‘The Vacation Vagaries of the Diplomatic Folk’: Ambassador Hengelmüller’s Summers in Bar Harbor, ME

By Kristina Poznan

Austria-Hungary’s diplomatic seat in the United States stood, naturally, in Washington, D.C., but the capital city’s sweltering summer climate drove American politicians and foreign diplomats alike out of the city in the summer months. Among them were Ladislas Hengelmüller von Hengervár, head of Austria-Hungary’s delegation to the United States from 1894 to 1913, and his family. President Grover Cleveland established the precedent of summer escape from Washington, which continued under William McKinley. “The vacation vagaries of the diplomatic folk, including and headed by President McKinley and his cabinet, have been the principal matter of interest to the public relation to members of the corps,” opined the International monthly magazine. “These great people set the fashion for many watering places and resorts by mountain and sea, and the struggles of the proprietors to secure one or more of them are often keen.”[1] In essence, ambassadors’ comings and goings from Washington gave shape to the diplomatic year.

Their locations of choice were as wide-ranging as the Virginia mountains, upstate New York, and the Jersey Shore. But “New England is, in the eyes of the majority of foreign governments, the ‘summer capital of the United States,” Waldon Fawcett reported for New England Magazine. “The diplomats who are stationed in this country as the accredited representatives of foreign powers almost without exception spend the vacation season in the northeastern section of Uncle Sam’s domain,” he explained,[2] owing to the more temperate summer climate. The Austrian Ambassador and Baroness Hengelmüller were, sources reported, “unwavering in their allegiance to Bar Harbor, Maine, as a vacation retreat.”[3] As regulars there for over a decade, Austro-Hungarian officials could consistently expect the relocation of American operations there each summer, and the Hengelmüllers could take up the previous summer’s amusements and social diversions with little new planning.

Hengelmüller began his U.S. post as Minister of the Austro-Hungarian legation, but was upgraded to Ambassador when the Legation officially became an Embassy in 1902. A few years later Hengelmüller was named a baron owing to his illustrious diplomatic posting. His ambassadorship soon made him eligible to become the Dean of the diplomatic corps in 1910, as the longest-serving foreign diplomat in the United States, which carried a great deal of clout. The social press in Washington, New England, and throughout the country reported frequently on the Baron, Baroness Marie, and their daughter, Mila. Hengelmüller operated out of the embassy in Washington during much of the winter, but spent months each year in Lenox, Massachusetts and summers, almost invariably, in Bar Harbor, which boasted the “largest contingent on the coast” of summer diplomatic residences.[4] The Washington Sunday Star identified the Baron and Baroness as “among the most popular of the social set” there. When they missed a summer in Maine to return to Europe, their absence was considered newsworthy; they had been “greatly missed.”[5] The Hengelmüllers’ presence in Maine offered prestige to the town and others in their orbit there, making their absence for a single season conspicuous.

Although the Hengelmüllers were consistent in their choice of Bar Harbor as their summering spot, they stayed at various properties there. Initially the Hengelmüllers just rented rooms at the Lyman Hotel, but in time the main contingent of the Austro-Hungarian legation/embassy would relocate and operate out of a grand rented “cottage.” They rented the Castlemaine Cottage, Band Box (for example, in 1897), Treviot Villa (1908), and, most frequently, the Higgins Cottage (1906, 1910, 1911, and likely other years also).[6] These buildings were situated on or near the elite Cottage Road, which rivaled some streets in Newport, Rhode Island in grand resort architecture “The first arrivals are Baron and Baroness Hengelmüller and their little daughter,” the Washington Post reported in 1910, “who will be at the Alcenus Higgins cottage, which will be the headquarters of the Austrian embassy this summer. The first secretary of the embassy, Count Felix von Bruselle-Schaubeck and Count Ladislas Cziraky, also of the embassy staff, were among the week’s arrivals.”[7] This was no mere getaway; it became the literal base of diplomatic operations for several months.

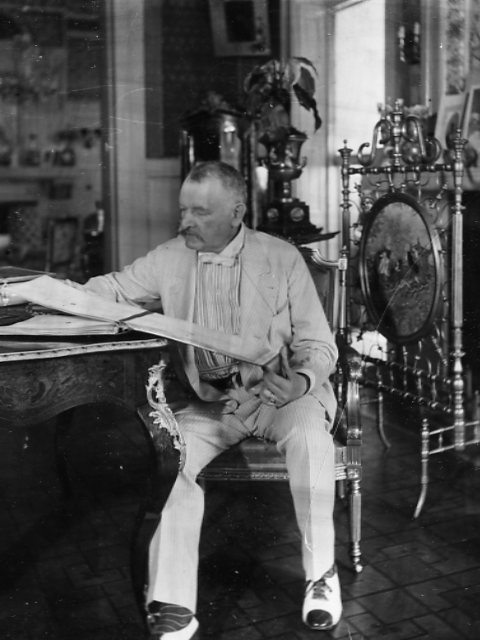

Mount Desert Island served as the Hengelmüllers’ summer playground, but serious work proceeded apace. The ambassador’s correspondence from Bar Harbor was voluminous, so much so that the researcher examining Foreign Ministry files from this period becomes just as accustomed to his letters being signed from Maine as from the American capital. From Hengelmüller’s desk at Bar Harbor came correspondence on matters as varied as the aftermath of the Lattimer Massacre in 1898, in which several striking Austro-Hungarian coal miners had been killed,[8] and return migration initiatives, on which he authored a lengthy report in August 1908.[9] The latter example suggests that the slower pace in Bar Harbor afforded Hengelmüller the time to write up in greater detail his thoughts on American affairs for his superiors in Vienna that he and his staff had been collecting information on in the preceding months.

