VOICES

Leaving Siegfried Behind: Reimagining Monuments in Austria and the American South

By Alexandra Sterling-Hellenbrand

The Past in the Present: Vienna and Chapel Hill, North Carolina

A solitary stone figure occupies a prominent space at the institutional heart of the university. The statue commemorates the lives, primarily of students, tragically cut short on the battlefields of a war that ended in defeat. The memorial testifies to the continuing significance of that lost cause; the figure’s presence allows that past to intrude constantly into the present, allows that past to insist on keeping its narrative and its problematic memory current for successive generations. Each generation, in its respective present, must wrestle with the legacy of the past for which the memorial stands, a past that becomes increasingly contentious over time, as times change.

This description applies to both statues I would like to explore in this essay. The first is the so-called Siegfriedskopf in its original placement in the entrance hall to the main administration building of the University of Vienna. The second is a monument that until recently used to stand on the campus of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: the statue known as “Silent Sam.” As a professor of German language and literature who specializes in medieval literature and its reception (Mittelalterrezeption), I must confess that the history of the American South has until now only remotely touched my scholarly consciousness. However, for almost 20 years I have lived North Carolina. I teach at Appalachian State University, a campus in the University of North Carolina system. The system’s flagship institution, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has drawn attention for demonstrations and controversy surrounding Silent Sam, a statue dedicated in 1913 to the students who died in the Civil War. During the Covid-lockdown of summer 2020, having had to return prematurely from a planned Fulbright semester in Austria and teaching a course at the University of Graz on the “American Middle Ages” from my home office in the Blue Ridge Mountains, I found the South and Austria colliding in unexpected ways.

Interestingly, I had not connected the Siegfriedskopf and Silent Sam until the events of June 2020 turned a bright spotlight on a third space: Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia, an opulent boulevard lined with memorials that represent the Confederacy’s “heroes.” Photographs show, for example, how the monument to Robert E. Lee changed over the course of Black Lives Matter demonstrations. The ground around it became a colorful tapestry of signs and posters and people. Visitors sat on the pedestal with signs, musicians played impromptu concerts. The statue itself was covered with placards, posters, tape—colors, slogans, words, prayers, symbols—all of which communicated messages that counter the symbolism of the monument itself. These messages confront the history that the monument represents, inserting other (his)stories, lifting different voices. The images and words that enveloped the Lee monument, from “Black Lives Matter” to “peace” to the name “George Floyd” at least temporarily infused the cold stone of the past with the vibrant intensity of now. [1]

Robert E. Lee Monument, Richmond, VA, June 2020. Photo Credit: Larissa Tracy, with permission

The spontaneous re-contextualizations of the Lee monument clearly show us the strength of different (his)stories demanding to be heard. This brings me back to the comparison I want to explore between the Siegfriedskopf and Silent Sam. Susan Neiman has suggested that monuments are “values made visible.”[2] Memorials literally embody “the ideals we choose to honor” and, in choosing to memorialize a historical moment, “we are choosing the values we want to defend and pass on.”[3] When we compare the recent fates of the two monuments, we can see that they illustrate the repercussions of difficult history within each community. The monuments clearly reflect the challenges and the values their communities wrestle with today.

