The Cleveland Cultural Gardens and the Peoples of Former Austria-Hungary in the 1930s

By Kristina Poznan

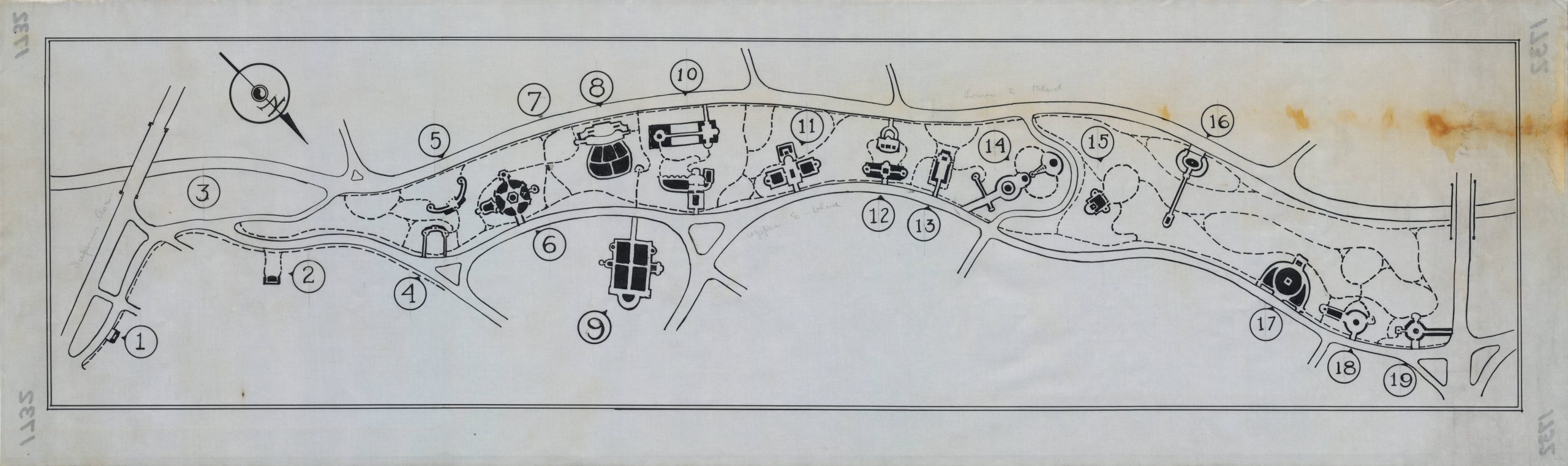

Within its 276 acres, Rockefeller Park hosts a unique collection of public gardens, 33 in all, each a celebration of an immigrant group settled in Ohio. Of these, several represent migrants from the lands of the former Habsburg Empire. Its goals were visionary. “Cleveland Cultural Gardens are accomplishing in their community the same thing that the League of Nations is trying to do for the world,” League representative Guillame Swiss proclaimed in 1935. The Cultural Gardens offered local ethnic communities the opportunity to design gardens to celebrate their culture through statues to “poets and other cultural leaders.” The Cleveland City Council had authorized the creation of an expanded series of culturally driven landscape features in Rockefeller Park in 1927, many of which opened in the 1930s.[1] Local committees handled many of the preparations with critical assistance from the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration for execution of the infrastructure. As historian Mark Tebeau explains, “The gardens “reveal the history of immigration to, and migration within, the United States.”[2]

Among the peoples of the Eastern Europe after the Great War, Cleveland’s Cultural Gardens apportioned the park’s acreage by different cultures, rather than countries. In contrast, at the University of Pittsburgh, for example, The Cathedral of Learning housed the “Nationality Classrooms” with representation by official state entities: it featured a single Czechoslovak classroom to recognize the country of Czechoslovakia, whereas Rockefeller Park featured separate Czech, Slovak, Rusin, German, and Hebrew gardens. The immigrant Clevelanders with some connection to former Austria-Hungary that were represented with gardens included the city’s Croatian, Czech, German, Hebrew, Hungarian, Italian, Polish, Romanian, Rusin, Serbian, Slovak, Slovenian, and Ukrainian communities. The Hebrew and German gardens were built first, both in the late 1920s. A Slovak Garden was dedicated in 1932, a separate Czech one in 1935, and similarly, a Rusin Garden in 1939. “It was no mistake,” Tebeu explains, “that the Czech, Slovak, and Rusin gardens were arrayed themselves across a boundary street from the contiguous German and Hungarian gardens, suggesting how powerfully old cultural conflicts were felt.” The physical division of the Austro-Hungarian old guard affirmed the recent wartime conflicts. Indeed, “The gardens often . . . subverted the message of unity and reflected ethnic tensions in Europe and Cleveland,” he continues. [3] Despite this political messaging, the gardens strove to exhibit fraternity and peace amid the diversity. The Cultural Gardens’ “One World Day” festival takes place every August.

