Rosa Wien: Gay Rights, Schlager and Self-Exile: 1918-1938

By Casey J. Hayes

So…What comes to mind when you hear the word “Cabaret”? Perhaps…Liza Minelli? Yet, however historically accurate this depiction of the 1920s Weimar Berlin cabaret scene may be (I doubt they had Liza or Bob Fosse,) it was a more reserved cabaret culture that developed within the Austrian capital; more quick conversation, jokes, political statements, and sentimental chansons; less drag queens and spectacle. It would have, I believe, looked much more accessible to the conservative Viennese and less like the pages from a Christopher Isherwood novel. Still, there are many historical yet little-known events that played out at the intersection of the struggle for civil rights for western society’s gay communities, the National Socialist’s persecution of homosexuals, and the fate of some of Europe’s greatest performing artists self-exiled in Vienna. The wildly hedonistic world of German-speaking Cabaret would be the backdrop for a collision which resulted in the ultimate elimination of the art of the “Kleinkunstbühne” throughout Central Europe.

Whether you were in Berlin or Vienna or New York City during the years leading up to the “Anschluß” of Austria into the Third Reich, one thing was certain; cabaret culture, based around the hit songs, or “Schlager” of the period, was not only a popular form of entertainment for the dominant, heterosexual culture, but an extension of the sexual sub-cultures of the cities, particularly the LGBTQ/Gender Fluid communities.

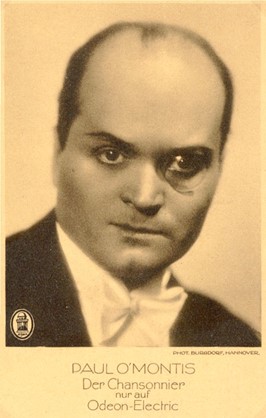

I approach the homosexual and gender fluid culture of Vienna from 1918 until 1938 as a door which opens and then closes for non-binary sexual tolerance. Vienna’s unique status as both Austrian state and controversial Socialist enclave during the early 20th Century made it a home for those seeking a sympathetic society, paralleling New York City’s role within the United States. Through information gleaned from the popular music and musicians of the period, I have been working to detail the change in societal opinion toward the gay male in Vienna, change resulting from swift and efficient Nazi propaganda and the expansion of Paragraph 175, which supplanted Austria’s Paragraph 129 after March of 1938. It was this shift of societal tolerance which led many of Europe’s gay musicians and performers living in Vienna to flee the city which at one time welcomed them with open arms. I examine these issues through the life and music of cabaret performer Paul O’Montis, a homosexual, Protestant performer, composer, artist, and radio/recording star who was at the height of his career upon the rise of the National Socialists and his self-exile to Vienna.

Viennese Cabaret was a smaller extension of a larger German-speaking cabaret culture which included Berlin and Prague. Although based largely in Berlin, the artists would frequently move from one city to the next, creating a circuit of performers. Berlin, due to its high wages and less restrictive social norms, would take the lead on developing a wildly diverse cabaret culture inclusive of Jews, such as Max Ehrlich and Willy Rosen, Gays, such as Paul O’Montis and Teddy Sinclair, Lesbians such as Claire Waldoff and Anita Berber as well as Transvestites and other Gender Fluid performers, such as Marlene Dietrich and Wilhelm Bendow. Performers outside the mainstream constructs of gender found Vienna gracious and accepting, yet with a reservation that insisted upon keeping the activities on the stage less vivacious or scandalous than Weimar Berlin.

The sudden growth of Viennese Cabaret can be traced back to the Vienna Theater Act of 1930, in addition to a wave of emigration from Germany following 1933. The 1930 Theater Act differentiated between events that “only have to be registered with the authorities” and those “that require an official permit (license).” The lesser registration requirement, which also came with significant tax relief, applied to “all theatrical and variety performances if the [venue] has a capacity of less than 50 people.” Thus, to avoid the high cost, long wait and scrutiny of a permit, many venues chose to limit their audience size to 49 spectators, making the new “Theater für 49” and Cabaret the most popular form of entertainment within the city.

