External view of NARA II, Spring 2023

Source: Duncan Bare

Researching US Intelligence Organizations in Austria at the End of the Second World War

By Duncan Bare

“While much is already known about what US intelligence did in Austria between 1945 and 1955, relatively little has been written to date about their structure(s) or personnel, except to add ‘flavor’ and depth to stories of their operational exploits or specific projects.“

My Project

“America’s Eyes On and In Central Europe: A Reexamination of SSU and CIG in Austria” examines US intelligence agencies in postwar and Cold War Austria, not from an operational or results-oriented perspective, but rather, an interpersonal and organizational, systems-based one.

In suggesting this project for the 2022/2023 grant period to the Botstiber Institute for Austrian American Studies, I sought answers for questions such as: How did the various US intelligence organizations of the postwar period (Office of Strategic Services, OSS; Strategic Services Unit, SSU; and Central Intelligence Group, CIG) establish themselves in Austria? How did their personnel interact with one another? Who set targeting priorities, when, and why? Who were their “customers”? How was their intelligence “product” disseminated both in Austria (the field) and to headquarters in Washington (departmental)? What sort of value did field-based and departmental customers assign to this intelligence? Were there any feedback loops, and if so, did they lead to improvements or changes in process and methodology ‘on the ground’?

While much is already known about what US intelligence did in Austria between 1945 and 1955, relatively little has been written to date about their structure(s) or personnel, except to add ‘flavor’ and depth to stories of their operational exploits or specific projects. [1] In some way, the task I set myself was to write organizational ‘biographies’ of OSS, SSU, and CIG in Austria. To accomplish this as accurately and comprehensively as possible, I would also need to reconstruct their organizational ‘family trees’, with branches stretching back to Washington.

Despite the abundance of secondary sources pertaining to operations and general history, I quickly realized that archival documentation would provide this project’s backbone. The ‘mundane’ administrative reports I would need have little in common with the flashy and debonaire world of James Bond, Jason Bourne, Jack Ryan (why do all fictional spies have names that start with ‘J’?) or even, the smoky, back-alley noir of The Third Man. Instead, if a fictional analogy is helpful, my work would piece together archival snippets and information like George Smiley in John le Carré’s masterful Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. [2]

Here too, I wanted to answer several questions: Who was where, when, and for how long? What position did they hold? What were their formal responsibilities? What did they do? Did they enjoy it, find it tedious? Were they rated highly by their immediate supervisors? Did they reference this work in later memoirs, reports, or other writings? If so, what did they have to say about it?

Getting Started

I am extremely lucky to have been able to conduct research at the National Archives and Records Administration, building II (NARA II) for my undergraduate and graduate theses. For these, I gathered some 12,000+ photographs and scans of documents, which I had roughly transcribed and annotated while writing my theses. By 2020, my annotations required a second look, so I began to re-transcribe and evaluate all of the digital scans I had, greatly increasing the amount of fully text-searchable material at my disposal. In addition, Prof. Siegfried Beer generously allowed me access to this own miniature archive of US intelligence documentation. Unfortunately, I was then unaware of advances in optical character recognition (OCR) technology and relied instead on manual transcription with a second monitor.

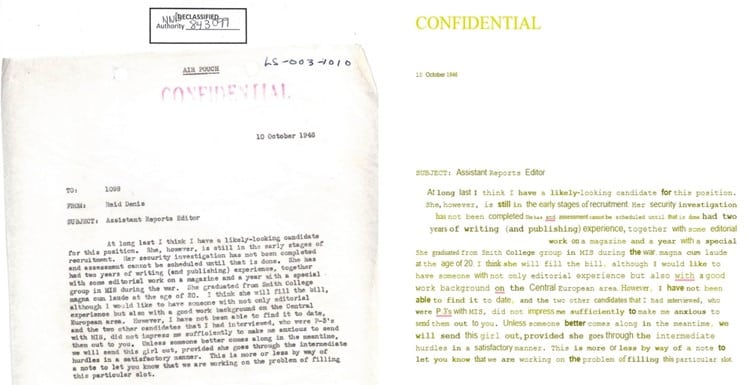

On the left, a document scanned at NARA II; on the right, the document after undergoing OCR with Google Docs. Although some data is missing (date, to/from lines, etc.) it has been transcribed above and below the main body text and was correctly read. Formatting the text on the right takes considerably less time than transcribing the entire document on the left would. Source: Author’s scans, NARA II.

