Mountain Rescue in Translation

by Mark S. Weiner

Why does the honor guard of the Mountain Rescue Association (MRA), the umbrella organization for all mountain rescue in America, carry Austrian ice axes when it stands in respect at memorials for fallen search-and-rescue personnel? For the past two years, I have been making a documentary film about the Austrian mountain rescue service, the Bergrettung, supported by seed funding from BIAAS. As I explained in an early interview about the project, my motivating premise has been that there’s something special about the service as a core institution of Austrian civil society that can lay bare the social and cultural needs of liberal democracy as a form of government, both in the United States and worldwide. But the film will also illuminate the impact of the Austrian service on America, so evident in MRA’s memorial ritual.

__________

When I began research for the film, I had a broad, unspecified sense that the Bergrettung had influenced mountain search-and-rescue in the U.S. After all, Austria was central to the development of mountain tourism in the late nineteenth century, and a systematized mountain rescue service developed there under the auspices of the German and Austrian Alpine Association beginning in 1902. But you can see the uncertainty that I had about how that influence traveled in my response to the third question posed in the BIAAS interview.

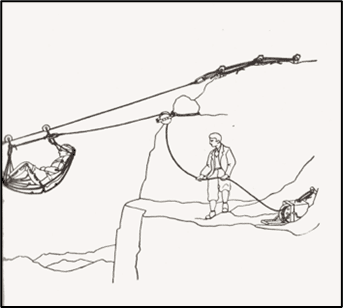

I now appreciate that the Austrian who exercised the greatest impact on modern American rescue practice was the engineer Sebastian “Wastl” Mariner (1909-1989), who led the Tyrolean service from 1956 to 1974. During the war, Mariner had worked with the Bavarian physician Fritz Rometsch at the Army Mountain Medical School in St. Johann, Tyrol to develop new rescue technology and techniques. What the two produced was revolutionary, as significant for the field back then as the use of the helicopters in mountain rescue would become in later decades. Their inventions—they were especially Rometsch’s—included a rig for lowering rescuers to accident victims from on high by means of a steel cable, which obviated the need to tie ropes together; the adaptation of the Norwegian Akja transport sled into a rescue toboggan suited for mountain use; and the development of a bowed, tubular stretcher in which patients could be lowered vertically and, with the attachment of a central wheel, transported over Alpine terrain.

In 1948, Mariner led an international conference of rescue specialists in Tyrol to demonstrate these extraordinary creations. The conference laid the foundation for the International Commission on Alpine Rescue (ICAR), based in Switzerland, now the global association for the field. It set up Mariner for economic success in a Tyrolean industry that he helped develop (a classic “Alpha” personality, Mariner had great business acumen, and he was a master at preparing inventions for production). Finally, it produced two important works that would resurface in unexpected ways in America.

The first work was a documentary film showing off the technology that Mariner had sought to promulgate (the copy available here is a slightly revised and narrated cut made in 1998, with additional English subtitling later provided by Topograph Media):

As the film was shot by one of Lenni Riefenstahl’s cameramen, Otto Lantschner, it’s aesthetic power comes as no surprise. What couldn’t have been predicted is that a reel would soon be discovered in a bombed-out bookstore in Munich by a Bavarian émigré visiting his homeland after the war, Wolf Bauer. A mountaineer and environmentalist, Bauer brought the reel home and screened it to friends in Seattle, Washington. The deep impression it left would prompt them to form what, in time, became Seattle Mountain Rescue (SMR)—one of the most prominent search-and-rescue services in the country. Revealingly, even today SMR members refer to their newsletter as “Bergtrage,” a legacy of the name of an Austrian rescue stretcher known as a Gebirgstrage or a “Mariner Trage”:

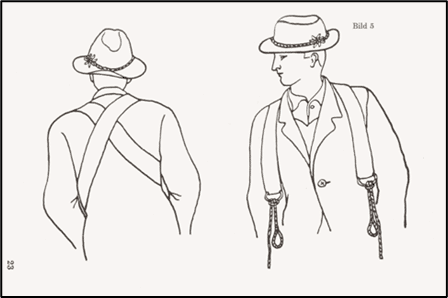

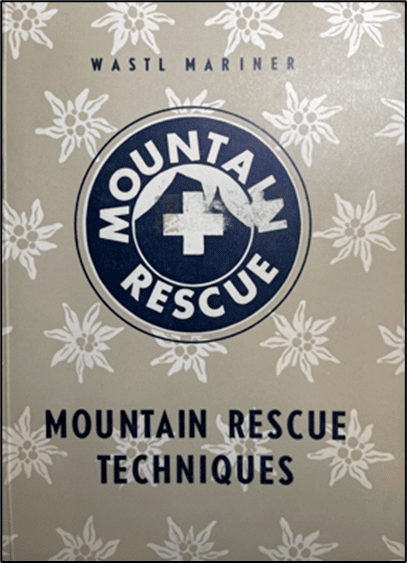

The second work to grow from the conference was Mariner’s classic how-to manual Neutzeitliche Bergrettungstechnik (1949), which was in essence a written summary of the techniques demonstrated at the gathering and teased in the film. Running about 180 pages, the book is divided into two sections, devoted respectively to techniques of summer and winter rescue; it includes an appendix on wilderness first aid, one of the first of its kind; and it features over 100 charming illustrations by Fritz Ebster, one of the great cartographers of modern Austria, and his brother Gerhard. The illustrations are an especially attractive feature of the book, as they depict rescuers in classic Alpine costume:

Additionally, the book contains prefatory essays by Mariner and Martin Busch, chair of the Alpine Association, that implicitly situate its aspirations within those of midcentury liberal internationalism—that is, as part of the same intellectual milieu that produced the United Nations (1945) and the World Health Organization (1948). As later Alpine Association chair Dr. Peter Grauss would write on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the 1948 gathering:

three years after the greatest catastrophe of this century, there was a lot more at stake than “just” talking about technical details of rescue and demonstrating new rescue devices. The yellowed 50-year-old documentary from our archives recalls to us that it was also about forging a new world. In the mountains, and in mountain rescue.

The goal of Mariner’s text was to help bring that new world into being through Austrian technical development and the standardization of mountain rescue practices across borders.

It would be difficult to overestimate the practical importance Neuzeitliche Bergrettungstechnik for search-and-rescue worldwide. As the pioneering American mountaineer Dr. Tom Hornbein explained to me in a recent video call, referring to the first, 1949 edition of Mariner’s text, “That book was our Bible, even though nobody could read it!” (few American mountaineers knew German, though the book’s illustrations often provided sufficient guidance).

Indeed, so great was the demand for Mariner’s book that multiple English renditions of it appeared in pirated form soon after its publication. Most notably, the esteemed American climber Allen Steck—who was a graduate student at UC Berekely and had been on his way to becoming a German language teacher before he turned pro—prepared a skilled, twenty-seven page partial translation that was widely distributed by the Sierra Club. Amusingly, the Sierra Club edition was itself the subject of further piracies. To undercut such well-meaning American copies, as well as to reach rescuers in Scandinavia and Holland (where it was not unreasonably assumed that an English text “would be preferred”), in the late 1950s the Alpine Association commissioned its own full translation from the author of a fine German-English technical pocket dictionary and business correspondence manual. Time would show that he was not an ideal choice given the subject matter.

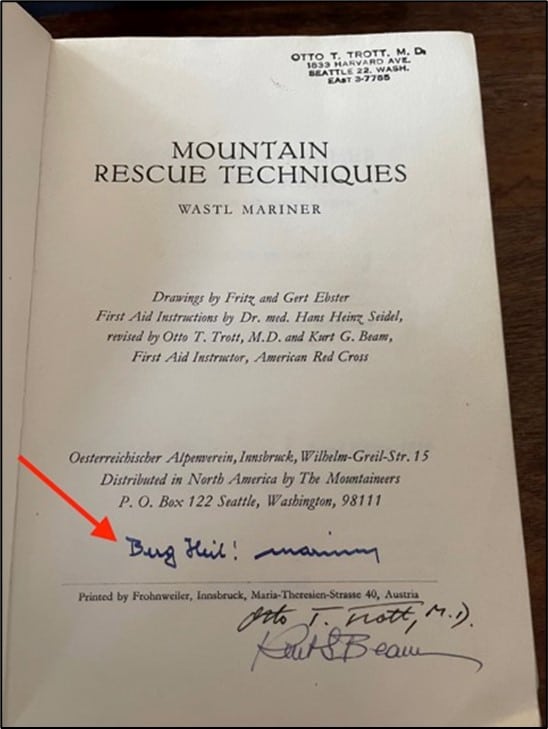

Shortly before the new translation went to press, the text found its way into the hands of a highly educated physician and mountaineer named Dr. Otto T. Trott. Classified as half-Jewish by the Nazis, Trott had fled to America in 1937 so that he could pursue his chosen profession. He soon moved to Seattle, where he became a member of the National Ski Patrol and Seattle Mountain Rescue. He was a man of high standards—including, as would soon become clear, when it came to translation work.

On October 23, 1961, Hans Kinzl, President of the Alpine Association, wrote Dr. Rudolf Campell, President of ICAR, revealing that he had heard from his colleague and that, despite the physician’s epistolary tact, his view of the translation had come through loud and clear. “[O]ur American friends have corrected the entire book and left it a slaughtered wasteland,” Kinzl explained. “I will speak today with the printer to see if we can clean it up.” But there was nothing to be done—there were too many errors to correct! Archival documents suggest that the original translator had produced a word-for-word translation, not a free rendering, and thereby lost the meaning of Mariner’s text as it would be used by rescuers in the field.

