris, Baker starts her first tour of Europe with great expectations. Yet her victories are always accompanied by controversy. In Vienna, the first stop on her journey, Baker is omnipresent: posters advertising her second film La Revue des Revues show the almost naked Baker in pearls and feather jewelry throughout the city. The poster for her revue Black and White is no less revealing. Vienna is not Paris, and the entertainment culture of the Music Hall is still completely foreign to the city, which leads to agitation among cultural conservatives: Catholic circles mobilize before Baker even arrives in Vienna. When her train from Paris arrives, the church bells of the Paulanerkirche are chiming to warn the population of the "Black Devil." However, an unfazed crowd gathers to cheer enthusiastically as Baker arrives on the platform of the train station. The authorities are also ambiguous: on the one hand, Baker is promised police protection for the duration of her stay in Vienna, on the other hand, the Ronacher Theater is not permitted to show the announced revue.

Transatlantic Journeys in Musical Practice

with Christiane Tewinkel

In this podcast, Dr. Christiane Tewinkel shares many fascinating aspects of her musicology research as related to Theodor Leschetizky and his American students. Born in Galicia in 1830, Theodor Leschetizky, a pianist and composer himself, became internationally famous as a piano teacher with over 1,000 students, including Fanny Bloomfield-Zeisler, Elly Ney, Ignacy Paderewski, and Arthur Schnabel.

Although Leschetizky had enormous influence during his time, his personal records had never been studied. That is, until now. Christiane Tewinkel traveled to the Leschetizky Association in New York to see their special collection for herself.

VOICES

Leaving Siegfried Behind: Reimagining Monuments in Austria and the American South By Alexandra Sterling-Hellenbrand

A solitary stone figure occupies a prominent space at the institutional heart of the university. The statue commemorates the lives, primarily of students, tragically cut short on the battlefields of a war that ended in defeat. The memorial testifies to the continuing significance of that lost cause; the figure’s presence allows that past to intrude constantly into the present, allows that past to insist on keeping its narrative and its problematic memory current for successive generations. Each generation, in its respective present, must wrestle with the legacy of the past for which the memorial stands, a past that becomes increasingly contentious over time, as times change.

A Sense of Belonging: The Camphill Movement and its Origins—A Two-Part Podcast Series

with Katherine E. Sorrels

The Camphill Movement is a global network of intentional communities for abled and intellectually disabled people. With over 100 communities today, Camphill began after Dr. Karl Koenig, his wife Tilla, and a group of volunteers fled Nazi-occupied Vienna in 1938 and rejoined in Aberdeen, Scotland in 1939. There they undertook the care of Austrian- and German-Jewish refugee children, as well as British children, with disabilities. From that first Camphill Special School, a fusion of Jewish diasporas with Austrian and German spiritual movements and the U.S. counterculture all developed Camphill's extraordinary approach to disability.

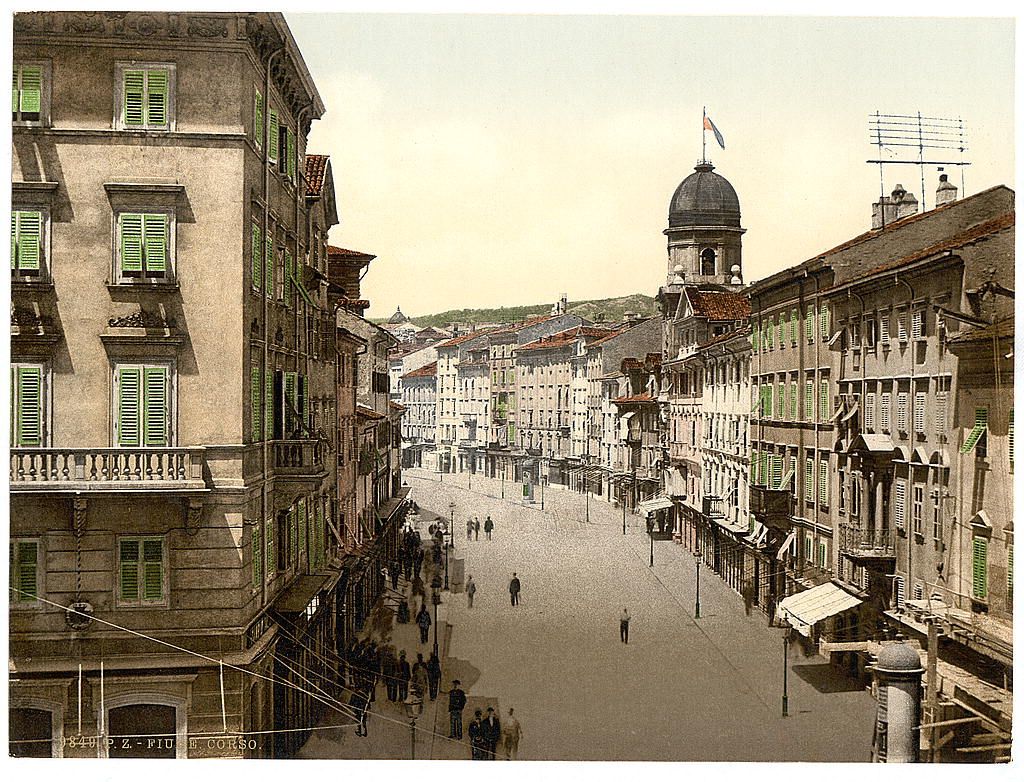

The Fiume Crisis: Made (But Not Primarily) in the USA

By Dominique Kirchner Reill

What would have happened if Woodrow Wilson and his corps of American experts had focused less of their post-WWI energy on the northeastern Adriatic port town of Fiume? Perhaps the Paris Peace Conference would not have collapsed in diplomatic deadlock, leading to the only Great Power walk-out of the entire proceedings. Perhaps Japan would have been denied the mandate over mainland China. Perhaps two successive Italian governments would not have fallen apart. A charismatic dictator-poet might not have founded a rogue republic in the city. Italian pirates might have idled on the Adriatic, instead of attacking ships and scoring booty to fund the poet’s Fiume regime. Peace might have reigned then, in Fiume, over the 1920 Christmas holiday with no need to chase out said poet and his followers. Perhaps Fiume would not have become the smallest successor state of post-WWI Europe. And perhaps all the nationalist extremism that percolated around this upheaval wouldn’t have convinced so many Italians that only Mussolini with his militaristic takeover would deliver Italy the expansionist, national grandeur so many believed it deserved. And, finally, perhaps today the city, today’s Rijeka in the Republic of Croatia, would not have witnessed heart-wrenching histories of nationalist erasure where Slavic speakers and Jews suffered exclusionary politics and violence at the hands of the Fascist and Nazi regimes, followed by tens of thousands of Italians fleeing after Fascism’s fall in order avoid a similar fate.

Steel City Haydnsaal: The Austrian Nationality Room in Pitt’s Cathedral of Learning

By Kristina E. Poznan

Jutting skyward on the University of Pittsburgh campus is one of the tallest educational buildings in the world, the Cathedral of Learning. The 2,000-room Cathedral was commissioned in 1921 and began hosting classes in 1931. In addition to the academic and administrative departments housed in this building, it contains over two dozen instructional spaces each designed to celebrate a different culture that had an influence on Pittsburgh's growth, reflecting the significance of the city’s immigrant population. European states, through local organizing committees, were granted the opportunity to decorate “nationality rooms” in the post-war era. The Cathedral as a whole was a unifying project, but the distribution of classrooms based on new political borders in Europe formally divided Pittsburgh’s immigrants. “Each group had to form a Room Committee, which would be responsible for all fundraising, designing, and acquisition.” Pittsburgh residents hailing from Austria-Hungary could be represented by the Czechoslovak Nationality Room (1939), German Nationality Room (1938), Hungarian Nationality Room (1939), Polish Nationality Room (1940), Romanian Nationality Room (1943), and Yugoslav Nationality Room (1939). (An Israel Heritage Room was added in 1987 and a Ukrainian Room in 1990). This method of division stands in contrast to that employed by the Cleveland Cultural Gardens, which apportioned spaces by ethno-linguistic cultures, rather than by country.