With the rise of the National Socialists in Germany, many Weimar Berlin performers sought refuge in Austria. The sudden oversupply of talent created a heyday for Cabaret. A quote from Hilde Haider-Pregler’s Exilland Österreich states:

Under Goebbels’ and Rosenberg’s leadership, Germany has started its journey back to primitivity. This homeless art is anxious, looking for a new home… And this new home must be found in Austria. Austria is today the mobile depot of German culture. From Austria, our German brothers should pick up this culture if they long for it.

Yet, in April of 1934, the Austrian parliament was brought together by Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss and accepted an authoritarian constitution. Elected assemblies disappeared and human rights, guaranteed under the previous democratic constitution, were nullified as the word “Republic” was removed from the official name of the country, becoming the “Federal State of Austria.” This new Austro-fascist government required that all artistic performers in Vienna possess a permit to practice their profession in one of the theatres subject to Austrian rights restrictions. These restrictions meant membership in one of three organizations, all of which denied entry to performers with undesirable “racial” or “political” affiliations. An unforeseen consequence was that this accelerated the growth of Viennese Cabaret. Vienna’s finest performers had no choice but to play in a “Theater für 49” or in one of the smaller Viennese Cabarets which required no license. By 1938, no fewer than 25 of these “Kleinkunstbühnen” were playing in Vienna, where many “Schlager” or “Hit Songs,” written to bring the German-speaking LGBTQ community together, were performed to an eager audience. Examining just a few select “Schlager” can illuminate the socio-political status of the LGBTQ community in Central Europe by gleaning information from the lyrics and the performer.

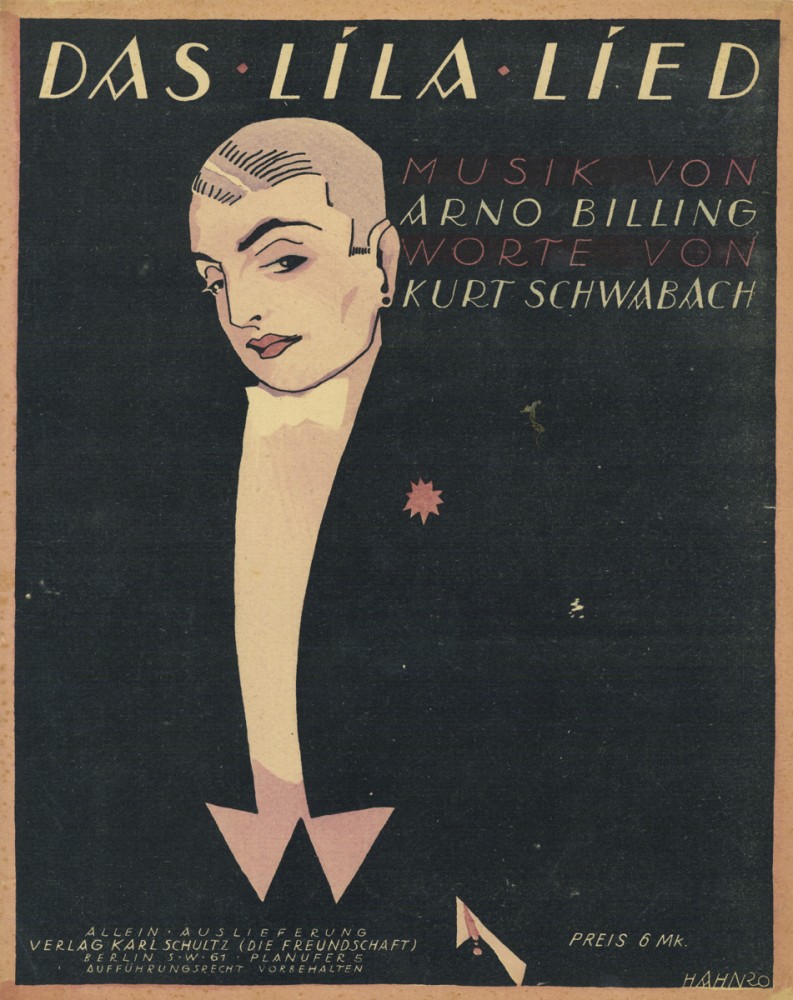

Sheet Music Cover for “Das Lila Lied”