This brings me to my first ‘hint’ or ‘tip’ about archival research: Use OCR whenever possible. To easily try this out, create a small PDF of the papers you wish to make text-searchable, upload it to Google Drive, and open it as a Google Doc. Once the Google Doc loads, you’ll be able to copy and paste the text that was read from your documents, which you can then compare side-by-side with the original and revise. You will need to correct spelling mistakes and delete characters that are not important or relevant, however, this takes much less time than transcribing those same documents manually.

By rechecking the archival documentation, I had, I was able to plan future archival visits, knew what I needed, and where potentially interesting documents might be located that I had missed earlier. As I had transcribed them manually, I could also recall names, places, and even specific documents.

In this blog post, I would like to discuss the methods I have developed while researching at NARA II rather than the results of my work (which are already available, in part, in the Journal of Austrian-American History [3])

Understand Declassification and Its Limitations [4]

The majority of declassified OSS, SSU, and CIG documents at NARA II can be found in Record Group 226. Other important and relevant record groups for US intelligence in Austria during and after the Second World War include 59 (State Department), 242 (Foreign Records Seized), 263 (CIA), 319 (Army Staff), and 331 (Allied Operational and Occupation Headquarters), among many others. Thanks to the efforts of the Interagency Working Group (IWG), formed pursuant to the Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act (NWCDA, 1998), most OSS and SSU records are believed to be fully declassified.

However, there are exceptions. In many cases, these are only realized when one looks carefully and holistically at the available documents compared to what they describe or what is absent.

In the case of SSU Austria for example, the last monthly progress report that the author has found in more than 10 years of searching at NARA II is for May 1946 and notes that the format will change the next month (June, written in July 1946) pending the transition to a new organization per Washington directives.[5]

I have never located June-October 1946 SSU Austria progress reports (only those of certain branches, such as SCI/A, or the ‘informal’ ones sent by the mission’s chief, Alfred C. Ulmer to his supervisor, Richard M. Helms, in Washington, or vice versa). Contemporary administrative memos and correspondence are in the relevant folders along with cross-references to those progress reports, however, signifying that these progress reports do exist.[6]

What’s more, all documentation ceases abruptly after October 19, 1946, which is taken as the ‘end of SSU’, even though that organization was officially dissolved only in June 1947.[7] Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude, after combing through all relevant files in RG 226, both among those originally released in the 1970s-1980s, and those that came with the NWCDA, that progress reports for SSU Austria are complete, in a literal, rather than contextual sense: Since SSU Austria ‘ceased to exist’ by the middle of June 1946, progress reports produced by its successor (even if different in name only) are likely not declassified as they are seen as part of the institutional legacy of CIG (and by extension, CIA) rather than OSS and SSU.

The underlying logic is confusing, however, declassified CIA historical office reports, get to the point rather quickly:

“SSU was liquidated as an operating unit on 19 October 1946 with the Central Intelligence Group (CIG) in due course assuming most of its functions. However, SSU continues to exist as an entity which is considered an integral part of CIA, largely for the purpose of replying to specific requests for certain types of administrative information in the OSS records.” [8]

Prior to the NWCDA, large numbers of OSS and SSU records remained classified based on the above argument. [9] However, in the aftermath of the NWCDA the IWG engaged in rather intense bureaucratic conflict with CIA over the declassification of these same records. The compromise that was eventually reached (and which the IWG was not entirely satisfied with apparently) saw the ‘new’ cut-off moved up to any organization deemed part of the CIA”s institutional heritage. Even though CIG/OSO was the direct successor to SSU, it was considered to be the Agency’s predecessor, and therefore, its records appear to be almost entirely classified. [10]

This makes for interesting chronological discrepancies, such as the presence of counterintelligence monthly progress reports from SSU Austria for the summer months of 1946. In light of the amalgamation of counterintelligence and positive intelligence in June 1946 within SSU, and Ulmer’s dual responsibility for both in the summer of 1946, it is telling that the positive intelligence progress reports are unavailable, while those of the counterintelligence branch are. But here too, time is eventually on the side of classification, as the cut-off date of October 19, 1946 is fairly strictly adhered to in RG 226, apart from those reports that were only received after that date (but filed on or before it).