The descriptor of the gardens as cultural was intentional, attempting to steer clear of political controversies. As historian John Bodnar has explained, the impulse for the creation of the gardens “promote[d] effects towards international peace and brotherhood” and “favored notions of pluralism and tolerance over aggressive Americanism” (as well as aggressive European nationalisms). Statuary or other elements that were “political or military in nature” were prohibited from the gardens; instead, figures selected for elevation were recognized for their poetic, musical, or literary accomplishments.[4] The German Garden features the likes of Goethe and Schiller, Bach and Beethoven, and the Hungarian Garden features most prominently Franz Liszt. This was not the place for political revolutionaries like Lajos/Louis Kossuth of the 1848 Revolution, who visited Cleveland in 1853 and whose statue stands less than two miles away in University Circle. Cultural icons, rather than explicitly political ones, were meant to peaceably recognize the origins of Clevelanders from across the Atlantic (and later elsewhere).[5] Although most of the features were built purposely for the gardens, some repurposing did occur; most notably, a fountain dedicated to German pedagogue Friedrich Froebel was relocated from Salzburg.[6]

The emphasis on grand cultural figureheads with whom migrants merely shared a homeland meant, however, that the gardens only modestly reflected immigrant Cleveland itself. Missing from the gardens are the “ordinary people—immigrant pioneers—who had created that great migration streams to America in the first place and who had lived and toiled in Cleveland’s ethnic neighborhoods.”[7] The few exceptions are noteworthy: local artist Frank Jirouch’s frieze for the Czech garden depicting the arrival of Bohemians in America is one of the few visuals of non-elite immigrant life.[8] Of the two busts in the Slovak Garden, one is of Catholic priest Stefan Furdek, who ministered in Cleveland from 1882 until his death in 1915 and founded many of the city’s Catholic Czech-, Slovak-, and Hungarian-language institutions at the turn of the century.[9] Transatlantic connections are more evident in the programming at many of the gardens, if not the majority of the permanent statuary. Throughout the latter half of the 20th century several foreign dignitaries have visited the Gardens, and to this day the Gardens host events that continue to foster connections between Austria-Hungary’s successor states and Cleveland’s Central and Eastern European communities, from Hungarian choir concerts with performers from overseas to Italian film nights.

After decades of migration and years of world war, with hundred of thousands of migrants from the former territory of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the United States, most Americans still had little understanding of the peoples of Eastern Europe. The categories of race, ethnicity, nationality, mother tongue, and other markers were all fluid and fraught, and the map of Europe changed dramatically in the World War I era – who could fault all Americans for confusing Hungarians and Bulgarians, Slovaks and Slovenes? In interwar northeastern Ohio, at least, the cultural pride on display in Rockefeller Park illustrated the diversity of Clevelanders. And it continues to be an evolving story. The Yugoslav garden, dedicated in 1938, was refashioned as the Slovenian garden in 1991 and a new Serbian garden added in 2008.

An Austrian Garden may seem conspicuously absent to readers of this blog. In many American places that German-speaking Austrian immigrants settled, they joined German organizations, as in the case of Cleveland’s German Garden. That said, migrants from Gottschee County in Carniola (today in Slovenia) were so numerous that they founded the First Austrian Mutual Aid Society, or Erster Österreichischer Unterstützungs Verein (E.O.U.V.), in 1889, and later the German-Austrian Mutual Aid Society, or Deutsche Österreichischer Unterstützungs Verein (D.O.U.V.), which merged in 1955. [10] In the 1980s they purchased a large plot in Novelty, Ohio, to the east of Cleveland, home of the 56-acre Gottscheer Park.[11] Cleveland was also home to societies of Danube Swabians, previously headquartered at Banater Hall (c. 1925) within the city and now at Lenau Park in nearby Olmsted Falls.[12] Greater Cleveland has no shortage of physical spaces devoted to its Austro-Hungarian roots to visit if you find yourself in northeast Ohio.

Author Biography:

Kristina E. Poznan, PhD, is a scholar of American immigration and foreign relations history. Her work examines the relationship between transatlantic migration, migrant identities, and separatist nationalism in the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the context of migration to the United States. From 2017 to 2019 she was editor of Journal of Austrian-American History, sponsored by the Botstiber Institute for Austrian-American Studies and published by Penn State University Press.

Further Reading:

Bodnar, John. “Public Memory in an American City: Commemoration in Cleveland.” In Commemorations: The Politics of National Identity, edited by John R. Gillis, 74-89. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Lederer, Clara. Their Paths are Peace: The Story of the Cleveland Cultural Gardens. Cleveland: Cleveland Cultural Garden Federation, 1954.

Martin, Sean. Cleveland’s Land of Promise: Rockefeller Park and the Jewish Community. Cleveland, OH: Case Western Reserve University, 2010.

Tebeau, Mark T. “Sculpted Landscapes: Art & Place in Cleveland’s Cultural Gardens, 1916-2006,” Journal of Social History 44 no. 2 (2010): 324-350.

Tebeau, Mark T. “Sculpted Places: Identity, Community, and the Cleveland Cultural Gardens.” https://academic.csuohio.edu/tebeaum/courses/euclid/Tebeau_Gardens.pdf

Notes

[1] Lederer, Their Paths are Peace, 32, 30.

[2] https://academic.csuohio.edu/clevelandhistory/culturalgardens/

[3] Tebeau, “Sculpted Places: Identity, Community, and the Cleveland Cultural Gardens,” 7.

[4] Bodnar, “Public Memory in an American City,” 81-84.

[5] Tebeau’s “Scultped Landscapes” documents many instances in which political disputes broke out within and between committees nevertheless.

[6] https://germanculturalgarden.org/

[7] Bodnar, “Public Memory in an American City,” 82.

[8] https://www.clevelandculturalgardens.org/gardens/czech-garden/

[9] https://case.edu/ech/articles/f/furdek-stephan

[10] https://www.eouv.com/about/history

[11] https://www.eouv.com/about/park

[12] https://cplorg.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4014coll18/id/1455/ and

http://www.donauschwabencleveland.com/