Silent Sam: Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Let me turn first to the statue known as Silent Sam. Silent Sam was dedicated at McCorkle Place on the campus of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1913. The total ensemble reached a height of 17 feet: an eight-foot-tall figure of a young man in Confederate uniform stood atop a pedestal that itself was nine feet. Erected in 1913 and placed prominently at the main entrance of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the statue commemorated the 1000 students who fell in the Civil War fighting for the Confederacy. Like the statue of Robert E. Lee in Richmond, Silent Sam was part of the extensive building program supported by the Daughters of the Confederacy, a group that promoted the mythology of the South’s moral victory (the Lost Cause) in the American South and further entrenched racist attitudes in first half of the twentieth century.[4] Like the Siegfriedskopf, the statue of Silent Sam remained in its place of honor before the university’s doors for decades with the support of conservative legislators and alumni despite protests in the 1960’s. At the university’s doorway, the statue had become a fixture on the campus, a meeting point, a rallying point, and a flashpoint for controversy. In spring 2018, a UNC graduate student was arrested after having thrown red paint on the statue in an attempt to give it historical context and to challenge the white supremacy it represents.[5] In August 2018, in an increasingly tense situation, the statue was pulled off of its pedestal on the day before classes were to begin for the fall semester. Although the statue was eventually removed from the site and transferred to an undisclosed location, the university recommended keeping Silent Sam on the campus. The university cited a North Carolina state law from 2015 that prevented the removal of “objects of remembrance” from public property, although the state governor indicated the statue could be moved if it were a matter of public safety.[6] Tensions escalated, and protests continued in December 2018. In January 2019, the chancellor of the university approved the removal of the statue’s pedestal and other remnants, and then the chancellor resigned shortly thereafter. By the end of November 2019, the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill had agreed to a $2.5 million settlement with the North Carolina division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans; the group would use the settlement to preserve the statue by displaying it in a facility as yet to be planned and built.[7] The decision sparked a backlash and a series of legal challenges that eventually led the same judge who had approved the settlement to overturn it and thereby reverse the original decision.[8] As the statue currently remains in storage, the question of its fate remains unresolved.[9] After standing in such a prominent position to watch over the campus in Chapel Hill, Silent Sam has rather unceremoniously disappeared from view.

Silent Sam Removed From Pedestal, Chapel Hill, NC, 8 Aug 2020. Hameltion, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

The Siegfriedskopf: The University of Vienna

Like Silent Sam in Chapel Hill, the Siegfriedskopf no longer occupies its original location in the university’s entrance hall. Unlike Silent Sam, however, the Siegfriedskopf has not vanished. On the contrary, rather than remove it entirely, the university decided to incorporate the monument into a twenty-first century statement affirming tolerance and condemning prejudice and violence.

The sculpture known as the Siegfriedskopf was dedicated to fallen heroes of the University of Vienna (“den Gefallenen Helden unserer Universität”) during WWI. From its unveiling on November 9, 1923, until 2006, it resided in the university’s central entrance hall as a towering symbol of anti-semitism. In 2006, the sculpture was finally moved from its location to the arcaded courtyard or Arkadenhof. Christoph Gnant suggests that the Universities Act of 2002 played a significant role in giving the university the autonomy it needed in order to “consciously face up to its historical responsibilities.”[10] The Siegfriedskopf had been a source of contention for decades: a meeting point for nationalist fraternities and student groups, a magnet for both the Right (attraction) and the Left (repulsion). Following a proposal made during the memorial year 1988 to commemorate the victims of the Nazi era by a memorial plaque in the Aula, the university senate decided in 1990 that the Siegfriedskopf be moved into the arcaded courtyard. A plaque was to be installed in the entrance hall which would serve as a memorial for “the victims of war and violence with genuine grief.” (Gnant 266) Progress on moving the sculpture stalled due to protracted debate in politics and in the media, to objections from the Bundesdenkmalamt, and to technical problems involving the actual physical transfer of the monument from one location to another. It took an act of vandalism in 2002, an auspicious anniversary, and a renewed commitment by the university administration before the hitherto unfulfilled mandate was finally carried out.