In sum, when dealing with OSS and its successors, a general rule might look something like this:

OSS records are nearly entirely declassified while those of SSU are largely available up to the middle of June 1946, after which, there are gaps, with a ‘wall’ in declassification from October 19, 1946 on. [11]

Use the “Finding Aids”

Besides having realistic expectations, researchers should make the most effective use of finding aids, including digital ones. RG 226 is widely seen as one of the most thoroughly and comprehensively described holdings at NARA II.

Digital finding aids for RG 226 that can be used prior to stepping foot on site include NARA’s website, and the National Archives Catalog (https://catalog.archives.gov/). While the last of these can be unwieldy at times, once understood, it can prove extremely helpful in retrospectively understanding how files for a particular organization or institution are maintained, and, upon successive trips, to triangulate important or sought after files.

Highly detailed digital finding aids for Entries 210-224 of RG 226, the so-called “Sources and Methods” files, which represent that material which was withdrawn by the CIA from the original releases of OSS documents in the 1970s-1990s on various national security exemptions, are available at: https://www.archives.gov/iwg/declassified-records/rg-226-oss/sources-and-methods-files.html.

On site, there are many more ‘analogue’ finding aids, especially for OSS documentation that was released earlier (roughly one and a half bookcases full). These can be used to effectively locate records with a variety of different approaches, such as based on their subject, the office or station they originated from, or even their branch within OSS. Folder lists, many created in the 1980s and 1990s by volunteers who had served with OSS or its successors, provide detailed insight into box contents, and the keywords they use are cross-referenced in larger, more voluminous aids.

