Zinzendorf and Zinner: Two Unlikely Experts on the American Revolution

By Jonathan Singerton

Before the American Revolution had even begun, the British ambassador in Vienna disgruntledly commented to his superiors in London, “every idle fellow talks of America.”[1] Yet who really knew what they were talking about, exactly? Who in the Habsburg Monarchy knew the most about the faraway land across the Atlantic Ocean?

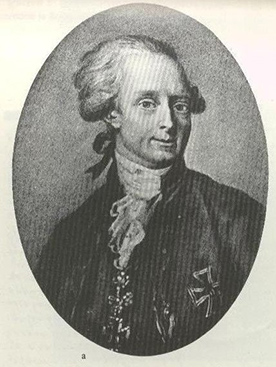

Of all Habsburg subjects, one of the most learned was Count Karl von Zinzendorf. A Saxon by birth but scion of an ancient Austrian family, Zinzendorf studied in Jena before he joined the Austrian bureaucracy in the 1760s. From Vienna, he embarked upon a series of commercial tours of Europe as a means to gather intelligence on the latest economic and administrative ideas. Great Britain naturally featured among his destinations and it is there he gained his first recorded knowledge of America.

In a report prepared specially for the Austrian government, Zinzendorf devoted an entire section to the economic and legal arrangements in British North America. Spanning nearly one hundred pages, Zinzendorf described how the colonial government operated in all twenty-six colonies (on the North American mainland and in the Caribbean), listed their major manufactured goods, detailed the types of currencies circulating, explained property rights, calculated the populations of each colony and their tax incomes, and provided a history of each major city from Boston to Philadelphia, New York to Charleston.[2] Zinzendorf’s thorough work was the most accurate assessment of colonial America available in the Habsburg Monarchy.

Zinzendorf continued his fascination for North America throughout his life. On the eve of Revolution, Zinzendorf’s interests spiked as he asked around the Viennese court for news from America.[3] In 1776 he was made Governor of Trieste, where he frequently discussed the “troubles of Boston” over dinners with foreign consuls.[4] Zinzendorf’s position in the most vibrant port of the Habsburg Monarchy also allowed him unfettered access to materials coming directly from the self-declared United States of America. In 1778, for instance, he read Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, John Dickinson’s Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, and the British radical Richard Price’s Observations on the Nature of Civil Liberty, the Principles of Government and the Justice and Policy of the War with America.[5] At the end of that year, his new map of America arrived.[6]

In the mid-1780s, Zinzendorf was still reading Americana such as William Robertson’s History of America and borrowed essays on the American Revolution from Franklin’s closest friend in Vienna, Dr. Jan Ingenhousz.[7] When the French Revolution broke out, Zinzendorf was among the few in the Habsburg Monarchy to recognize the parallels between 1776 and 1789, noting in his diary that New York and Paris were “the only two places on this globe, where interesting things happen for humanity.”[8]

Zinzendorf was a courtier through and through; except for his interlude in Trieste and sojourn across Europe in the 1760s, he spent the majority of his life in the Habsburg capital and serving in various positions at court. His personal interest in the American Revolution shows us even courtiers who were close to the imperial regime and who we might assume to be conservatively minded—and therefore naturally against Revolution—were instead avidly interested in the American Revolution. Zinzendorf is an example of how interested courtiers also spread news of the Revolution through sharing works by written by patriot Americans.

The desire to share knowledge of the American Revolution did not just affect courtiers, however. One of the most interested observers of the American Revolution in the Habsburg Monarchy lived in Košice (at that time also referred to as Kaschau and Kassa). Nestled on the eastern side of the Tatra Mountains, far removed from the Habsburg capital, the city boasted a prestigious Royal Academy in the eighteenth century. Johann Baptist Zinner worked at this institution as the Professor for Universal History from the 1770s until 1790s. During this time he became fascinated by the American Revolution, reading whatever news he could glean about the conflict from the international sections in liberal newspapers from the Dutch Republic and Poland.

These sources, however, sometimes proved to provide competing accounts or contradictory facts. Zinner addressed this problem in his first letter to Franklin in 1778. The famous turncoat Benedict Arnold, Zinner complained with some exaggeration, “is sometimes made a German of Mainz, sometimes an American of Connecticut, sometimes a lapsed Capuchin monk, and sometimes a grocer of Norway.”[9] How was he to know the truth? Zinner’s dilemma was all the more urgent since he was currently at work on two books on the American Revolution and, as a good historian, needed to know fact from fiction.

