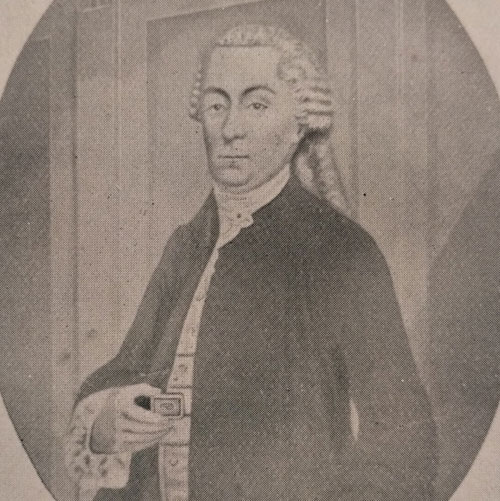

The Habsburg Monarchy’s Man on the Ground: Baron de Beelen-Bertholff

By Jonathan Singerton

August should have been a relatively safe time for transatlantic travel, but calm seas and prosperous winds could still give way to fierce storms and howling gales. “At around two in the morning,” recorded one poor soul on the George Washington in 1783, “we awoke for the second time to one of the most monstrous storms, we were not even finished pulling up the sails before the waves dashed abroad from all sides; most of the sailors had to finish their work half-swimming.”[1] Forty days later as the ship finally drifted up the Delaware River to reach the American capital, Philadelphia, only to learn that in the weeks prior the city’s inhabitants fell victim to a severe “Fall Fever,” claiming thirty lives a day at its height.

Such an arrival was an inauspicious start for any family in the young American republic, but the Beelen-Bertholffs were no ordinary family. The Habsburg ruler Joseph II handpicked the family’s patriarch, Baron Frederick Eugene François de Beelen-Bertholff, to become his imperial commercial adviser in the new United States of America. Such a position had never been established before and the baron’s remit was laid out by Vienna. For the next seven years, Baron Beelen-Bertholff was to:

- act as the official representative for all Habsburg merchants in the United States,

- facilitate greater trade between the United States and Habsburg Monarchy through pursuing a trade treaty with local leaders, and

- gather intelligence on any and all commercial prospects for the Habsburg Monarchy in the United States.

The mission represented one of the Habsburg Monarchy’s greatest hopes at procuring greater international trading ties. The newly independent United States of America was a vital player in the Habsburg strategy. Transatlantic trade had boomed between the two nations during the War of Independence. Ports like Ostend and Trieste grew rich from new ventures focused on trading local manufactures—weapons from Liege in the Austrian Netherlands and glassware from Bohemia—in exchange for American tobacco and sugar.

The problem, however, was the Habsburg Monarchy was far from alone in establishing relations with the United States. In the same month the Beelens arrived in Philadelphia, the representatives of Saxony and Portugal arrived, too.[2] France, allied with the United States since 1778, was already on its second ambassador. Even Sweden had a man on the ground before the Habsburgs.[3] Beelen had to move quickly.

But as soon as the baron and his family stepped ashore from the George Washington, he fell sick. Fearing the worst, they moved to the countryside outside Philadelphia. The baron’s wife, Jeanne-Marie Therese, nursed him slowly back to health as their two sons and daughter enjoyed their new surroundings. A personal sketchbook survives from this period, probably the cherished possession of one of the children. It is replete with depictions of their farmstead on the banks of the Schuylkill River and a hand-drawn portrait of George Washington features prominently, occupying the largest space in the book.

After a slow recovery some weeks later, Beelen got to work. From 1783 to 1789, he sent quarterly reports to ministers in Brussels and Vienna. These reports described vividly the American way of life and articulated how latest clothing fashions, price changes, and new manufactures might benefit Habsburg trade. Beelen scoured local and regional newspapers for his sources, reached out to merchants all over the United States, and pressed his contacts for information. His range grew rapidly to encompass information about the entire North American coastline, covering everything from women’s petticoats to the abundance of snuff in Charleston.[4] He logged every ship that entered Philadelphia’s harbour from 1784 to 1789. He monitored price lists and, more surreptitiously, kept track of all the other European representatives in America.[5]

Between 1784 and 1789, Beelen sent back twenty-three reports containing information regarding 349 different topics. By the end of his mission, he had reached some 1,564 pages.[6] Getting such voluminous and precious paper back to Vienna sometimes proved challenging. Beelen often waited for a ship he knew was going directly to an Austrian port like Ostend or Trieste, but sometimes relied on ones to Bordeaux, London, Bremen, or Cadiz. From there, these reports made it to Vienna through the wider Habsburg diplomatic service, which had been briefed on the urgency of forwarding these materials.

The Viennese court cared a great deal about Beelen’s reports, which they disseminated across the Habsburg lands. Governors in Trieste and Fiume received summaries to distribute among local merchants. The regional administration of the Austrian Netherlands performed the same mediation to many Flemish industrialists, such as the owner of a fabric factory in Tournai who got a copy of Beelen’s report on “the use of carpets in North America”[7] – vital knowledge if you wanted to sell the right taste of textiles to a large market.

As Beelen’s mission went on, the political situation in the Habsburg Monarchy deteriorated. Unrest grew in response to Joseph II’s ambitious reforms. In Brussels, where the committee overseeing Beelen’s mission was based, a violent revolution broke out in 1787 and then again in 1789. Beelen was left without updates or further instruction for most of his time in the United States and ministers began to question his worth. During a visit to Vienna in 1787, his half-brother Maximilian overheard conversations about his recall from Philadelphia and swiftly warned him.

