Wide Awake and Worlds Away: Percy Lavon Julian’s Scientific Education in Vienna

By Kristina E. Poznan

“Truly I was the luckiest guy in all the world to land here [in Vienna]. For the first time in my life I represent a creative, alive, and wide-awake chemist.”

– Percy L. Julian to Robert Thompson, December 1929 (Afro American, July 30, 1932)

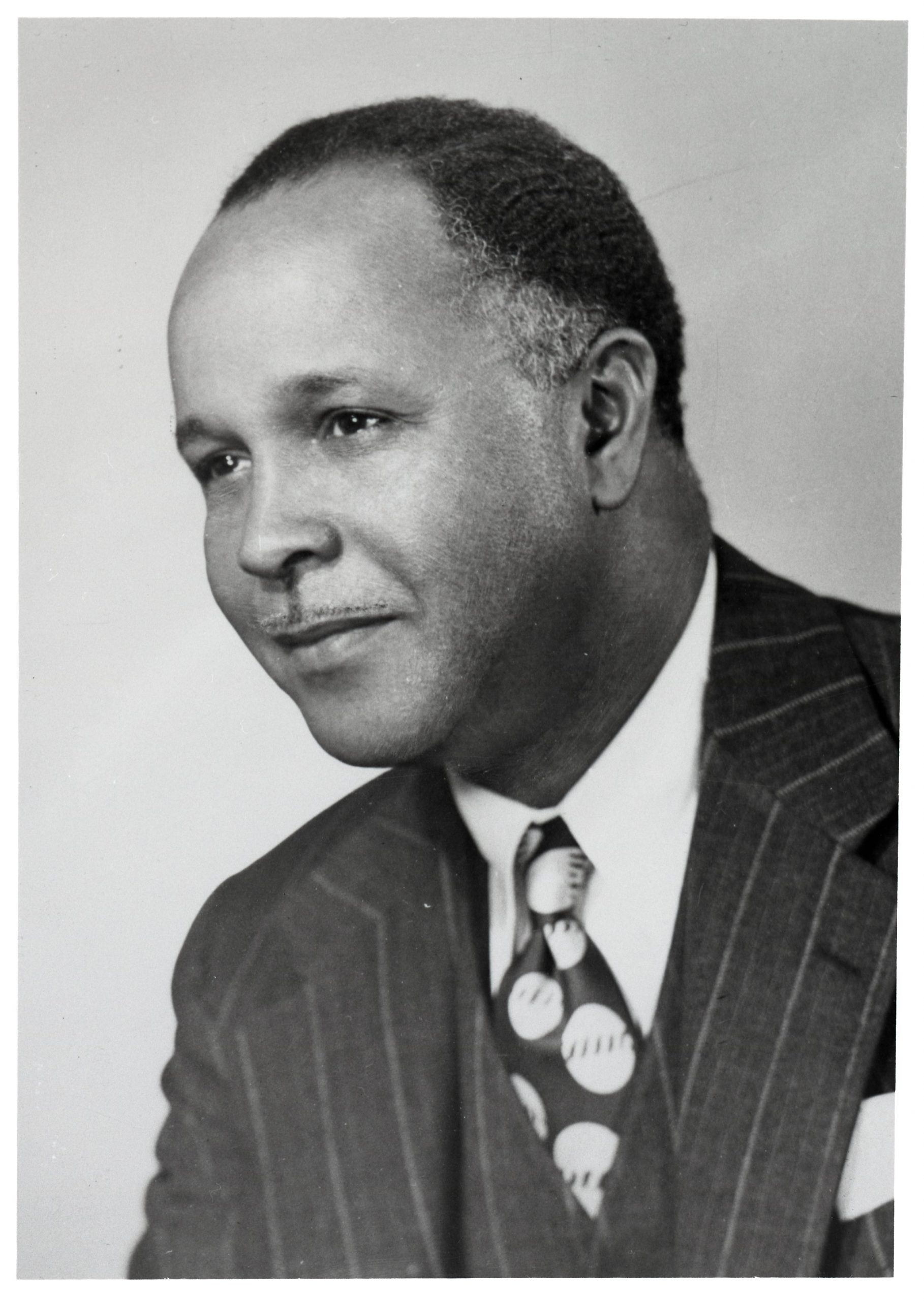

Percy Lavon Julian became the third African American to earn a Ph.D. in Chemistry when the University of Vienna awarded him his doctorate in 1931. Julian had been born in Alabama and educated at the Lincoln Normal School, DePauw University, and Harvard University. He subsequently taught at Fisk University, West Virginia State College, and Howard University, educating a host of black students in chemistry. While teaching at Howard, Julian earned a Rockefeller Foundation scholarship that enabled him to go to Vienna to complete his studies under Dr. Ernst Späth.[1] The Austrian stamp on Julian’s training and early findings with Universtät Wien classmate Josef Pikl are known and prominently discussed in the NOVA documentary Percy Julian: Forgotten Genius.