Trott agreed to produce a new translation, along with his colleague Kurt G. Beam, an engineer and outdoorsman from Vienna, of ethnic Jewish ancestry, who had fled to the United States after the Anschluss (he is shown below as a boy in Austria). Beam had also found his way to Seattle, and to National Ski Patrol and SMR, though the two rescuers were otherwise very different in outlook and experience. Trott’s father was a major Jewish art dealer. Beam’s father ran a successful textile business that especially manufactured cotton sponges used to clean locomotives. Trott was utterly devoted to the profession of medicine. A classic people person and a self-described family “black sheep,” Beam quit his engineering job at Boeing to become an insurance agent with State Farm so that he could spend more time skiing. Where Trott was tall, thin, and muscular, Beam had the frame of a bon vivant. The men did share a deep love of the mountains, and music, and Tyrol, but as collaborators, they were a bit of an unlikely pair.

As anyone who has engaged in a scholarly collaboration can appreciate, their work was thus not always easy. Family lore, on both sides, tells of many extended discussions about the translation, and sometimes heated arguments, around a long wooden table in Trott’s home, with Beam contentedly smoking a cigar at the end of the day (Trott was a non-smoker). The story of their work can be pieced together through papers scattered in multiple public, institutional and family archives. There are numerous heart-wrenching and dramatic moments to be savored in these documents, and humorous ones as well. For instance, as usual when it comes to writing and editing, expectations for speed regularly outstripped facts on the ground:

- July 1962, from a Seattle Mountain Rescue Council board meeting: “Otto Trott reported that progress was being made in the translation of the European Rescue Book and that it should be available by the end of the year.”

- April 1963, from another board meeting: “With any luck the book should be ready for distribution this summer.”

- July 1963: “Kurt Beam thinks the book should be out by November.”

- June 1963, a letter from Trott to Kinzl: “November is our yearly MRC meeting … We would be not only disappointed but greatly embarrassed if [the book] weren’t there in time.”

- August 22, 1963, Beam to Kinzl: “Seen from our end, the prospects for the book look excellent. … It is now up to you and your good associates to do your part to get the rough draft of this book without delay.”

- August 23, 1963, Trott to Kinzl: “It would be an international disaster if the book weren’t ready for the 9-10 November conference.”

- October 11, 1963, Kinzl to Trott: “You cannot expect us to get you the book for your 9-10 November conference.”

- October 18: Trott to Kinzl, explaining that the galleys arrived immediately after he had finished delivering a baby, “please please please make sure that Campell gets 10 or more copies [to bring to the conference].”

- October 19, Beam to Kinzl: “we have been up all night, and the corrections are done.”

The first copies of Mountain Rescue Techniques became available in the United States in July 1964.

Fittingly, the volumes to be sold in America had a revised cover. They now featured not the Alpine Association’s Medal of Honor (an edelweiss flower upon a green cross with the letters A and V in the tips of two yellow stamens), but rather the logo of Seattle Mountain Rescue, a silhouette of Washington’s Mt. Baker. For Trott and Beam, the change came as a delightful surprise—it had been made on the initiative of the Alpine Association in a token of respect and esteem. The logo itself had in fact been designed by Trott, who once described Mt. Baker as having provided “complete compensation for the loss of skiing in my beloved Alps, which I had thought to be irreplaceable.”

By 1967, orders for the book—which was adopted, in English, as ICAR’s “official manual”—had come from nearly every state in the Union, including Alaska and Hawaii, most provinces of Canada, and from across the world, including India, Rhodesia, Kenya, Hong Kong, and Ecuador, England, Australia, and New Zealand. The book included a fine, free translation of Mariner’s original text, made by two specialists who understood its prose from the perspective of rescue in the field. In addition, it included a list of active mountain rescue associations in North America; a current bibliography; and a substantially updated and revised appendix for mountain medical practice—the proud work especially of Dr. Trott.

Mariner, for one, was pleased:

There’s much more one could say about Mountain Rescue Techniques and the cast of characters who made it possible, but that will have to wait for another forum. Still, there’s one aspect of this story of Austrian-American technical arbitrage and exchange that should be mentioned in closing—namely, that it would continue. In the mid-twentieth century, Austrian technology and know-how developed during World War II flowed to the United States. Today, a number of rescue practices developed by the American military under its Tactical Combat Care program are influencing Austrian mountain practice under the banner of Tactical Alpine Medicine. Indeed, if you ever have the chance to attend an Austrian mountain rescue training course, you’ll find that many of the medical terms and even mnemonics used are English.

It’s a fascinating development—about which, as they say in my hometown of Los Angeles, “go see the movie!”

—

If you’d like to learn more about the ideas behind my film, you can tune into a podcast that I recorded last year with the Hamburg branch of Scientists4Future. You can also read an essay about Emergency Medical Services that I wrote for the social philosophy journal Telos (the link leads to a summary on my blog; the full article in the journal is available online through academic libraries). And by the way, here I am recently “hard at work” on the project in Ramsau am Dachstein, the setting for the hit ZDF television series “Die Bergretter”: