VOICES

BIAAS Voices: Black Lives Matter – In Austria Too By: Farid Hafez

The murder of Afro-American George Floyd at the hands of a police officer elicited a global chorus of outrage. To see somebody being ruthlessly killed in eight minutes and 46 seconds leaves you speechless, if not angry and at least in pain–no matter who you are and where you live. In Austria, out of 8.9 million inhabitants, only an estimated 40,000 people have African ancestry (numbers from 2010, including Egypt and Tunisia).[1] Many would not have thought that the Black Lives Matter protest that started in the United States could spill over to the Alpenrepublik. And yet it did. Politician, medical doctor and political activist Mireille Ngosso planned a small rally with for 500 participants. Following the burgeoning interest online, she and other like-minded colleagues then registered a rally for 3,000 people. “We could not believe our eyes, when finally more than 50,000 people showed up at the rally,” she told me.[2] The next day, activist Naomi Saphira Weiser, who founded Black Lives Matter Vienna, organized a protest in front of the US Embassy in Vienna,[3] and more than 10,000 people showed up. So, why would so many people protest police brutality against Blacks in Austria? How do people in Austria relate to the murder of George Floyd in far-away Minneapolis? What does it mean when somebody in Austria declares ‘Black Lives Matter’ on the streets?

In an op-ed written by two Black Austrian activists in the daily Presse,[4] the authors remind us that police brutality against Black people has a long history in Austria. On May 1, 1999, a 25-year-old Marcus Omofuma, who had been detained after his requests for asylum were denied, was physically placed on a plane for his deportation to Nigeria. Omofuma tried to resist and was bound to his seat with adhesive tape, making him unable to move. He was gagged, his breath was severely restricted, and he died during the flight. When one week later the African community took to the streets, and 3,000 people protested against “racist police terror,” the police answered with one of the largest criminal investigation operations in Austria, the so-called “Operation Spring” on May 27, 1999. Eight hundred and fifty police officers stormed the homes of African activists, including refugees, and arrested 127 of them, who were subsequently presented by media as criminals. Three years later, the three police officers responsible for Omofuma’s death were convicted for “negligent homicide” and served only eight months in prison. The defense had argued that Omofuma, who had sought asylum but was declined, was culpable in his own death as he had resisted deportation. While Omofuma’s case has become the most infamous of police murder in Austria, it was not the only one—by far. In 1999, Senegalese-born Ahmed F. was killed during a drug control operation by the police. Other people can be mentioned: Richard Ibekwe, who died in custody; 19-year-old Johnson Okpara, who jumped out of a window during an interrogation in a juvenile detention center; Edwin Ndupu, Yankuba Ceesay, and Essa Touray. Mike B., an African American teacher, did not die but was severely beaten by Austrian police in a case of mistaken identity.[5]

Another infamous case was Cheibani Wague, who lost his life at the hands of ten people, six police officers, one medical doctor, and three ambulancemen on July 15, 2003. Four years later, the doctor and one police officer were convicted to seven months of suspended prison time. In the second instance, the police officer’s sentence was reduced to four months. The court’s reasoning behind this: The officer had behaved in accordance with training and therefore could not be held responsible for the disastrous training directed by the Austrian police force. This incident, and the ones mentioned above, demonstrate that police brutality and killing exists for Blacks in Austria. It also shows that this problem is more than a question of the prejudices of single police officers but rather a problem of structural racism.

Just two days before the first Viennese rally had started on June 4, 2020, the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI), which is an independent human rights monitoring body established by the Council of Europe, issued its sixth report on Austria, which unequivocally said: “Accounts of alleged practices of ethnic profiling by the police, against persons belonging to Black and Muslim communities in particular, continue to be reported.”[6] The Austrian government’s reaction was basically denial.[7] Furthermore, Austria ranks highest among all EU member states in terms of the mistrust of law enforcement bodies experienced by persons of African descent. And this plays out accordingly. In Austria, only 8% of people among respondents who felt racially or ethnically discriminated reported incidents of hate-crime, while the average was 16% in the European Union. The same report by the EU’s Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) shows that 66% of respondents with Sub-Saharan African background were stopped by the police in the five years before the survey, and 37% of them perceived it as racial profiling, which was the highest among participant countries (EU-28 average was 8%).[8] Although Austrian legislation prohibits racial profiling and even offers a legal framework to deal with complaints, there have been only two judgments on racial profiling so far. Yet, according to the Anti-Discrimination Body in Styria, only seven of 1,518 cases on alleged mistreatment by police were submitted before the courts by the public prosecutor’s office.[9] According to another study, 40% of the respondents who had already dealt with courts stated that they had not been treated with appropriate respect by the courts as a result of their African ancestry. Even worse: “70 percent do not believe in the equality of people with black skin color in the Austrian legal system.”[10] These are alarming numbers for a country that prides itself with values such as equality and the rule of law. And it clearly reveals the neglected racial divide.

