A Habsburg Archduke in Hollywood!

By Jacqueline Vansant

If I were to ask you which Hollywood film you associate most with Austria, you’d probably say The Sound of Music without much hesitation. Yet, it is only one of over fifty films made in Hollywood that were set in Austria. And if I were to ask you to name some Austrians who worked or are working in the film capital, you might think of Arnold Schwarzenegger or Christoph Waltz or possibly such Hollywood directors as Erich von Stroheim, Josef von Sternberg, or Billy Wilder. I doubt if anyone would name Archduke Leopold of Austria. However, in the same decade that Erich von Stroheim, the Austrian-born director with a self-endowed aristocratic title, introduced Emperor Franz Josef to the Hollywood screen in Merry-Go-Round (1923), a great-grand-nephew of the Austrian emperor, Archduke Leopold of Austria, spent time in Hollywood and even appeared in at least two films. I discovered this as I was researching Stroheim and sifting through issues of Photoplay, one of the first film fan magazines. Blurry eyed from staring at microfilm, I stumbled across two articles from 1928 there by the Austrian archduke. Although the articles intrigued me at the time, I had to set them aside. Yet, questions about this Habsburg in Hollywood persisted. Who was this Austrian archduke? What was he doing in Hollywood? What were his impressions?

To find the most basic information on the archduke’s time in Hollywood I turned to the International Movie Database (IMDb), which notes that he “is known for his work on Four Sons (1928) and Night Life (1927).” In addition to this, IMDB lists him both as an uncredited actor in and an uncredited technical advisor for Stroheim’s The Wedding March. Next I took advantage of the fan and industry publications available on-line via the Media History Digital Library to see what I could turn up on Leopold. Between 1927 and 1930, “Archduke Leopold of Austria” was referenced in Exhibitors Herald and Moving Picture World, Variety, Motion Picture News, Picture Play and Photoplay, film industry and fan magazines numerous times.

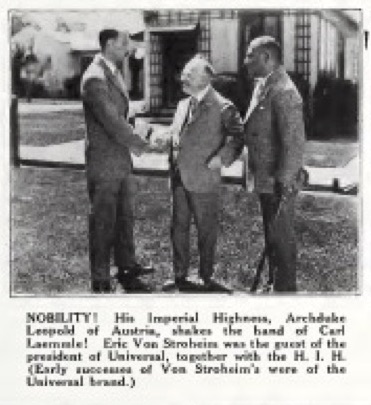

The articles and short blurbs with references to the archduke tell numerous stories. First and foremost, they reveal both the fascination and the mild disdain Americans had for European aristocracy. While the Motion Picture News from June 3, 1927, announce that the archduke is in Los Angeles as part of “a pleasure trip,” according to Leopold in the June 1928 Photoplay article he had received an invitation to Hollywood from Erich von Stroheim’s publicity manager “to inspect Stroheim’s new picture ‘The Wedding March.’” Whatever brought the former royal to the film capital, he might have thought that his name and (defunct) title would open doors for him there, for it seemed to have for Erich von Stroheim, who was not really royalty. At the same time, it appears that Hollywood sought to benefit from the visit. Within a week of each other, the Exhibitors Herald on May 28, 1927, and Motion Picture News on June 3, 1927, introduce the visitor with much pomp as “Archduke Leopold of Austria, grandnephew of Emperor Franz Josef I, and cousin of the late Emperor Charles.” A few months later in the September 1927 issue of Picture Play magazine, the article entitled “An Archduke in Hollywood” pronounces that “Hollywood just must have its royalty” (73). It goes on to introduce Archduke Leopold of Austria, stating “he would have been one of the direct heirs to the throne had it not been for the upheavals that have taken place in his native country.”

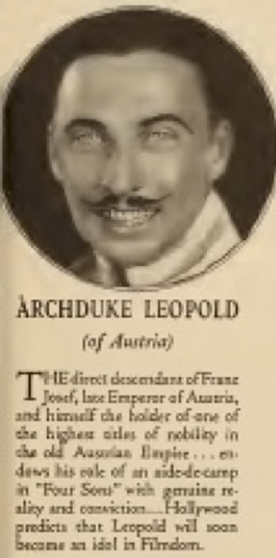

Although it is not possible to determine whether Leopold or the Hollywood publications inflated his connection to more famous Habsburgs—as he was at best a great-grandnephew of the old emperor and certainly not a direct heir—that a Habsburg in Hollywood was newsworthy for the movie-going public was clear. Publicity agents for John Ford’s Four Sons sought to capitalize on both his title and his foreign roots in advertisements for the film. In a two-page spread in Exhibitors Herald and Moving Picture World from March 31, 1928, with the heading “The Genius of All Nations is Combined in Four Sons Big as the Heart of Humanity,” a photograph of the archduke was included along with other actors with foreign roots and the text: “The direct descendant of Franz Josef, late Emperor of Austria, and himself the holder of one of the highest titles of nobility in the old Austrian Empire … endows his role of an aide-de-camp in ‘Four Sons’ with genuine reality and conviction … Hollywood predicts that Leopold will soon become an idol in Filmdom.” The ad suggests that the use of European actors and particularly a titled one lends the film authenticity.