Zinner travelled to Paris to visit Benjamin Franklin and find out the facts about the American Revolution.[10] Thanks to Franklin’s assistance, Zinner completed not two but three manuscripts on the history of the American Revolution. His first book appeared in print in 1782, entitled Merkwürdige Briefe und Schriften der berühmtesten Generale in Amerika, which, apart from providing nearly sixty actual letters and sources, included biographies of numerous American and British revolutionary leaders.[11]

Zinner’s following two works were not published but must have been used by his students in Košice. Zinner completed his Notitia Historica de Coloniis Americae Septentrionalis in 1783, which provided a statistical overview and summary of the War of American Independence over 150 pages in three parts.[12] Both this and his published book paled in size compared to his Versuch einer Kriegsgeschichte der verbündenen Staaten von Nordamerika, handwritten in 1784. It recounted the entirety of the American Revolution, starting from the discovery of America and ending with the post-war economy of the new United States across 106 chapters and nearly 550 pages.[13] Zinner’s account predated David Ramsay’s well-known The History of the American Revolution by five years and Mercy Otis Warren’s History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution by twenty-one years.[14]

Zinner’s extraordinary undertaking, although unfortunately unpublished, means one of the most detailed and longest contemporary accounts of the American Revolution was written by a Bohemian-born professor in a German-, Slovak-, and Hungarian-speaking city in a relatively remote corner of Habsburg Monarchy. His detailed knowledge—amassed from cross-checked newspapers and writings provided by Franklin—make him the undoubted but historically forgotten expert on the American Revolution in the Habsburg Monarchy.

Author Biography:

Jonathan Singerton is a specialist on the early connections between the Habsburg Monarchy and North America. He recently completed his PhD entitled ‘Empires on the Edge – The Habsburg Monarchy and the American Revolution 1763-1789’ at the University of Edinburgh. He is currently a Plaschka Fellow at the Institute for Modern and Contemporary History at the Austria Academy of Sciences, Vienna.

Notes:

[1] Sir Robert Murray Keith to Mr. Bradshaw, 15th September 1774 in Gillespie Symth, Memoirs and Correspondence of Sir Robert Murray Keith (London, 1849), I, 474-482.

[2] Haus-, Hof-, und Staatsarchiv [HHStA], Staatskanzlei, England, Varia, K. 11, ‘Observations,’ ‘Colonies Angloises dans l’Amérique Septentrionale et dans l’Archipel des Antilles,’ fols. 639-733.

[3] “Je cousais avec Ingenhousz sur les Colonies. Il m’explique l’origine des querelles” in HHStA, Sonderbestände, Nachlass Zinzendorf, Tagebuch Zinzendorfs, Band 20, entry dated 3rd October 1775, fol. 131; ibid., Band 21, entry dated 31st January 1776, fol. 16r.

[4] Entry dated 30th July 1776 in Grete Klingenstein et al, eds., Europäische Aufklärung zwischen Wien und Triest – Die Tagebücher des Gouverneurs Karl Graf Zinzendorf 1776-1782 (Vienna: Böhlau Verlag, 2009), II, 40; 1st January 1777 in ibid., II, 125; 25th June 1779 in ibid., III, 448.

[5] HHStA, SB, NZ, TZ, Band 23, entry dated 16th May 1778: “Je lus un instant dans le pamphlet américain Common Sense qui [étoit] fait pour attirer le feu contre le roi d’Angleterre.”; ibid., entry dated 30th May 1778 : “Commencé les Letters of a Farmer “ on 30th May 1778; Klingenstein et al, eds., Europäische Aufklärung zwischen Wien und Triest, II, 155, entry dated 9th March 1778: “Chez moi, je lus avec plaisir la brochure du Dr Price sur la valeur morale *et politique* de la guerre avec l’Amérique. Il est hardi mais bien profound.”

[6] Ibid., II, 311, entry dated 2nd December 1778: “Hier j’ai reçus mes cartes de l’Amérique que j’attendois depuis si longtemps.”

[7] HHStA, SB, NZ, TZ, Band 30, entries dated 15th January 1785, fol. 8 and 5th October 1785, fol. 178.

[8] HHStA, SB, NZ, TZ, Band 34, entry dated 11th July 1789: “Les deux seuls cours de ce globe, ou il arrive des choeses intéressantes pour l’humanité.”