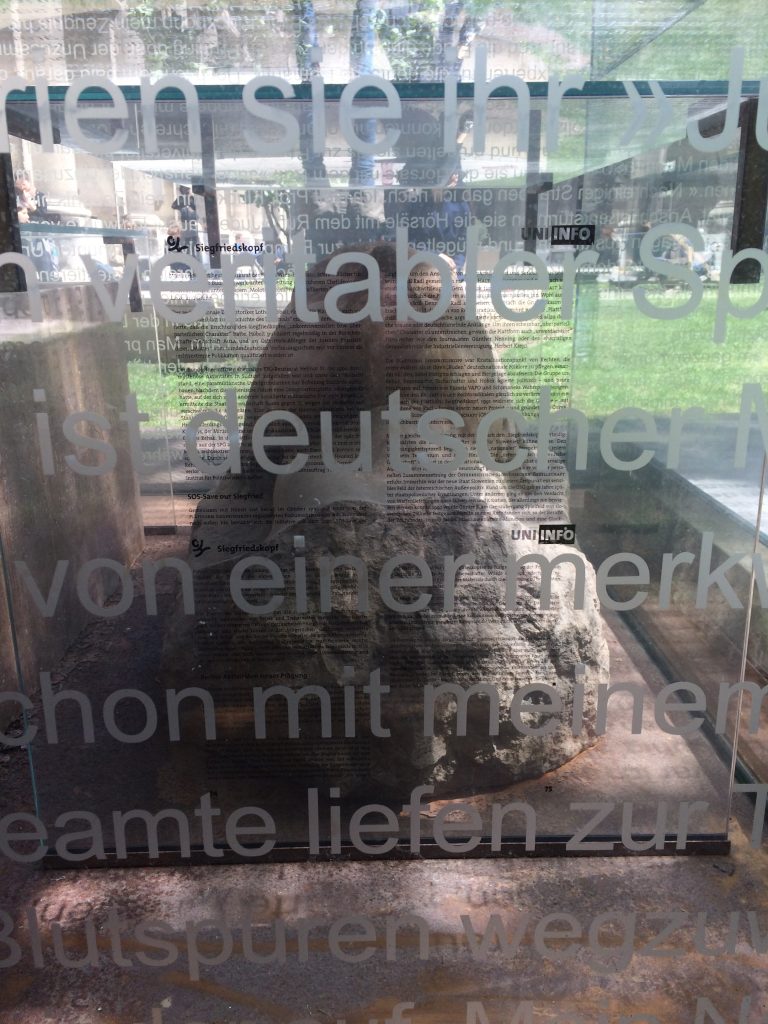

Siegfriedskopf, Vienna, Austria, May 2019. Photo by author.

The monument was not only moved; it was reimagined and recontextualized in an innovative concept designed by the studio of Bele Marx and Gilles Mussard (Büro Photoglas). The artists offer an extensive description of their work with textual references in their publication (“Kontroverse Siegfriedskopf”).[11] A short summary will suffice here. In a critical move, the new installation dismantles the previous sculpture into its three parts: the head, the pedestal and the plinth. Text dominates the monument now, covering the transparent cubes that encase the three original pieces. When I first saw the Siegfriedskopf in May 2019, I walked around the monument’s grassy plot near the covered walkway lined with busts of famous scientists and university elite. I found myself frustrated because I could not clearly see the image of Siegfried’s head to take a picture–only to realize that, of course, this is the point. The medium here is the message, to coin a phrase: in the new installation, the words obscure the images. Thus, the sculpture now expresses clearly what had previously been unsaid and unacknowledged. Words have been weapons; they have obfuscated, manipulated, injured—and the Siegfriedskopf only served to amplify those messages. Now words cover the images, literally recontextualizing them, and those words are then in turn encased in yet another story. The head has text from articles in the Arbeiter-Zeitung from October and November 1923 regarding Hakenkreuzterror at the university. The pedestal has text from the 1990 debate about the monument in the context of right-wing extremism at Austrian universities. And the plinth displays portions of another article that details the debates of the 1990s about the head of the German hero Siegfried. On the weather-resistant glass cube that contains the now tripartite display, we have a text by Minna Lachs who describes an experience she had as a young Jewish woman student at the university in the 1920s where a stranger helped her exit the Reading Room safely during a violent demonstration that had begun around the Siegfriedskopf in the entrance hall.[12] The emphasis on text should remind us of the power of words not just to damage or injure but to resist— words tell and record history in general, far beyond the history of this or any particular monument. And we must remember that words and books are often the first victims of totalitarian regimes, to paraphrase Angelika Bäumer’s dedication speech for the new installation in July 2006.[13] In its new location, with its new design, the Siegfriedskopf shows the university’s attempt to acknowledge its difficult past, to transform that past into a different narrative for the future. The Nibelung mythology is part of that past, deeply embedded in nationalistic discourse from the 19th century onward. Many scholars have sought to rehabilitate the narrative and the imagery of the Nibelungen in the last decades, after its misappropriation reached a zenith in the Nazi propaganda before and during World War II. The re-configuration of the Siegfriedskopf demonstrates the process of telling new stories out of tired older tales fraught with conflict; whereas the original sculpture evoked memories of racism and violence, the new installation rehabilitates the Siegfriedskopf; it allows us to confront and interrogate the past, to ask questions that can open further dialogue. Thus the University of Vienna, and perhaps also Austria, can relegate the Siegfried of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to the archives and relate stories better suited to the present and future.

Siegfriedskopf detail, Vienna, Austria, May 2019. Photo by author.

Leaving Siegfried Behind: New Monuments for a Difficult Past?

The Siegfriedskopf needed to be moved from the space it occupied at the institutional heart of the university; it symbolized a legacy and a past that had become increasingly contentious over time. A comparable legacy applies to Silent Sam. After two years of controversy and legal wrangling, the question of Silent Sam has reached a kind of conclusion, though the future of the statue (like its current location) remains undetermined. The Siegfriedskopf, on the other hand, underwent an extensive transformation for which English lacks an appropriately nuanced term: the commemorative memorial (Denkmal) became a symbol of warning (Mahnmal), the latter much better suited to the monument’s purpose for the twenty-first century.[14] The process toward to a similar transformation is beginning in earnest in the American South; like the United States generally, the South is “in the midst of a long reckoning over our inherited monuments.”[15] In a broader context, we can place these monuments (literally) in the landscape of the “culture of remembrance” (Erinnerungskultur) that has impacted literary, cultural, and historical studies since the mid-twentieth century. Memories do not exist as closed systems, says Aleida Assmann; in any given social reality, memories intersect, they touch, they strengthen, they modify and they become polarized in connection with other processes of remembering and forgetting.[16]

The process of memory brings us back to the role of monuments: they portray for us a version of our past and thus, to return to the words of Susan Neiman, they make our values visible. Values must evolve as communities change over time. In summer 2020, the spontaneous re-configuration of the Lee monument in Richmond reminded me of the re-configured Siegfriedskopf which had compelled me to approach the monument differently, as all visitors must now do since the textual installation mediates both the physical and interpretive experience of the original monument. Accordingly, the monument encourages us to reassess the role of the past for the present; we should re-examine our expectations, and then we should take a second and a third look at the remnants of the past. In sum, the Siegfriedskopf challenges us to address and create different narratives. Such a challenge was embraced in Richmond when the Lee monument was literally overwritten by photos, poems, and posters, as Black Americans rehabilitated that space, if only for few days, in June. Instead of recontextualizing the statue of Silent Sam, however, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill simply removed it. Nevertheless, the discussion about Confederate monuments continues across the state, as cities and counties re-evaluate the commemorations of numerous street names, historical plaques, and statues. The United States has much to learn as we confront the toxic legacy of the Confederacy. The Siegfriedskopf, like other Nibelung monuments in Austria, may show us a way forward – albeit perhaps far too halting at times—that productively accommodates uncomfortable conversations about the past.[17]

Siegfriedskopf, Vienna, Austria. 8 March 2015 Photo credit: Thomas Ledl CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0), via Wikimedia Commons

Author Biography

Alexandra Sterling-Hellenbrand is Professor of German and Global Studies at Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina. She is the author of two books: Topographies of Gender in Middle High German Arthurian Romance (Garland/Taylor and Francis, 2001) and Medieval Literature on Display: Heritage and Culture in Modern Germany (Bloomsbury, 2020). Her publications focus on Arthurian romance and on medieval German literature generally, as well as its modern reception. Recent projects include a co-authored article on women’s Arthurian scholarship in German for the Journal of International Arthurian Studies as well as an essay on the role of games and the ethics of play in Arthurian literature. The current essay is part of a larger project on heritage and visual representations of medieval literature in the contemporary Austrian landscape that began as part of a Fulbright project at the University of Graz in spring 2020.

Further Reading

Assmann, Aleida. Cultural memory and Western civilization: Functions, media, archives.

Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2011.

Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books, 2002.

Cox, Karen L. Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2019.