While the draw of royalty was undeniable, another article playfully entitled “Fallen Archdukes” in Exhibitors’ Herald from August 13, 1927, spoofs the spectacle the archduke’s appearance on the film set provoked in the behavior of “former members of the Austrian nobility and military forces.” When Leopold passes they “invariably snap their heals together and salute. They remain in that position until he returns their respectful greeting, and then they go on about their business” (10). The author points to one poor soul overlooked by the archduke, who stood at attention for ten minutes until the archduke returned to dismiss him. According to the article, the archduke displays more democratic qualities than his Austrian compatriots. Despite the fact that “Leopold tries to impress it upon his countrymen that he’s plain Mr. Man, they insist on treating him ‘royally.’”

Indeed, the cachet of his title opened doors for the archduke and perhaps led to his being cast in minor roles in Hollywood. However, if he were hoping for greater fame, this did not pan out. The archduke registers his disillusionment with Hollywood in the two Photoplay articles from May and June of 1928. In “A Habsburg Sees Hollywood. The Capital of Motion Pictures Is Viewed by an Observing Royal Extra,” he writes of the precarious position of most workers and states that “Hollywood is a Fata Morgana—a mirage—which lures thousands to walk its streets, although only a very few reach the lucky oasis” (92). In the follow-up article “Sketches from Hollywood. Some impressions, political and personal, of a visiting Habsburg,” he disparages the lack of education of 90% of those working in the studios. Perhaps disappointed that von Stroheim did not make a film with him cast as the ill-fated Maximilian I, Archduke of Austria and Emperor of Mexico, as reported in both fan and industry publications, he takes a jab at his fellow Austrian. Implying that it wasn’t Eric von Stroheim’s talent that paved his way in Hollywood, he claims that “Eric von Stroheim proved that anyone who takes a good picture can be a movie actor.” He also derides Hollywood’s disregard for authenticity in his anecdote about a set designed to replicate Vienna by a former German attaché who had never even visited the Imperial City. Although it was more Italian than Viennese, it was good enough for the director.

Leopold’s time in Hollywood was short-lived. His obituary in the New York Times, which appeared on March 15, 1958, with the headline “Leopold Habsburg Lorraine Dead at 61; Austrian Archduke Became U.S. Citizen,” mentions it in one brief line: “He came to the United States in 1927 and became a motion-picture ‘bit’ player in Hollywood.” Not an uncontroversial Habsburg, he was accused and cleared of a charge of grand larceny in 1930. At some point after his stint in Hollywood he moved to Willimantic, Connecticut where he was a factory worker. With its ups and downs, his life story has all the makings of a Hollywood drama.

Author Biography:

Jacqueline Vansant, Professor of German at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, has written widely in German and English on the topic of images of Austria in Hollywood. Her book Austria, Made in Hollywood (Rochester: Camden House, 2019) and the article “Austrian and Dust Bowl Refugees Unite in Three Faces West.” Journal of Austrian-American History, Vol, 1, No. 1 (2017): 98-116, both benefited from the support of a BIAAS grant in 2010. Other articles related to the topic include “Political and Humanitarian Messages in a Horse’s Tale: MGM’s Florian,” Austrian History Yearbook 42 (2011): 164-184 and “Hollywoods ’Wien’ als transnationaler Gedächtnisort.“ Jenseits von Grenzen. Transnationales, translokales Gedächtnis. (Vienna: Präsens Verlag, 2007), 183-196.

Relevant Links:

International Movie Database

List of Heirs to the Austrian Throne

Media History Digital Library

Suggested Reading:

Gemünden, Gerd. Continental Strangers: German Exile Cinema 1933-1951. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

Horak, Jan-Christopher. “Sauerkraut and Sausages with a Little Goulash: Germans in Hollywood, 1927.” Film History 17, no. 2 (2005): 241-60.

Horwath, Alexander and Michael Omasta, eds. Josef von Sternberg: The Case of Lena Smith. Vienna: Österreichisches Filmmuseum/Synema, 2007.

Judson, Pieter (BIAAS Board Member). The Habsburg Empire. A New History. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016.

Kosarski, Richard. VON. The Life and Films of Erich von Stroheim. New York: Lifetime Editions, 2001. Original edition published by Oxford University Press under the title The Man You Love to Hate, 1983.

Ulrich, Rudolf. Österreicher in Hollywood. Vienna: Verlag Filmarchiv Austria, 2004.

Suggested Viewing:

Four Sons. John Ford. Twentieth Century Fox, 1928.

Merry-Go-Round. Erich von Stroheim/Rupert Julian. Universal, 1923.

The Wedding March. Erich von Stroheim. Paramount Pictures, 1928.

Image:

June 18, 1927 in the Exhibitors Herald and Moving Picture World (27)