Raptured and demonized: Josephine Baker in Vienna

By Mona Horncastle

“In the end, there is only one race: the human race.” -Josephine Baker

When Freda J. McDonald is born in a slum in Saint Louis in 1906, it is unthinkable she will become the first African American superstar to conquer the world as Josephine Baker. The illegitimate daughter of a laundress, her chances of reversing the laws of racial segregation are slim. However, Baker never sticks to rules; she always does her own thing.

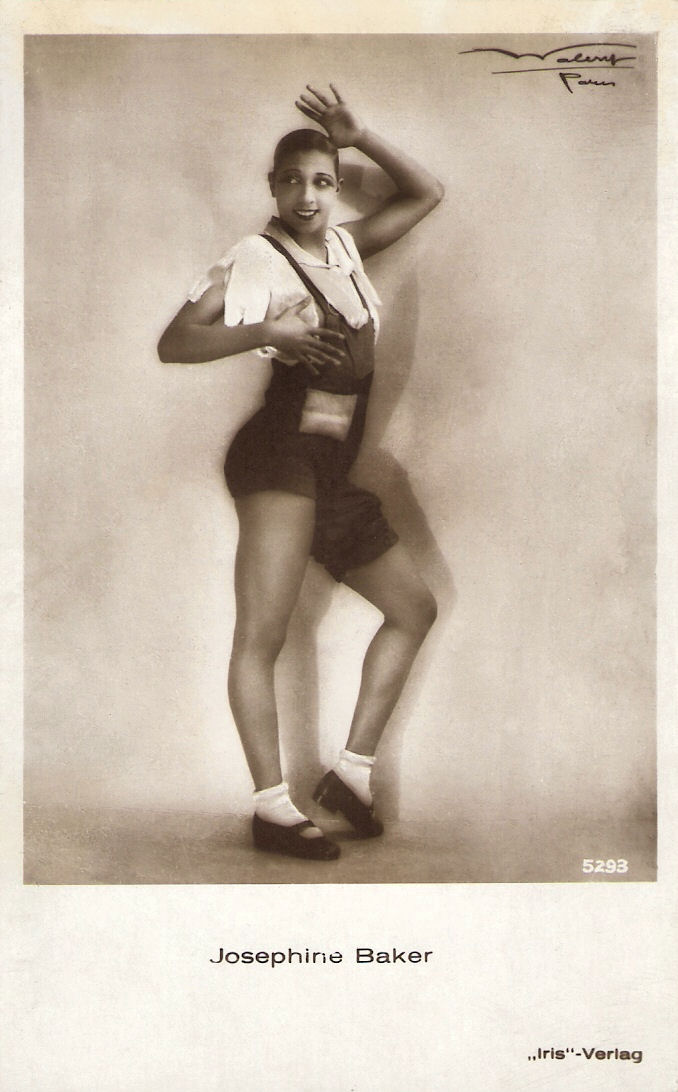

Josephine Baker.

In 1928, after two successful years in Paris, Baker starts her first tour of Europe with great expectations. Yet her victories are always accompanied by controversy. In Vienna, the first stop on her journey, Baker is omnipresent: posters advertising her second film La Revue des Revues show the almost naked Baker in pearls and feather jewelry throughout the city. The poster for her revue Black and White is no less revealing. Vienna is not Paris, and the entertainment culture of the Music Hall is still completely foreign to the city, which leads to agitation among cultural conservatives: Catholic circles mobilize before Baker even arrives in Vienna. When her train from Paris arrives, the church bells of the Paulanerkirche are chiming to warn the population of the “Black Devil.”[1] However, an unfazed crowd gathers to cheer enthusiastically as Baker arrives on the platform of the train station. The authorities are also ambiguous: on the one hand, Baker is promised police protection for the duration of her stay in Vienna, on the other hand, the Ronacher Theater is not permitted to show the announced revue.

Not only in Vienna but during her entire tour through Europe, Baker must deal with a difficult and hurtful variety of allegations. In addition to racist hostility, her talent is questioned, her success is criticized, and she is accused of endangering public morality. This is not merely a political issue for Baker: In the Austrian parliament, there is an exchange of blows between Christian Socialists and Liberals. Anton Jerzabek, the Christian Social Member of the National Council, calls for a ban on the “pornographic dance performance.” According to the official parliamentary reports, Jerzabek is in the fray, which is documented in the report of the assembly: “You have all seen this certain poster that depicts a certain lady in natural costume. (Lively cheerfulness.) For she has nothing else to wear but a string of pearls around her waist and a few ostrich feathers attached to her sides. (Renewed lively cheerfulness.) The obverse and reverse sides, on the other hand, are completely bare. What you find there as cover, you could call a postage stamp, but it is not clothing. This is perhaps still common in the interior of the state of Congo but was worn in our regions only during the time of the cave bears, and even there only in midsummer.”[2] Adalbert Graf Sternberg, the representative of the Liberals, defends Baker’s dance and her nudity as symbols of freedom and basic humanistic values and even goes so far as to point out that God created man naked; thereby challenging the concept that nudity was blasphemous.