In the case of the first LGBTQ Anthem, “Das Lila Lied” or “The Lavender Song,” the direct and poignant lyrics speak to the nature of what it meant to be “Anders als die Andern” or “Different from the Others,” a phrase taken from the first film addressing the topic of homosexuality. Written by one of the most prolific and popular composers of Schlager at the time, Kurt Schwabach, with lyrics by Mischa Spoliansky (under the pseudonym Arno Billig), “Das Lila Lied” was dedicated to Magnus Hirschfeld and his “Institut für Sexualwissenschaft,” which pioneered gay rights as early as 1919 from his institutes in Berlin and Vienna. “Das Lila Lied” was written in 1920 and premiered in 1921 with lyrics that articulated a gay community’s disgust with the way they were treated by the dominant culture. Regardless of the fact this was an anthem for the gay community, this song became among Kurt Schwabach’s first hits with the public and here’s how…

When the song was recorded by the Marek Orchestra, it was done without the vocal track. It became popular as a dance number with the general public, most completely oblivious to the lyrics. It would only be through the purchase of the sheet music that the lyrics would be revealed. Reflective of the general malaise of Weimar Germany, the song would take off in the large urban areas and be dismissed by the rural masses. The cabaret scholar Alan Lareau notes:

“Das Lila Lied” addresses its audience with a frontal assault on traditional notions of morality and “culture,” arguing in the first-person plural that homosexuals are intelligent, good, playful, and loving people and that narrow-minded Philistines must learn to accept and appreciate them.

However, there were many performers who would record lyrics that were meant to shock or offend the general public. The freshly minted Marlene Dietrich would sing a duet with the more-established Margo Lyon declaring that being with a woman is a vast improvement over a man titled “Wenn die beste Freundin mit der besten Freundin.” In it, there is wonderful spoken dialogue which deemphasizes the need for a man when one has her best girlfriend! Yet, there are some Schlager that are further emphasized by who sings them and rare was the performer who could match Paul O’Montis. Ralph Raber notes:

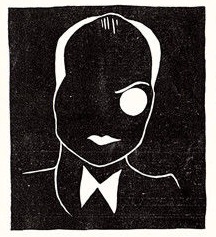

The Chanson singer Paul O’Montis, the Dandy who was a touch “Effeminate” with leggings and tie – at times even wearing “Pumps,” strolled lightly through everyday life, flirting with men and women at the same time. He remained completely superficial, non-committal and self-loving – but none the less uncertain…frequently hiding his true feelings, choosing instead to play the part of the aloof star; suspended in a world of music, art, and conflict…

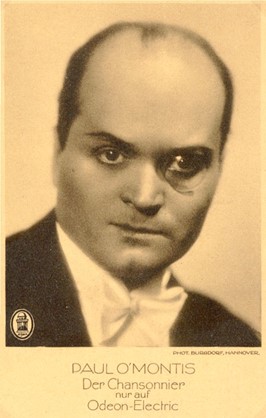

Paul O’Montis Cigarette Card

O’Montis lived his homosexuality openly, whether in public or on the stage. A German citizen born in Budapest in 1894, O’Montis was a talented singer, recording artist, even a book and sheet music cover illustrator. While living in Berlin, he performed at the Charlott-casino as well as made appearances in “Cafe Meran,” “Florida,” and the well-known nightclub “Simpl.” However, it was when he became acquainted with the writer and lecturer Frank Günther, who finally brought him into the world of Weimar Cabaret that he began his ascent. Together with Blandine Ebinger and Valeska Gert, he was on stage in the Friedrich Hollaender revue “Laterna Magica” in February 1926; a break-through performance which launched his performing career.

In the reviews, he is now almost “cheered.” His sophisticated – caricatural couplets, puns and ambiguities as well as the open coquetry (with a lot of self – irony) about his homosexuality on the stage are very well received by the audience.