But Julian’s admirers tread carefully discussing his time in Austria, which we know about mostly from letters that he wrote to colleagues back in the United States, particularly Robert Thompson. A workplace dispute at Howard University, where Julian returned to teaching after earning his PhD, bound up with the affair between Julian and Thompson’s wife, sociologist Anna Johnson, spilled into the press. The Baltimore Afro-American published Julian’s private letters to Thompson, making public his commentary about university figures and student life in Austria that was very much intended to be private. The blowback against the leaked letters eventually forced Julian to resign from the faculty at Howard and retreat to the laboratories at his alma mater, De Pauw. The Afro-American newspaper did Julian a tremendous disservice in publishing his Austrian letters in the summer of 1932, but the publication of those very same letters gives us a fascinating look into Julian’s time abroad.

Julian’s path to Vienna for doctoral studies was long and circuitous, but his two years there were phenomenal, both academically and socially. Taking up residence at Liechtensteinstraße 45A, a fifteen-minute walk north of the university, he delighted in “work and play!” with “jolly good companions” and the “exciting current of new scenery and new everything.”[2] Julian’s skin color was more of a novelty than a barrier at the university and in the social circles of his classmates, opening up opportunities for him in Austria that had been inaccessible in Jim Crow America. Julian, aged 30, jubilantly wrote to Thompson, “I am ten years younger. It is many a year since I have been so happy and healthy. I eat like dog . . . and sleep like Rip Van Winkle.”[3] Vienna did him good; Julian flourished personally and scientifically.

Julian’s letters reveal his assessment of the differences in the study of chemistry on both continents. “German chemistry is all that it has been said to be,” he confirmed, though “the system in this damned laboratory is about to run me crazy. . . . You are issued equipment that is not half as good as our Chemistry 125 equipment”! As he visited the glass shop so often, he quipped, “I certainly will know the German name for every different kind of apparatus.” Setting up for his experiments, Julian needed Thompson to send him a box (or two or three), requesting, among other things, a stirring motor, platinum foil and wire, clamps, rubber stoppers, corks, silver nitrate, vacuum tubing, an electric water bath, and a supply of emetine. The cost of chemicals in Vienna was particularly galling. But other instruments available in Vienna were superior to their American counterparts, however costly. “They make the best water suction pumps here (of glass) that I have ever seen,” he remarked, praising also the balances.[4] The scientific benefits of international educational exchange were playing out in Späth’s lab, and would continue in the labs that Julian would subsequently set up back home.

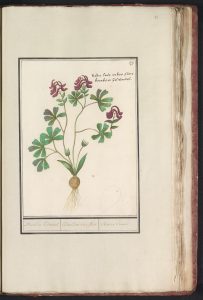

Julian’s studies in Vienna focused on isolating alkaloids, nitrogen-containing plant chemicals. Caffeine, morphine, and other chemicals we use as drugs are isolated plant alkaloids or synthesized versions of them. “Synthetic chemists are more artists than other types of scientists,” explains biochemist Gregory Petsko.[5] At Späth’s lab, Julian studied several plants, including opium and Corydalis cava, sometimes called hollowroot, a woodland plant with white, purple, and pink flowers, native to Central Europe, containing painkilling alkaloids. Having finally made a breakthrough nearly a year into his work, Julian blew off a trip to the Bavarian Alps to finish synthesizing alkaloids instead. “I stick here and Oberammergau can go to Hell,” he wrote; Europeans considered it a destination only for tourists, anyhow, he told Thompson.[6] Though he enjoyed the diversions Vienna’s environs offered, Julian’s focus remained fixed on his opportunities to learn and work.

Doctoral studies could be much briefer then than now, but there was “only work for little Percy.” Julian logged tremendous numbers of hours in the lab in his two years there. “The professor told me today I worked too feverishly,” he confided to Thompson, “and he wanted me to feel that I could take time out and go and have a drink with the fellows in our ten-hour day.” His many books lay sprawled in his room “like a cyclone.” Mixed in the chaos were his notes, “in preparation for my Doctor’s exams – scattered pages of my Dissertation, which is that damndest job that mortal can undertake.” He declared, “Dass ist die gewohnlicher Geschichte bei der Chemie!”[7] Thus, he affirmed his devotion to the painful labors of chemical discovery.