Beelen panicked. Apart from reporting on American prosperity, he sought to benefit fro it by joining in on various land speculation schemes. By 1790, Beelen owned three estates (stocked with servants) in Philadelphia, about 2,100 hectares near Pittsburgh, and another 4,000 hectares of land in Ohio and Kentucky.[8] His future clearly lay with the United States and he and his family did not want to go back. He started informing Vienna of his ill health, brought on by a stomach tumour, which forced him to have debilitating surgery.[9] Whether true or not, Beelen effectively argued that he was unable to make any potential journey back to Europe.

Cunning but crucial, Beelen was an instrumental figure in early Austrian-American relations. His family continues to live on in the United States today and his reports still provide historians with one of the richest views into the commercial world of early America as well as the goals of early Habsburg transatlantic trade.

Jonathan Singerton is a specialist on the early connections between the Habsburg Monarchy and North America. He recently completed his PhD entitled “Empires on the Edge – The Habsburg Monarchy and the American Revolution 1763-1789” at the University of Edinburgh. He is currently a Plaschka Fellow at the Institute for Modern and Contemporary History at the Austria Academy of Sciences, Vienna.

Notes:

[1] From in Ignaz von Born, “Herrn Prof. Märters erstes Schreiben an Hrn. Hofrath von Born über seine Reise von Europa nach Philadelphia in Nordamerika (dated 15th September 1783),” Physikalische Arbeiten der einträchtigen Freunde in Wien, No. 3 (Vienna, 1785), 53. Professor Franz Joseph Märter was a botanist who led a scientific expedition to the US in the 1780s. He and his team were aboard the same vessel as the Beelen family in 1783.

[2] See William E. Lingelbach, “Saxon-American Relations, 1778–1828,” AHR, 27 (1911–12), 525–30.

[3] Baron Samuel Gustaf Hermelin. See H. A. Barton, “Sweden and the War of American Independence,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 3 (July, 1966), 408-430.

[4] Jonathan Singerton, “Chapter Five: The First Habsburg Representatives in the United States of America 1783-1789,” in ‘Empires on the Edge: The Habsburg Monarchy and the American Revolution 1763-1789’ (Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2018), 140-169.

[5] Neither the British Consul John Temple, nor the Swedish representatives supplied their respective courts with more information than Beelen. Temple Papers contained within The Bowdoin and Temple Papers Series 1756-1809, I-III, (Boston, 1897); Leos Müller, “Swedish-American Trade and the Swedish Consular Service, 1780-1840,” International Journal for Maritime History, 14, No. 1 (June 2002), 173-188.

[6] Hanns Schlitter published Beelen’s reports, as Die Berichte des ersten Agenten Österreichs in den Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika (Vienna, 1891). However, Schlitter heavily edited the correspondence and chose selected reports from the collection. By my calculations he published only the following fractions: K.182a (31%), K. 182b (41%), K. 182c (32%), K. 182d (29%), K. 182e (15%).

[7] For Trieste and Fiume, see: Archivo di Stato di Trieste, Deputazione di Borsa, Series VII, C. 75, fol. 58 “Communicazione del Governo per la nomina del Barone di Bellen a Consigliere di Commercio presso di Congresso Americano”; Serie VII, C.127, fol.13 “Trasmissione del Governo delle tabelle inviate dal consiglieri Barone de Beelen, dei prezzi delle merci in Filadelfia”; Finanz und Hofkammerarchiv, Neue Hofkammer, Kommerz Litorale, Akten, K. 904 Fasz. 104, fols. 1245, 1272-1278, 1299. For the Tournai businessman, see: Rapport du Committee sur les Deux Reports de Beelen en Philadelphie, 16th September 1784, HHStA, DDB Rot, K. 182e, fols. 49-96.

[8] Jonathan Singerton, “The Fate of Baron von Beelen-Bertholff” in ‘Empires on the Edge: the Habsburg Monarchy and the American Revolution 1763-1789’ Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2018), 220-228.

[9] Beelen to Trauttmansdorff, 28th September 1788, HHStA, Belgien, DDB Rot, K. 182e, fols. 256-259.

Further Reading:

Agstner, Rudolf. Austria-Hungary and its Consulates in the United States of America since 1820. Vienna: Litt Verlag, 2012.

de Beelen Mackenzie, Anton. History of the Gazzam Family—together with a sketch of the American branch of the family of de Beelen. Reading, PA: C.F. Haage, 1894.

Polasky, Janet L. Revolution in Brussels 1787-1793. Brussels: Academie Royale de Belgique, 1987.

Schlitter, Hanns. Die Berichte des ersten Agenten Österreichs in den Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika. Vienna: F. Tempsky, 1891.

Singerton, Jonathan. “175 Years or 235 Years of Austrian-American Relations? Reflections and Repercussions for the Modern Day.” In Joshua Parker and Ralph Poole, eds., Austria and America: 20th-Century Cross-Cultural Connections. Zurich: Litt Verlag, 2017: 13-30.

Weber, Klaus. “Linen, Silver, Slaves, and Coffee: A Spatial Approach to Central Europe’s Entanglement with the Atlantic Economy.” Cultural & History Digital Journal 4, No.2 (December, 2015): 1-16.

van Houtte, Herbert. “Contribution à l’histoire commercial des Etats de l’empereur Joseph II,” Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte 8, No. 2/3 (1910): 350-393.

Archival Sources:

Haus-Hof-und-Staatsarchiv, Vienna, Staatskanzlei, Belgien, DDB Rot, K. 182a-e.

Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Beelen Family Papers.

Learn More:

More detailed analysis: https://jonathansingerton.com/2017/10/12/the-beelen-bertholf-papers/

On consular reports more generally: https://blog.uvm.edu/nphelps/a-brief-introduction-to-the-us-consular-service/

A letter from the Habsburg ambassador to Benjamin Franklin regarding Beelen: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-41-02-0218