[9] “particulierment de Mons. Arnold: on le fait tantot un Allemand de Maienz, tantot un Ameriquain de Connecticut, tantot un Capucin cidevant, tantot un epicier de Norvich” Zinnern to Franklin, 26th October 1778 in American Philosophical Society, Ms.BF.85, V.

[10] “…der Herr Verfasser gleichsam bey der Quelle selbst geschöpfet und gesammelt hat, da er bey seinem Aufenthalte in Paris die Ehre genossen hat, mit dem Herrn D. Franklin genauer bekannt zu sein, und von ihm und durch seinen gütigen Vorschub vieles zusammen zu bringen…” in Johann Zinner, Merkwürdige Briefe und Schriften der berühmtesten generäle in Amerika (Augusburg, 1782), 4-5.

[11] Johann Zinner, Merkwürdige Briefe und Schriften der berühmtesten Generale in Amerika nebst derselben beygefügten Lebensbeschreibungen (Augsburg, 1782).

[12] Johann Zinner, Notitia Historica de Coloniis Americae Septentrionalis (Košice, 1783) in Verejná Knižnica Jána Bocatia v Košiciach (Public Library of Jan Bocatius of Košice), Rukopisné diela Jána Zinnera.

[13] Johann Zinner, Versuch einer Kriegsgeschichte der verbündenen Staaten von Nordamerika (Košice, 1784) in Verejná Knižnica Jána Bocatia v Košiciach (Public Library of Jan Bocatius of Košice), Rukopisné diela Jána Zinnera.

[14] David Ramsay, The History of the American Revolution, Vols. 1-2 (Philadelphia, 1789); Mercy Otis Warren, History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution, Vols. 1-2 (Boston, 1805).

Further Reading:

Gernot O. Gürtler, “Impressionen einer Reise: Das England-Itineraire des Grafen Karl von Zinzendorf 1768,” Mitteilungen des Instituts für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung, 93/3-4 (1985), 333-370.

Grete Klingenstein, Eva Faber, and Antonio Trampus, eds., Europäische Aufklärung zwischen Wien und Triest – Die Tagebücher des Gouverneurs Karl Graf Zinzendorf 1776-1782, Vols. I-IV (Vienna: Böhlau Verlag, 2009).

Robert Rill, Die Reise des Grafen Karl von Zinzendorf und Pottendorf über die britischen Inseln im Jahre 1768 am Hand seiner Tagebuchaufzeichnungen, (Unpublished Thesis: University of Vienna, 1983).

Jonathan Singerton, ““Some of Distinction Here Are Warm for the Part of America”: Knowledge of and Sympathy for the American Cuase in the Habsburg Monarchy, 1763-1783,” Journal of Austrian-American History, Vol. 1, No. 2 (2017), 128-158.

Peter Winter, “Johann Carl Zinner,” Mesto a dejiny, Vol. 2 (2015), 55-61.

Géza Závodszky, “Zinner János, az angol alkotmány elsö hazai imerteöje”, Magyar Könyvsszemle, 103 (1987), 10-18.

Archival Sources:

Haus-, Hof-, und Staatsarchiv, Staatskanzlei, England, Varia, K. 11, ‘Observations’ by Karl von Zinzendorf, ‘Colonies Angloises dans l’Amérique Septentrionale et dans l’Archipel des Antilles,’ fols. 639-733.

Verejná Knižnica Jána Bocatia v Košiciach (Public Library of Jan Bocatius of Košice), Rukopisné diela Jána Zinnera, Johann Zinner, Notitia Historica de Coloniis Americae Septentrionalis (Košice, 1783) and Johann Zinner, Versuch einer Kriegsgeschichte der verbündenen Staaten von Nordamerika (Košice, 1784).

Further Links:

Johann Zinner, Merkwürdige Briefe und Schriften der berühmtesten Generale in Amerika nebst derselben beygefügten Lebensbeschreibungen (Augsburg, 1782): https://books.google.de/books?id=2Dk9AAAAYAAJ&pg=PP5&lpg=PP5&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false

David Ramsay, The History of the American Revolution, vol. 1 [1789]

https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/ramsay-the-history-of-the-american-revolution-vol-1

Mercy Otis Warren, Historian of the American Revolution: https://www.historyisfun.org/blog/mercy-otis-warren/

Jan Ingenhousz as the discoverer of photosynthesis: https://www.forbes.com/sites/kionasmith/2017/12/08/todays-google-doodle-honors-jan-ingenhousz-and-the-discovery-of-photosynthesis/