By the end of 1933 he didn’t shock anyone with his effeminate appearance; he was praised in all newspaper reviews, even the Westdeutscher Beobachter, a daily newspaper in Cologne which was a well-documented mouthpiece for the National Socialists, published an extensive “portrait of the artist.” The homosexuality of O’Montis is evidently overlooked, and he even refers to himself as being “Aryan.” Whether those were his exact words or a creation by the article’s author remains unknown.

In his Schlager “Was hast Du für Gefühle Moriz?,” written in 1927 with text written by Fritz Löhner-Beda and music by Richard Fall, we can see the double entendre that becomes characteristic of an O’Montis performance. The playful ambiguity, the veiled yet open secret, made his acts quite intriguing: “What are your feelings, Moritz?” he coyly asks of the stylish but devilishly evasive stud who has all of Berlin at his feet. “You don’t say yes, you don’ t say no-there’s something funny going on here,” people grumble. And when he pays a visit to the aging starlet Frau Camilla, she becomes quite concerned when he fails to succumb to her charms, however explicitly they may be offered up to him. So, is Moriz … or is he not …? Beda and O’Montis play with this question through gossip over Moriz’s alleged female affairs of which, in the end, it is noted with a smile that he flirts only with the male porters.

O’Montis was a beacon for the German-speaking LGBTQ community. His effeminate nature and open homosexuality not only made him an admired figure within the gay and lesbian subculture, but also an open target for the Nazis. One notable performance set the stage for O’Montis’ future within the Germany of the National Socialists. During Berlin’s “Scala” Festival between October 1 and October 31, 1933, O’Montis, with fellow performers Otto Wallburg, Maria Solveg, and Werner Finck were observed by Nazi Minister for Propaganda Joseph Goebbels. Following the performance, Goebbels is said to have referred to the evening as the “Festival of Disreputable Figures.”

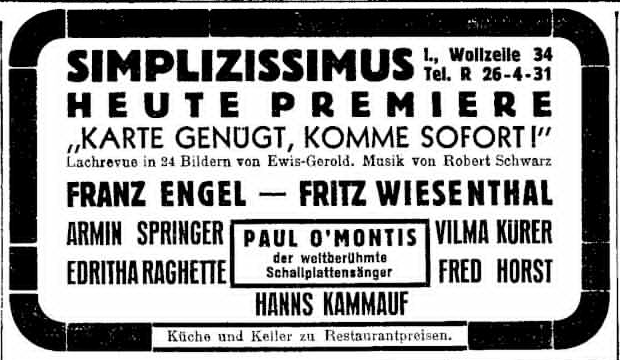

O’Montis fled to Vienna in 1934 and in 1935 received an official ban on performing in Germany, a ban that affected all “degenerate” music and performers. In Vienna, he continued the occasional appearances at the Volkstheater as well as daily performances at the “Kaiser-Bar” at Krugerstraße 3 in the 1st District beginning on March 18, 1936.

After the “Anschluß,” O’Montis fled to Czechoslovakia, where he was arrested in Prague on June 27, 1939. He passed through several internment camps, first in Zagreb, then to Lodz. Finally, in June 1940, he arrived at the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp, where he was housed in isolation block 35, a familiar location for imprisoned homosexuals. O’Montis was beaten to death by the Kapo on July 17, 1940, a fact contrary to the original Gestapo file stating that he died from suicide, sadly indicative of many of the country’s great cabaret artists. Sadder still is that much of the music, life, and legacy of performers such as O’Montis has been lost to time. The few researchers into the musical aspects of this period are still uncovering gem after gem of lost works and recordings.