Julian’s time in Austria was dominated by his studies, but supplemented by Viennese social life, magnificent in and of itself but even more liberating outside the confines of Jim Crow. “I have more invitations to fellow companion’s houses than I can accept,” he declared. “Viennese are known for their hospitality, or what they call “Gemuetlicheit.”[8] The enduring virtues of the city had their impression on him: the opera (“Boy, it was music”), cuisine (“you never saw sandwiches until you come to Germany of Austria),” wine (“a wonderful six-fifths of the Champagne for about three dollars. . . Bordeaux, which of course was dirt cheap”), Viennese women (“a beauty indescribable”).[9] On a particularly memorable night, he went on a date with a classmate’s sister to an “entrancingly beautiful” performance of Beethoven’s “Fidelio,” followed by a drink at “the sweetest little wine cellar.”[10] Such details of dating and implications of sex were explosive once published two years later, but at the time, it was life lived to the fullest. Julian frequently joined the cosmopolitan family of Edwin Mossettig on outings outside of school: visiting the opera, skiing, and swimming in the Danube.[11] Vienna was his ticket to further study, new forms of leisure, and a respite from Jim Crow. “The freedom of European Life” Julian basked, “with its calm recognition of Duty, Honor, and necessity—and its absolute denial of the prude or puritanic—is the one joy forever.”[12]

Julian’s struggles with German as an international student will be familiar to many Americans who have learned the German language. “Very often I wonder why I’m so weary and then the realization comes that its this searching after words and keeping straight this damned subjunctive mode,” he mused, equating likening for vocabulary to “digging up words from a labyrinth.” Preparing for a colloquium, Julian fretted over “that inevitable fear that I will say ‘Das Valenz’ rather than “die Valenz.’ Why in Hell valence should be feminine I can’t see unless some damned German wanted to have a good joke,” he grumbled.[13] But writing Thompson a year later, he boasted that in his pre-doctorate lecture he “made only one mistake” in German, needlessly adding “-atom” to the end of “der Kohlenstaff,” carbon.[14] Julian’s long hours in the lab had paid off, and he was now working on preparations for graduation and publications.

Julian relished the recognition of his accomplishments, in sharp contrast to the devaluing of black excellence at home. “If I may indulge in a bit of bragging. . . .The professor thinks I’m a jewel, and so my day is here!!!!”[15] Julian’s “pre-Doctorat” speech was, in his words, “the public climax.” His presentation was well attended: “All the Professor, Dozents, and Assistants were in the first rows. Many of my Vienna friends were in the audience.” Also present were two African American students studying medicine in Vienna, who “sat there with eyes as big as apples. The news will find its way back to black America,” Julian predicted.[16] Prof. Späth described Julian as “Ein ausserordentlicher Student wie ich in meiner Laufbahn noch nie gehabt habe,” “an extraordinary student, the likes of which I have never had before in my career as a teacher.”[17] Surely if Julian had proven he was the best’s among Späth’s students, he had been good enough all along for Harvard, and to have his way at Howard. “Strange, one is appreciated everywhere more than among his own,” he reflected sadly.[18]

Julian was not alone among African Americans in pursuing educational or academic opportunities in Europe instead of in the United States and finding a more accepting academic climate there. W. E. B. Du Bois, for example, had engaged in graduate studies at the University of Berlin. Julian wrote to Du Bois from “Karlsbad in Tschechoslowakei” in August 1931, after he had defended his dissertation. He explained the circumstances that had driven him from Harvard, where he had earned his Master’s and wanted to continue with his doctorate, but could not once the customary teaching assistantships that bankrolled such an endeavor were retracted. Summing his Vienna experience to Du Bois, Julian wrote, “I have had the pleasure (and pain?) of contact with all phases of Austrian life – the Jewish students who are beaten with clubs periodically at the University, . . . the poor students who eat for 25¢ a day and happily do their work, the wealthy who sigh over good old days gone by, with Hungarians who curse Roumania, Austrians who hate Prussians and who laugh at American Intellect, yet bow before American money, and the Viennese whose humaneness is not to be found very often in any part of the world.”[19] Julian, bracing himself to return to the United States, proved himself an astute observer of the troubles in Austrian society, despite having overwhelmingly enjoyed the pleasures of Viennese life during his studies.

