Part II of Megan Brandow-Faller’s Interwar Vienna’s ‘Female Secession’: From Vienna to New York and Los Angeles

By Megan Brandow-Faller

PART II

Artists like Vally Wieselthier, Emmy Zweybrück-Prochaska, or Maria Likarz-Strauss, who created decorative art and handcraft that was formally and thematically provocative, clashed with the regime’s attempts to resurrect the hierarchy of the arts and retain biologically defined gender roles. The regime tended to prefer clarity in art and design and emphasized, on the one hand, a resurgence of traditional handcraft skills and, on the other, industrially-produced design objects for the masses. The Viennese tradition of decorative arts—a field known for its defiance of traditional boundaries of high/low and masculine and feminine fields of expression—was met with outright hostility, added to the Jewish nature of its artist base and patronage networks.

For the majority of Wiener Frauenkunst (WFK) artist-craftswomen, accommodation with Hollenstein and the activities of the coordinated Association of Austrian Women Artists was neither desirable nor possible given their racial classification as Jews. A large number of members and associated artists were forbidden to work, forced to emigrate, or deported. Hilde Jesser-Schmid and Erna Kopriva (KGS faculty in painting and applied art, respectively) were forbidden to work in 1938 and forced into retirement; they were reactivated as KGS teaching staff after the war.[1] Wiener Werkstätte (WW) artists who fled Austria and emigrated to safer countries included Likarz-Strauss (to Yugoslavia and Rome), Hilde Wagner-Ascher (to London), Mitzi Friedmann-Otten (to New York), Gabi Lagus-Möschl (to Italy), Lucie Rie-Gomperz (to London), and Fritzi Löw-Lazar (to Denmark in 1933, to England from September–October 1939, and to Brazil from 1939 to 1955; she finally re-emigrated back to Vienna in 1955).[2] Among the WFK’s visual artists forced into exile was painter and children’s book illustrator Bettina Ehrlich-Bauer (1903–1985), the niece of Adele Bloch-Bauer, who participated in five major WFK exhibitions (1930, 1931, 1933, 1934, 1938) and was known for her unique, seemingly childlike and naïve variant of magic realism.[3] Additionally, a sizeable number of members were murdered in concentration camps, including sculptor Grete Neuwalder-Breuer, painter/graphic artist Helene Taussig (1879–1942), Böhm school member and Kunstschau 1908 participant Marianne Deutsch (1885–1942), and possibly others like ceramicist and Wieselthier protégé Kitty Rix, who disappeared from written sources in the mid-1930s.[4]

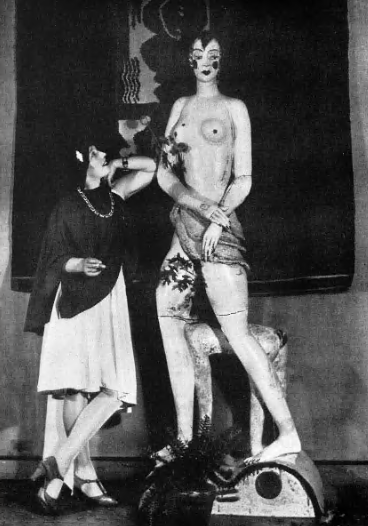

By the time the WFK was dissolved, several of its leading forces had already established themselves in exile. Wiener Frauenakademie (WFA) alumna Wieselthier, coming from an assimilated Jewish background typical of interwar artist-craftswomen, left a decade before the Anschluss. In light of the growing financial problems plaguing the WW, Wieselthier decided to emigrate to New York in 1928 (first provisionally and then definitively after the WW’s 1932 collapse). She capitalized on her favorable reception at the 1928/29 International Exhibition of Ceramic Art, an important exhibition originating at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that traveled to five American cities. In addition to Wieselthier, other Austrian participants included Susi Singer, Gudrun Baudisch, Hertha Bucher, Rix, and Dina Kuhn. Curating an image in America as a naïve, happy-go-lucky child-woman, Wieselthier rebranded herself as a ceramic sculptor, creating oversize earthenware figures that transported female craftiness and wheel-based vessel techniques into the realm of the monumental. Works such as the mannequin-like Modern Youth (1928), exhibited at her first solo exhibition in New York, showed the artist’s proclivity for self-reflexive parody at its height (see image). Like her trademark Frauenköpfe, the construction and decoration of Modern Youth was animated by a transparent artificiality that troubled the idea of “natural” feminine beauty. Enjoying a distinguished exhibition record of one-woman shows and regular participation in group exhibitions, Wieselthier was celebrated in the Austrian press as “conquering the new world” and “teaching America a lesson” about the expressionist possibilities of the medium, most readily taken up by the Cleveland school of ceramic sculptors.[5]

Notably, Wieselthier’s deliberately untutored mode of practice was at odds with the pedagogical emphasis on skill associated with other German-Jewish American émigrés like Bauhaus-trained ceramicist Marguerite Wildenhain, who taught a generation of American ceramicists at Pond Farm, California.[6] Wieselthier likewise disseminated the Raumkunst ideal central to the WFK through her involvement in Contempora, a New York–based design cooperative aspiring to an ideal collaboration between art and industry through the creation of high-quality, affordable prototypes for manufactured production. Cofounded by Paul Wiener, Bruno Paul, Lucien Bernhard, and Paul Poiret, Contempora showcased harmonized model interiors featuring Wieselthier’s ceramic sculpture and textile designs.