Ultimately, the conservative forces succumb, and Baker opens in the Johann Strauss Theater in front of a packed house on March 1st. She presents herself with aplomb, wearing an elegant evening gown for her first act singing Pretty Little Baby. The performance is sold out for weeks. The mood remains heated, and it soon takes some unexpected turns: Special services are being held in church to strengthen the morale of the faithful. However, this does not always have the desired effect. On the morning of March 1, the Jesuit priest Fey preaches with such dedication against the immorality of Baker that more than just a few buy a ticket for the performance after the service – his description of the dancer as the embodiment of decadence turned out to be the best advertisement.

Austrian Postcard of Josephine Baker.

How can it be explained that Baker must endure being portrayed either as the “Black Venus” or as the “Black Devil,”[3] while never being portrayed simply as a woman and an artist without reference to her skin color? The answer has to be studied in the context of her time. As always, Baker retains her composure: “People of color are not forced to provoke. The incidents happen all by themselves.”

At the beginning of the 20th century, there is no collective awareness of the inhuman injustices of racism in both the US and Europe. Baker is her own benchmark, shaped by three important experiences she made concerning her skin color when she was growing up:

- All her family members have very dark skin except for her, which makes Baker an outsider in her family.

- In 1917, she witnesses the race riots in East St. Louis, which are considered among the worst in American history to this day. Baker is 11 when she first realizes that the color of her skin is life-threatening.

- In 1920, Baker determines there are only three possible careers for a Black girl in a slum: maid, prostitute, or dancer.

Baker chooses the last option, about which she later says: “I became a dancer because I was born in a cold city and I have frozen terribly during my entire childhood.”

In fact, it is her success in being “the funny girl at the end of the chorus line,” where she draws attention to herself by stepping out of line. Stepping out of line becomes her life motto, a brand she exploits to become the first Black superstar in Europe. “Crazy and wicked” works marvelously as a principle of success. Baker recognizes this and continues to present herself as “erotic and exotic.” By today’s standards this is unimaginable and politically anything-but-correct: However, accepting the label “sexy, black, and amusing” and owning it for herself is the lesser evil for Baker at the time. In a world full of racism and prohibition, Baker chooses to display her beauty and individuality boldly. She is fearless forever in all the images that remain.

Unfortunately, those very images preserve Baker as the “dancer in the banana skirt,” but don’t tell the full story of her legacy. Few people know that she is a freedom fighter – as a troop entertainer she is in no way inferior to Marlene Dietrich – with one great difference: Baker insists she will only entertain the troops if there is no segregation in the audience. This is her first triumph in using her fame, and therefore her power, to get the people around her to treat everyone as human beings. This early recognition is based on her own experience: respect and freedom are general human rights, regardless of religion, nationality, or skin color.

Regrettably, this side of Baker remains little known. She is awarded three high medals by Charles de Gaulle for her work as a spy and troop entertainer in World War II. While touring the US in 1951, she enforces that there would be no racial discrimination in the audience – for the first time in American history, clubs are open to all Americans. This is the time when Baker also gets involved with the civil rights movement. When the March on Washington is being organized in 1963, it is Martin Luther King himself who invites Baker to give a speech.

After she dies in 1975 at the age of 69, she receives a state funeral for her long-standing equal rights activism.

“In the end, there is only one race: the human race,” Baker would say. In the end, this is true for her. A staggering 20,000 people of all races gather to follow her funeral procession through Paris, remembering her not only as an entertainer, but as the icon she becomes for her commitment to equal rights.

Author Biography

Mona Horncastle is a cultural scientist, writer and founder of a non-profit company for educational projects. She lives and publishes in Germany and Austria. In 2018 upon writing the first comprehensive biography about the most important artist of the turn of the century, Gustav Klimt (Brandstätter Verlag, Vienna), she continues discovering the untold lives and achievements of outstanding personalities. In 2019 she revealed the importance of the architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky (Molden Verlag, Vienna) who invented the first equipped kitchen after her important role in the early development of social buildings. Horncastle’s latest publication is Josephine Baker. World star. Freedom fighter. Icon. (Molden Verlag, Vienna, ISBN 978-3.222.15046-3).

Notes

[1] In contemporary sources words which are now recognized as discriminatory are used. The auther is quoting those in marks to convey the historical truth. The author and the publisher expressly point out that these racist terms do not correspond to their own attitudes.

[2] Neues Wiener Journal, Feb. 25.1928, page 4.

[3] Josephine Baker’s career is accompanied by labels which either demonize her or rapture her as the beauty ideal of the goddess of love. These contemporary phrases are perceived as racist today.

Published on March 9, 2021.