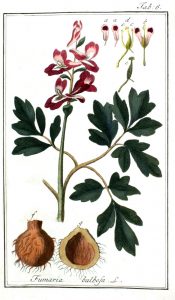

Julian’s return to DePauw in 1932 after the debacle at Howard was not exactly voluntary, but he would not have to go alone. His fellow University of Vienna chemistry classmate, Josef Pikl, an invaluable partner in the laboratory, would join him. Together they threw themselves into isolating alkaloids from natural products and then producing them synthetically, publishing no fewer than eleven articles in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, with Julian as the lead author, Pikl as the second author, and many of them with student co-authors.[20] Much of their research came from isolating alkaloids from purple Calabar beans from Africa.[21] Among their most significant breakthroughs was correctly synthesizing physostigmine in a dramatic race with chemist Robert Robinson.

Julian and Pikl’s findings brought no shortage of scientific attention to DePauw, but the university offered him no permanent position; by 1936, the duo went looking for jobs in industry. When Wilmington-based E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company invited Julian and Pikl to interview, DuPont offered Pikl a job but explained to Julian, “We didn’t know you were a Negro.” Julian’s job offer with the Institute of Paper Chemistry fell through with the realization that a city ordinance in Appleton, Wisconsin prohibited African Americans staying overnight.[22]

Shortly thereafter, the Glidden Company struck gold, hiring Julian as the director of research in soy products, owing to his research in plants alkaloids and also, in part, to his fluency in German. In his seventeen years at Glidden, Julian secured dozens of patents and tremendous revenue from his development of soy-derived products, including an inexpensive processing method for cortisone (the only effective treatment at the time for rheumatoid arthritis), a flame retardant used on naval ships in World War II, and others. In 1953, Julian, limited in his research by Glidden’s commercial priorities (Glidden had tried to distract and appease Julian by sending him on vacation to Austria), struck out on his own. He established Julian Laboratories, hiring many African American scientists and continuing to pump out patents and revolutionary products.[23] In 1961, he sold Julian Laboratories for over two million dollars to Smith, Kline, and French, later part of GlaxoSmithKlein.

Julian continued to face racial discrimination throughout his career, even as one of the most influential chemists in the country. He was blocked from attending a scientific event at Chicago’s Union League Club[24] and chaffed under the stipulations for segregated hotels at national chemistry conventions.[25] Julian’s Oak Park, IL home was the object of racial terror on at least two occasions: attacked by arsonists before the family moved in and the following year a stick of dynamite was thrown at the home.[26] With his growing stature, he became more vocal in his objections to such racist practices. Slowly, he abandoned his earlier hopes that education and professional merit would earn blacks respect, as it seemed it had earned him as a chemistry doctoral candidate in Vienna. There Julian had seen with his own eyes the racial animus that some of his Jewish classmates had faced and that fueled the Nazi Party’s rise in the 1930s, openly anti-Black alongside being anti-Semitic. Surely those memories tempered his outlook, though never his ambitions, productivity, or achievements.[27]

_____

Author Biography

Kristina E. Poznan, PhD, is a scholar of American immigration and foreign relations history. Her work examines the relationship between transatlantic migration, migrant identities, and separatist nationalism in the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the context of migration to the United States. From 2017 to 2019 she was editor of Journal of Austrian-American History, sponsored by the Botstiber Institute for Austrian-American Studies and published by Penn State University Press. She is the managing editor of the Journal of Slavery and Data Preservation, published by Enslaved: Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade (Enslaved.org).

Image Sources

Portrait of Percy Lavon Julian (1899-1975), Digital Public Library of America, https://digital.sciencehistory.org/works/nk322f063.

Calabar beans (Physostigma venenosum). Franz Eugen Köhler, Köhlers Medizinal-Pflanzen (Germany, 1887), 237, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Physostigma_venenosum_-_K%C3%B6hler%E2%80%93s_Medizinal-Pflanzen-237.jpg.

Holwortel (Corydalis cava), https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Holwortel_(Corydalis_cava)_Boonkens_holwortel._radix_Cava_rubro_flore._Racine_Creuse._(titel_op_object),_RP-T-BR-2017-1-8-93.jpg.

Further Reading

- Cobb, W. M. “Percy Lavon Julian, Ph.D., Sc.D., LL.D., L.H.D., 1899-.” Journal of the National Medical Association 63, no. 2 (March 1971): 143-150.

- “Dr. Percy Julian, Chemist, Dies,” Washington Post, April 22, 1975.

- Witkop, Bernhard. “Percy Lavon Julian: April 11, 1899—April 19, 1975.” Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1980.

Further Viewing

Percy Julian—Forgotten Genius [DVD]. Directed by Stephen Lyons. WGBH, 2007. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/video/forgotten-genius/.