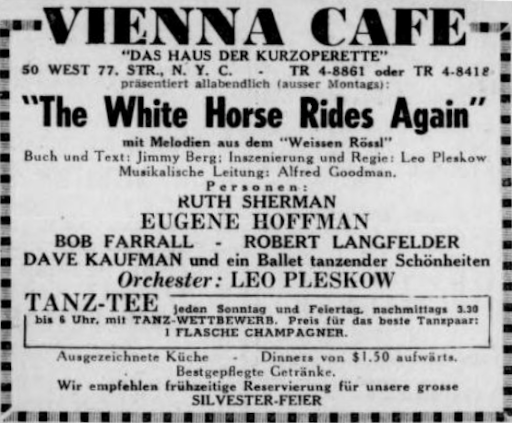

Performers who were fortunate enough to manage a visa to the United States prior to 1938 inevitably found themselves in New York, using their Viennese cabaret music to rebuild their community in Manhattan.

Jimmy Berg Photo: 1930s; Jimmy Berg Collection, Austrian Exile Library in the Literaturhaus Vienna, © Trude Berg

On the Upper West Side, the multi-talented performer Jimmy Berg opened a performance space on West 70th St. that focused upon the traditional chanson-style Cabaret which encouraged reminiscing and community-building. Berg left Berlin in 1933 for Vienna, where he opened the “Café ABC” with Jura Soyfer in 1935. He would ultimately leave Vienna for the United States after the “Anschluß” and his Cabaret “Die Arche” became the cornerstone of the exiled Viennese cabaret community in New York through the 1950s.

Many cabaret artists who made New York home organized themselves into the Refugee Artists Group, or RAG, with experienced Broadway managers and producers. A theater was made available to them rent-free; the technical staff was satisfied with symbolic payment and all performers received the same fee. Any profits would be used to support Viennese theater people who came to America as refugees. On June 20, 1939, their show From Vienna was staged for the first time, a cabaret revue which mixed tried and tested Viennese Schlager with current American skits and songs. The press was kind and positive: “A great group that has something unique to offer to New York theater audiences,” wrote Willela Waldorf (New York Post, June 21, 1939). Theater critic Brooks Atkinson went a little deeper into the basics of the performance: “What do we expect from refugees?” He asked.

Do we expect them to be scared, shy, or submissive? Do we expect that they left their personality at home, under the rubble of a damned country? Whatever we expect, with this group of actors we experience the charisma of good people who do what they enjoy. Their smile is attractive, their talent full of sensitivity. It is shocking to realize that such people can be refugees from part of the civilized world. Because they represent the charm and delight of civilized life. But they are now among friends. (New York Times, June 21, 1939).

During June and July 1939, they gave 79 performances, coming back in February 1940 with a second edition of their revue. However, the group soon disbanded, mainly because the younger men were inducted into American military service. As their new country drew further into the conflict, the mood of exile Cabaret began to change. Fewer and fewer Viennese would grace the stage, being replaced by their American counterparts.

In the years before the USA entered the war, German-language Cabaret only had a chance in the small New York artist cafes: the “Cafe Vienna,” the “Broadway Fiaker,” “Lublo’s Palmgarten,” or the “Old Europe”…At first the German-speaking artists dominated, then gradually more and more American names appeared. A very peculiar, sometimes Viennese, cabaret scene developed. Nevertheless, the protagonists made their way through badly. The failure resulted mainly from the fact that a large number of the Jewish emigrants no longer wanted to speak German. Most of the non-Jewish German-speaking population, the “Bundists” from Yorkville, sympathized with the National Socialists. These German-Americans wanted nothing to do with a cabaret operated by emigrants. (Trapp, Frithjof Handbuch des deutschsprachigen Exiltheaters 1933-45)

As most things Viennese within the United States were finding it necessary to develop a less-public profile, the exile community’s cabaret would ultimately be assimilated into the dominant culture, creating a financially untenable situation for those performers who attempted to keep the small stage art form going. Thumser writes that:

There were plenty of opportunities to perform, but the net income was likely to have been marginal, and most of the artists had to pursue bread-and-butter jobs. Jimmy Berg worked in a tar factory on weekdays; the comedian Armin Berg was forced to earn money in addition to his appearances by moving from house to house with small items such as pencils and trying to sell them. (Thumser, Regina, “From Vienna: Exilkabarett in New York 1938 bis 1950”)