Hence, no wonder that while the large majority of white people who rallied on June 4 were holding posters with slogans such as “Black Lives Matter” and “Justice for George Floyd,” many of the Black protesters focused on police brutality and racism in Austria, saying “Austria has a racism problem.” On one side, the movement in Austria has a clear US-American imprint. While BLM Austria, which organized the rally in front of the US embassy, is not formally connected to BLM in the US, it has been clearly influenced by the mother movement, as the slogans, images and the protest culture reveal. BLM Austria was initiated by Naomi Saphira-Weiser, whom I first met in a lecture I had given in Salzburg on the life of Malcolm X. Later, she wrote in a piece for Vice that it was my biography on Malcolm X that triggered Naomi (who writes with her pseudonym Imoan Kinshasa) to reflect deeper about her own Blackness and subsequently on questions of self-respect and self-determination.[11] On the other side, the demonstrations also clearly reveal how US experiences were translated into an Austrian context. Slogans such as “Against Racism and Police Brutality. May 1, 1999 Omofuma” reminded viewers that this demonstration is but one galvanizing event in a long history of police brutality, structural and institutional racism. Rallies took place in eight out of nine Austrian states and mobilized nearly 100,000 people on the streets within one week. This is an incredibly large number given the small size of the country. As a participant observer at the largest rally in Vienna, I would regard the majority of demonstrators as white and under the age of 30. They shouted their slogans with an American accent that suggests a lasting impact of the “Coca-Colonization”[12] on a new generation in the times of Netflix and Instagram that also absorbs the politically subversive movements of the ‘American way of life.’[13] And the organizers and activists at the forefront are no longer people in precarious positions as 20 years ago. Today’s Black leaders in Austria are represented by a young generation of Blacks who were born or at least raised in Austria, backed by Black people of color in political parties such as Mireille Ngosso from the Social Democratic Party or Faika El-Nagashi from the Greens, both of whom mobilized for the June 4th event.

The protagonists of the demonstration are aware that there is still a long way to go on the road to racial justice. Following the rally, Mireille Ngosso recalls being asked by journalists whether there is racism in Austria. To her, such questions reveal the extent of the negligence by the white establishment. But she is optimistic. Black Movement Austria was born out of the protests, and seeks to organize Black people to protest, educate and spread awareness in order to change the reality of Black people in Austria. While BLM has become the largest social movement in the United States since the 1960s and protesters are questioning entire institutions like the police, this movement of young people in Austria might have the potential to challenge structural racism on a larger scale than ever before.

About Farid Hafez:

Farid Hafez is a Vienna-based political scientist at Salzburg University, Department of Political Science and Sociology. In 2017, Farid was a Fulbright Visiting Professor at University of California, Berkeley. Hafez is an associate of Georgetown University’s The Bridge Initiative and Faculty Affiliate at Rutgers University’s Center for Security, Race and Rights. Hafez has more than 100 publications and publishes in internationally renowned journals such as Politics and Religion, Oxford Journal of Law and Religion, Patterns of Prejudice and German Politics and Society.

Further Reading:

Ellerbe-Dueck, Cassandra. “Networks and ‘Safe Spaces’ of Black European Women in Germany and Austria.” Negotiating Multicultural Europe. Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2011. 159-184.

Hafez, Farid. “From Harlem to the ‘Hoamatlond’: Hip-Hop, Malcolm X, and Muslim Activism in Austria.” Journal of Austrian-American History 1.2 (2018): 159-180.