“How Percy Julian Became One of the World’s Greatest Scientists (feat. Jordan Peele),” Drunk History, Comedy Central (2014), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2sif5RI8XBU.

[1] “Julian Will Do Research in Chemistry in Austrian Universities,” Washington Post, June 9, 1929.

[2] Afro-American, July 16, 1932 (Percy L. Julian to Robert Thompson, Sept.13, 1929).

[3] Afro-American, July 23, 1932 (Julian to Thompson, October 9, 1929). Also available at https://blackcentraleurope.com/percy-lavon-julian-is-happy-and-healthy-in-viennese-society-1930/.

[4] Afro-American, July 23, 1932 (Julian to Thompson, October 9, 1929).

[5] David Taylor, “Percy Julian: A scientist makes inroads in chemistry and civil rights,” Humanities 28, no. 1 (January/February 2007): https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2007/januaryfebruary/feature/percy-julian.

[6] Afro-American, July 30, 1932 (Julian to Thompson, December 1929); Afro-American, August 27, 1932 (Julian to Thompson, July 5, 1930).

[7] Afro-American, July 23, 1932 (Julian to Thompson, October 9, 1929); Afro-American, July 30, 1932 (Julian to Robert Thompson, December 1929); Afro-American, August 6, 1932 (Julian to Thompson, March 26, 1930).

[8] Afro-American, July 23, 1932 (Julian to Thompson, October 9, 1929).

[9] Afro-American, July 16, 1932 (Julian to Robert Thompson, September 13, 1929); Afro-American, July 23, 1932 (Julian to Thompson, October 9, 1929).

[10] Afro-American, July 23, 1932 (Julian to Thompson, October 9, 1929).

[11] Bryan A. Wilson and Monte S. Willis, “Percy Lavon Julian: Pioneer of Medicinal Chemistry Synthesis” LABMEDICINE 41, no.11 (November 2010); Percy Julian—Forgotten Genius. [DVD], dir. Stephen Lyons (WGBH, 2007).

[12] Afro-American, July 16, 1932 (Julian to Thompson, September 13, 1929); Afro-American, July 30, 1932 (Julian to Thompson, December 1929).

[13] Afro-American, August 6, 1932 (Julian to Thompson, January 1, 1930); Afro-American, July 30, 1932 (Julian to Thompson, December 1929).

[14] Afro-American, September 3, 1932 (Julian to Thompson, December 14, 1930). Also available at https://blackcentraleurope.com/sources/1945-1989/percy-lavon-julians-doctoral-success-in-vienna-1930/.

[15] Afro-American, July 30, 1932 (Julian to Thompson, December 1929).

[16] Afro-American, September 3, 1932 (Julian to Thompson, December 14, 1930).

[17] Bryan A. Wilson and Monte S. Willis, “Percy Lavon Julian: Pioneer of Medicinal Chemistry Synthesis” LABMEDICINE 41, no.11 (November 2010).

[18] Afro-American, September 3, 1932 (Julian to Thompson, December 14, 1930).

[19] Letter from Percy L. Julian to W. E. B. Du Bois, August 10, 1931, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312), Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries, https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/pageturn/mums312-b059-i079/ – page/1/mode/1up.

[20] Neal B. Abraham, “Percy Lavon Julian,” Encyclopedia of Alabama, http://encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-2050.

[21] The draft title for this blog article was “The Two Princes of Calabar Beans: Percy Lavon Julian and Josef Pikl.”

[22] Peter Tyson, “Percy Julian the trailblazer,” https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/article/julian-the-trailblazer/.

[23] Sibrina Collins, “Percy Lavon Julian (1899-1975),” https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/julian-percy-lavon-1899-1975/.

[24] “Chemist Percy Julian pushed past racial barriers — amid attacks on his Oak Park home” Chicago Tribune, February 15, 2019, https://www.chicagotribune.com/opinion/commentary/ct-perspec-flashback-percy-julian-chemist-oak-park-20190206-story.html.

[25] “Letter from Percy L. Julian to John C. Warner,” February 3, 1956, Papers of Bernhard Witkop, Box 1, Folder 15. Science History Institute, Philadelphia. https://digital.sciencehistory.org/works/hx11xf25t.

[26] “Chemist Percy Julian pushed past racial barriers — amid attacks on his Oak Park home” Chicago Tribune, February 15, 2019.

[27] In the NOVA documentary, Julian claims to have assisted University of Vienna classmate Abraham Zlotnick escape the Holocaust. Julian’s papers are still in private possession and producer Stephen Lyons’s research materials for the film have not yet been donated to an archive. Once these two sets of materials are made available to researchers, this can be explored further.