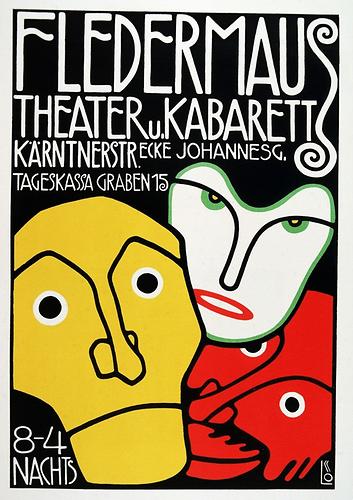

The larger names that constituted Viennese Cabaret, such as Robert Stolz, Paul Abraham, Oscar Strauss, and Emmerich Kalman quickly set their sights on greater venues that would draw larger crowds and incomes. Robert Stolz, the darling of Viennese operetta during the Silver Age, made his way from New York to Hollywood in 1941. He was nominated for two Academy Awards, one for Best Song (Waltzing in the Clouds, 1941) and one for Best Score (It Happened Tomorrow – 1945) and returned to Vienna in 1946 where he died in 1975. Stolz’s colleagues Abraham, Strauss, and Kalman, following successes in both New York and Hollywood, returned to Europe following the end of the war. Armin Berg, along with many of the former Viennese performers in exile would find their way back to their homeland only to find that the “Kleinkunstbühne” once peppered throughout Vienna were gone. The remnants of a once vibrant cabaret scene in the Austrian capital can be found at the “Kabarett Simplizissimus” at Wollzeile 36 and “Cabaret Fledermaus” at Spiegelgasse 2, both of which are located in the 1st District, paying homage to their historic namesakes from a time when Viennese cabaret was both entertaining and an important part of the political dialogue during the years leading up to the “Anschluß.”

Cabaret performers identified as non-binary would experience a variety of obstacles. Some, such as O’Montis, would suffer the fate of so many gay men during the Holocaust. Others, such as Wilhelm Bendow, were investigated and banned from the stage for alleged homosexual ties but did not face harsh punishment due to influential friends in the new government. Lesbians such as Claire Waldoff, while not deemed criminal under the Reich, would leave the stage and remain in Germany, where their careers would fade upon their rejection from the Reichskulturkammer. Whereas Dietrich made a successful transition to the American movie industry, few LGBTQ performers shared such good fortune.

In conclusion, the social constructs of the 1920’s and early 1930’s helped propel Viennese “Kabarettisten” to new heights of popularity, whose performances and recordings helped to bring together a communal sub-culture during a time when exterior forces, backed by strict anti-homosexual legal frameworks, had few means in which to connect to the dominant culture. Music and musicians of the time, through song lyrics and performance style, aided in building a sub-culture of acceptance for the LGBTQ community of Central Europe. Upon the rise of the National Socialists, a vibrant transplant community of cabaret performers attempted, with mixed success, to reconstruct their community in Vienna and New York City as they were forced to leave the familiar for a world that promptly closed the doors on tolerance and understanding.

Author Biography

Dr. Casey J. Hayes is a Professor and Chair of the Music Department at Franklin College, in Franklin, IN. He is a 2021 Fulbright-Botstiber Scholar to Vienna, where he teaches a course on his research subject at the Institut für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien. He has presented at the Fulbright Strobl Conference on Austrian American Studies and is currently working with the United States Embassy in Vienna to construct presentations, talks and outreach projects with the city’s LGBTQ community during the June Pride month of 2021.

Further Reading

Jarka, Horst, Jimmy Berg, Von der Ringstraße zur 72nd Street, Volume 17 Austrian Culture, Peter Lang Publishing, New York, 1996

Klosch, Christian, Thumser, Regina, From Vienna: Exilkabarett in New York 1938 bis 1950, Picus Veerlag Wien, 2002

Raber, Jörg Ralf, Wir sind wie wir sind, Männerschwarm Verlag, Hamburg, 2010

Seeber, Ursula (Hg.), Asyl Wider Willen: Exil in Österreich 1933-1938, Picus Verlag Wien, 2003

Published on Tuesday, June 15, 2021.