But leisure was no small part of the experience; the salubrious climate and elite social scene were paramount in Bar Harbor. “The summer life of the diplomats is . . . quite as interesting as their doings at the seat of government in winter,” New England Magazine reported. “For one thing there is less formality and Americans who come in contact with them gain a much better idea of the personalities of these interesting foreigners.” [10] From the New York Times and Bar Harbor Record, we can track how the Hengelmüllers used their leisure time, from yacht parties[11] to playing golf at the Kebo Valley Club.[12] Often favored guests, they were also gracious hosts. “The Austro-Hungarian ambassador and Baroness Hengelmüller entertained at dinner Tuesday night, at Teviot Villa, Bar Harbor, where they are spending the season,” the Washington Post reported. “Their guests, who were asked to meet Mr. and Mrs. Winston Churchill, were Mr. and Mrs. Linzee, Mr. and Mrs. Weeks, Mr. and Mrs. Butler Duncan, Jr., Mrs. Platt Hunt, Mr. Johnson, Baron Haymerle, and Prince Vincent zu Windisch-Graetz.”[13] This guest list is representative of the elite company the Hengelmüllers kept in Maine.

Hengelmüller, aging and less than thrilled about the growing transatlantic hostilities preceding the outbreak of the Great War, resigned his diplomatic post in early 1913 to retire after decades of service to the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Ministry. He passed away in 1917 at the Adriatic resort town of Abbazia (now Opatija, Croatia), a place not entirely unlike Bar Harbor.[14] Bar Harbor has not retained its prestige compared to places with more name recognition and easier highway access today like Cape Cod and Newport, suffering from both the Great Depression and a devastating fire in 1947. But it remains a quaint community and tourist destination. You can stay at Castlemaine Cottage, now a bed and breakfast, which still boasts that “Baron and Baroness Hengelmüller were the most famous residents.” [15] Although the long removals of the governmental political elite from Washington have ended in the age of air conditioning, researchers should not be surprised to find heaps of diplomatic correspondence from mountain and beach resorts in the archives.

Author Biography:

Kristina E. Poznan, PhD, is a scholar of American immigration and foreign relations history. Her work examines the relationship between transatlantic migration, migrant identities, and separatist nationalism in the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the context of migration to the United States. She currently teaches in the History Department at New Mexico State University. From 2017 to 2019 she was editor of Journal of Austrian-American History, sponsored by the Botstiber Institute for Austrian-American Studies and published by Penn State University Press.

Further Reading:

Aron, Cindy. Working At Play: A History of Vacations in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Helfrich, G. W. and Gladys O’Neil. Lost Bar Harbor. Lantham, MD: Down East Books, 2015.

Phelps, Nicole M. U.S.-Habsburg Relations from 1815 to the Paris Peace Conference: Sovereignty Transformed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Yetter, Luann. Bar Harbor in the Roaring Twenties: From Village Life to the High Life on Mount Desert Island. Charleston, SC: The History Press, History Press 2015.

Notes

[1] A.J. Halford, “Matters Diplomatic,” The International: An Illustrated Monthly Magazine of Travel and Literature 3 (1897), 288.

[2] Waldon Fawcett, “Glimpses of Washington: The Summer Life of the Diplomats,” New England Magazine XXXIV, no. 5 (July 1906), 521.

[3] Ibid., 523.

[4] Halford, “Matters Diplomatic,” 289.

[5] “At Bar Harbor,” Sunday Star [Washington, D.C.], June 10, 1906, 9.

[6] “Bar Harbor, Maine: The Museum in the Streets,” https://barharborvia.files.wordpress.com/2016/06/bar-harbor-panels-1-29-revised-24may2012.pdf; Social Register XI, no. 8 (August 1897); Washington Post, May 22, 1911.

[7] “Envoys at Seashore: Diplomats Establish Summer Embassies at Bar Harbor,” Washington Post, June 26, 1910, 8.

[8] Mr. Hengelmuller to Mr. Hay, Bar Harbor, August 10, 1899. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1899/d19

[9] For one example of Hengelmüller’s extensive correspondence from Bar Harbor, see Hengelmüller to Aehrenthal, August 3, 1908, Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv, PA XXXIII, 100.

[10] Fawcett, “Glimpses of Washington,” 522-523.

[11] “Bar Harbor Doings,” New York Times, July 12, 1902.

[12] Bar Harbor Record, June 21, 1911.

[13]Washington Post, August 13, 1908.

[14] Washington Post, April 27, 1917.

[15] “Bar Harbor, Maine: The Museum in the Streets.” https://barharborvia.files.wordpress.com/2016/06/bar-harbor-panels-1-29-revised-24may2012.pdf

Image Credits

Our thanks to the Jesup Memorial Library for the permission and scanned images of historic Bar Harbor postcards.