Wieselthier maintained close contacts to the Austrian émigré community through architect Wolfgang Hoffmann (Josef Hoffmann’s son) and other WFK/WW members in exile in New York and Los Angeles. Böhm student Singer held Sunday afternoon salons in her Hollywood bungalow, which became a gathering place for the Los Angeles émigré community and New York–based artists like Wieselthier. While Wieselthier’s emigration to New York was undertaken ten years before the Anschluss, Singer’s Californian exile was, like the majority of WW/WFK/Werkbund artists, an involuntary measure necessitated by her status as a Jew. Singer had lived in the remote village of Grünberg am Schneeberg since 1924, where she produced original ceramics for the WW that won prizes at the 1925 Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes in Paris (gold medal), the 1934 Austrian Exposition in London (certificate of honor), the 1935 World Exhibition in Brussels (gold medal), and the 1937 Exposition internationale des arts et techniques dans la vie moderne in Paris (gold medal). One year after her last solo exhibition at Vienna’s Galerie Würthle in March 1937, Singer was left alone with her infant son when her non-Jewish husband died in a mining accident. Like Wieselthier, Singer’s participation in the 1928/29 International Exhibition of Ceramic Art proved invaluable to obtaining a visa and brokering contacts to dealers and galleries.[7] Through the help of a WFA classmate, Liesel Borsook, Singer settled in Los Angeles in 1939 with the expectation that the film industry might generate interest in her work. She established close relationships with several Los Angeles-area colleges and universities, teaching ceramics courses and winning a fellowship at Scripps College in 1946 where, like Wieselthier, she experimented with large-scale figures and glazes. But her trademark work remained small-scale figural sculpture that superimposed the lyrical, pastoral subjects of her Viennese period with “life situations reflective of Hollywood, the California lifestyle, and modern woman.”[8]

Wieselthier and Singer successfully introduced Viennese Expressionist ceramics to American audiences, not only earning critical acclaim and recognition for their work, but decisively influencing a younger generation of ceramic sculptors. Meanwhile two other Austria-America émigrés—Zweybrück-Prochaska and Liane Zimbler— were to make similar strides in the fields of pedagogy and architectural design, disseminating Secessionist ideas of child creativity and the spirit of Wiener Frauenkunst exhibitions throughout the postwar United States.

(To be continued in Part III)

.

Author Biography:

Megan Brandow-Faller is Associate Professor of History (with tenure) at the City University of New York, Kingsborough. Her research focuses on art and design in Secessionist and interwar Vienna, including children’s art and artistic toys of the Vienna Secession; expressionist ceramics of the Wiener Werkstätte; folk art and modernism; and women’s art education. She is the editor of Childhood by Design: Toys and the Material Culture of Childhood, 1700-present (Bloomsbury 2018) and the author of The Female Secession: Art and the Decorative at the Viennese Women’s Academy (Penn State University Press, 2020).

To learn more, please visit: https://www.meganbrandowfaller.com/

Notes

[1] Personnel Files Kopriva & Jesser-Schmid, UAKS (Universität für angewandte Kunst, Sammlungen und Archiv).

[2] KünstlerInnen Datenbank, ÖGBA (Österreichische Galerie Belvedere Archiv)

[3] Winklbauer, Andrea Winklbauer, “Bettina Ehrlich-Bauer und die neue Sachlichkeit.” In Sabine Fellner and Andrea Winklbauer, Die bessere Hälfte (Vienna: Jewish Museum, 2016), 165–75.

[4] Iris Meder,” Arbeitende Frauen: Jüdische Designerinnen und Architektinnen.” In Fellner and Winklbauer, Die bessere Hälfte, 98; Winklbauer and Fellner, Die bessere Hälfte, 212, 214.

[5] For Wieselthier’s American influence, see Janet Koplos and Bruce Metcalf. Makers: A History of American Studio Craft. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

[6] Jenni Sorkin, Live Form: Women, Ceramics, and Community (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 55-104.

[7] Elaine Levin, “Vally Wieselthier, Susi Singer.” American Craft 46 (Dec. 1986 / Jan. 1987), 49.

[8] Christy Johnson, and Billy Sessions. “Women’s ‘Werk:’ The Dignity of Craft at the American Museum of Ceramic Art.” Ceramics 61 (2005), 79.

Image Caption

Photograph of Vally Wieselthier with Modern Youth, 1928. Glazed earthenware. From

DKD 64, no. 7 (1929): 38.