Jirovsky, Elena, et al. “‘Why should I have come here?’-a qualitative investigation of migration reasons and experiences of health workers from sub-Saharan Africa in Austria.” BMC health services research 15.1 (2015): 1-12.

Lazarus, Suleman. “‘Some Animals Are More Equal Than Others’: The Hierarchy of Citizenship in Austria.” Laws 8.3 (2019): 1-19.

Okyerefo, Michael Perry Kweku. “‘I Am Austro-Ghanaian’: Citizenship and Belonging of Ghanaians in Austria.” Ghana Studies 18.1 (2015): 48-67.

Weichselbaumer, Doris. “Discrimination against migrant job applicants in Austria: An experimental study.” German Economic Review 18.2 (2017): 237-265.

Wodak, Ruth, and Bernd Matouschek. “‘We are dealing with people whose origins one can clearly tell just by looking’: Critical discourse analysis and the study of neo-racism in contemporary Austria.” Discourse & Society 4.2 (1993): 225-248.

Notes

[1] Inou, Simon and Beatrice Achaleke (eds.). 2011. Schwarze Menschen in Österreich Lagebericht. Afrika und AfrikanerInnen in der österreichischen Schul- und Hochschulbildung, Jahresbericht 2010, http://www.m-media.or.at/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Lagebericht-Schwarze-Menschen-%C3%96sterreich2010.pdf

[2] Wien ORF, 50.000 bei “Black Lives Matter”-Demo, June 4, 2020, https://wien.orf.at/stories/3051825/

[3] U. S. Embassy Vienna, Demonstration Alert, Austria, July 2, 2020, https://at.usembassy.gov/demonstration-alert-u-s-embassy-vienna-austria-july-2-2020-2/

[4] Inou, Simon and Berverkly Mtui, Nehmt die “Black Lives Matter”-Bewegung ernst, Die Presse, June 17, 2020, https://www.diepresse.com/5827354/nehmt-die-black-lives-matter-bewegung-ernst

[5] Inou, Simon, Polizeigewalt gegen Afrikaner: Eine Chronologie, Die Presse, January 8, 2010, www.diepresse.com/474710/polizeigewalt-gegen-afrikaner-eine-chronologie

[6] ECRI Report On Austria (sixth monitoring cycle), Adopted on April 7, 2020 Published on June 2, 2020, https://rm.coe.int/report-on-austria-6th-monitoring-cycle-/16809e826f

[7] ORF Religion, Europarat: Kopftuchverbot in Österreich überarbeiten, June 2, 2020, https://religion.orf.at/stories/3003262/

[8] FRA, Being Black in the EU Second European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey Summary, https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2019-being-black-in-the-eu-summary_en.pdf

[9] Antidiskriminierungsstelle Steiermark, 2019. Antidiskriminierungsbericht Steiermark 2018, https://www.antidiskriminierungsstelle.steiermark.at/cms/dokumente/12754830_154135785/d90afb5a/jb2018a.pdf

[10] Simone Philipp und Klaus Starl, Lebenssituation von “Schwarzen” in urbanen Zentren Österreichs Bestandsaufnahme und Implikationen für nationale, regionale und lokale Menschenrechtspolitiken, http://www.etc-graz.at/typo3/fileadmin/user_upload/ETC-Hauptseite/publikationen/Selbststaendige_Publikationen/ETC-Neumin-Web.pdf

[11] Kinshasa, Imoan. Der Tag, an dem ich Schwarz wurde, August 21, 2018, https://www.vice.com/de/article/8xb39a/der-tag-an-dem-ich-schwarz-wurde

[12] Reinhold Wagnleitner, 1994. “Coca-Colonization and the Cold War: The Cultural Mission of the United States in Austria after the Second World War,” Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

[13] Hafez, Farid. “Political beats in the Alps: On politics in the early stages of Austrian Hip Hop music.” Journal of Black Studies 47.7 (2016): 730-752.