Cox, Karen L. Dreaming of Dixie: How the South Was Created in American Popular Culture. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Goebel, Stefan. The Great War and medieval memory: War, remembrance and medievalism in Britain and Germany, 1914-1940. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Heinzle, Joachim and Anneliese Waldschmidt, eds. Die Nibelungen. Ein deutscher Wahn, ein

deutscher Alptraum. Studien und Dokumente zur Rezpetion des Nibelungenstoffs im 19.

und 20. Jahrhundert. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1991.

Neiman, Susan. Learning from the Germans: Race and the Memory of Evil. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux 2019.

Peckham, Robert Shannan. Rethinking Heritage: Cultures and Politics in Europe. London: New York : I.B. Tauris, 2003.

Tracy, Larissa, “Fascism and Chivalry in the Confederate Monuments of Richmond.” June 11, 2020 https://www.publicmedievalist.com/confederate-monuments/

Links

Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina

https://docsouth.unc.edu/commland/

Southern Poverty Law Center: Confederate Monuments in the American South

https://www.splcenter.org/20190201/whose-heritage-public-symbols-confederacy

Siegfriedskopf

https://geschichte.univie.ac.at/de/artikel/denkmal-siegfriedskopf

https://www.hdgoe.at/siegfriedskopf

Notes

[1]Larissa Tracy, “Fascism and Chivalry in the Confederate Monuments of Richmond,” The Public Medievalist, June 11, 2020, https://www.publicmedievalist.com/confederate-monuments/ Accessed 15 November 2020.

[2] Susan Neiman, Learning from the Germans: Race and the Memory of Evil (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux 2019) 266.

[3] Neiman, 263.

[4] Karen L. Cox, Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2019)

[5] https://www.wunc.org/post/silent-sam-protester-vows-continue-contextualize-confederate-monument Accessed 14 November 2020.

[6] https://www.charlotteobserver.com/news/local/education/article181348661.html Accessed 15 November 2020

[7] https://www.chronicle.com/article/unc-will-give-silent-sam-to-a-confederate-group-along-with-a-2-5-million-trust/ Accessed 15 November 2020.

[8] https://www.chronicle.com/article/uncs-silent-sam-settlement-sparked-a-backlash-now-a-judge-has-overturned-the-deal/ Accessed 15 November 2020.

[9]In May 2020, after the lawsuit brought by the Sons of Confederate Veterans was finally dismissed, the statue was returned to the custody of the university; administrators confirmed that the monument will not be erected again on the campus. http://pulse.ncpolicywatch.org/2020/05/04/silent-sam-lawsuit-dismissed/ Accessed 15 November 2020.

[10]Christoph Gnant, “The Refurbishment of the Main Building Aula and Arcaded Courtyard at the Beginning of the Twenty-First Century,” in Sites of Knowledge: The University of Vienna and Its Buildings: A History 1365 – 2015 eds. Julia Rüdiger, Dieter Schweizer, et al. (Böhlau Verlag Wien, 2015), 265-270, 265.

[11] https://geschichte.univie.ac.at/de/artikel/kontroverse-siegfriedskopf Accessed 15 November 2020

[12] http://www.photoglas.com/deutsch/buero_frameset.php?a=1&id=35 Accessed 15 November 2020

[13] https://geschichte.univie.ac.at/de/artikel/denkmal-siegfriedskopf Accessed 15 November 2020

[14]Stefan Müller, “Ehre, Freiheit, Vaterland. Wie ein Denkmal dafür sorgte, dass sich die Universität Wien ihrer Vergangenheit stellte,” DIE ZEIT, 26 February 2015.

[15]Paul M. Farber and Ken Lum, “Preface,” in Monument Lab. Creative Speculations for Philadelphia, ed. Paul M. Farber and Ken Lum (Philadelphia, Rome, Tokyo: Temple UP, 2020), xv.

[16] Aleida Assmann, Der lange Schatten der Vergangenheit. Erinnerungskultur und Geschichtspolitik 2nd ed. (Munich: C.H. Beck, 2014), 17.

[17]Alexandra Sterling-Hellenbrand, “East Meets West? Heritage, Medievalism, and the Nibelungenlied on the Danube,” This Year’s Work in Medievalism 33 (2018) 1-10 https://sites.google.com/site/theyearsworkinmedievalism/all-issues/33-2018 Accessed 14 November 2020.

Published on January 19, 2021.