Image Captions

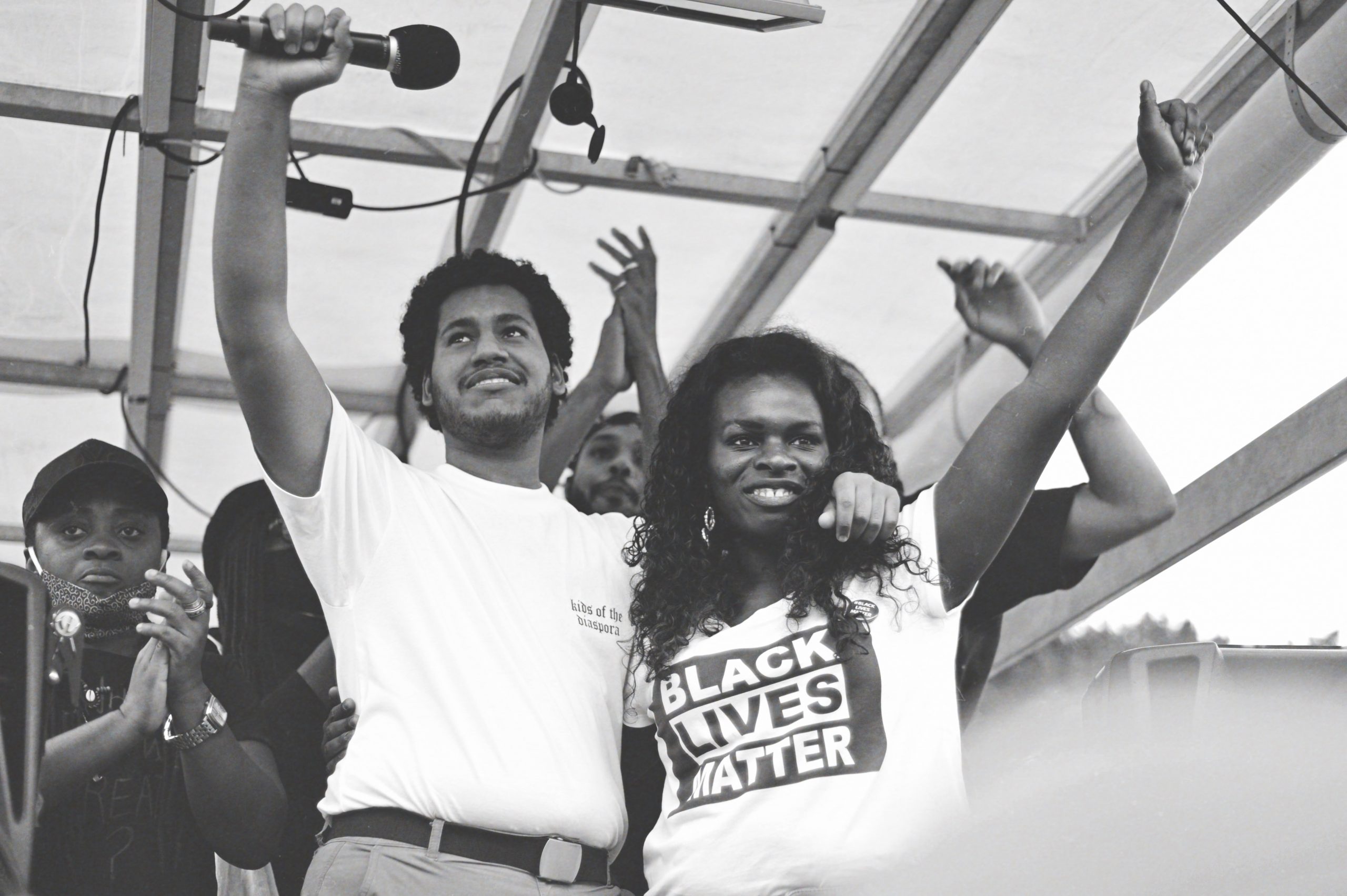

Picture 1: Mugtaba Hamoudah and Mireille Ngosso, two leading activists of the rally in Vienna that mobilized more than 50,000 people on the rostrum.

Created with RNI Films app. Preset ‘Agfa Scala 200 Faded’

Picture 2: Thousands of people gathering in front of the historical Karlskirche in Vienna.

Created with RNI Films app. Preset ‘Agfa Scala 200 Faded’

Picture 3: Young protesters holding a Black Lives Matter-banner.

Created with RNI Films app. Preset ‘Agfa Scala 200’

Copyright of all photos: Asma Aiad