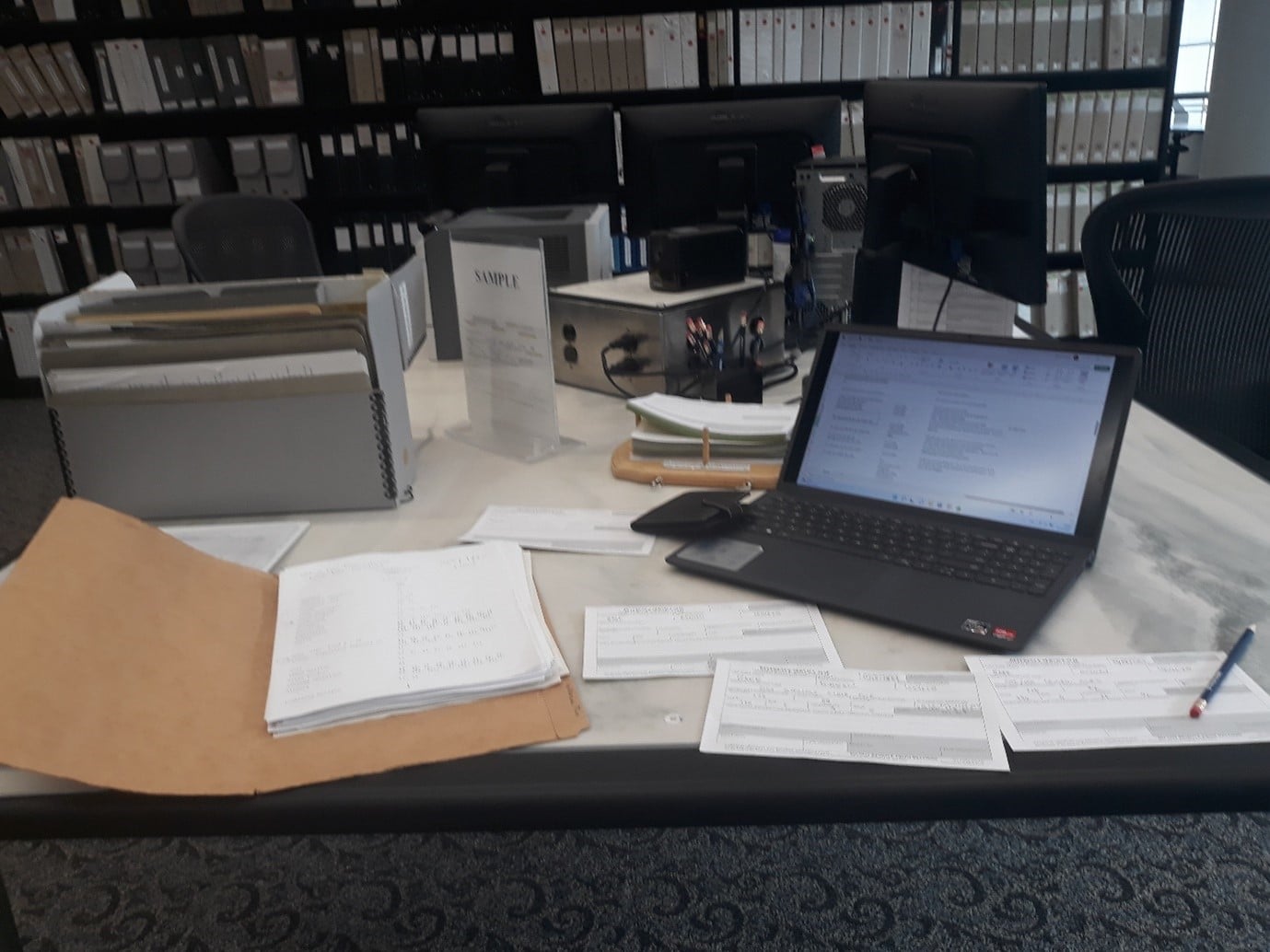

The author’s makeshift workstation on the third floor of NARA II. The bookcases in the background include finding aids for military holdings, of which OSS and CIA records are included. Two full bookcases are dedicated to RG 226 finding aids. On the table in front, three pull slips are visible. Source: Author’s photograph.

The system works, but does take time to understand and, especially if an entry has been re-boxed, can prove frustrating. There are few things worse than carefully filling out record pull slips, submitting them, receiving a cart of boxes, and realizing that they’re not what you wanted.

Not only should the available digital and paper finding aids, and sample pull slips but consulted to avoid this, but also the infinitely wiser ‘human’ finding aids: An exploratory email sent a few weeks before arrival to the archivist staff can shore up any expedition to College Park and when on site, it’s highly recommended to seek their advice, especially if you encounter any difficulty in finding documents.

At the same time, it is important to stay grounded: Archivists are not on staff to pinpoint specific documents or do research for visiting scientists. They are professional, highly competent, well-educated, and help researchers from all over the world as a matter of course. Many are multi-lingual and enjoy the ‘challenge’ of ensuring (polite) researchers find whatever it is that they are searching for or, at the very least, comb through the relevant areas during their research stay. On multiple occasions, I have experienced them go out of their way to accommodate researchers, and even entertain requests that seemed impossible to solve. In my own efforts, they have helped immensely.

Digitize

On one of my first trips to NARA in 2012, I purchased a flatbed scanner from a local office supply store and brought it in a piece of wheeled carry-on luggage to and from the facility on a WMATA bus for several weeks (thankfully, most areas in and around DC have sidewalks!). While there, I noticed researchers using a ‘gooseneck’ tablet holder and photographing documents with iPads – a trend that I gladly copied for my subsequent visit, ditching the bulky scanner. I also experimented with a camera, especially to capture microfiche, however, I found them unwieldy without a tripod (which again needed to be transported in a piece of luggage).

As of 2023, all of that is history, if you want it to be: NARA II now lends Fujitsu ScanSnap SV600 portable scanners to researchers on a first come-first served basis on the 2nd floor’s main reading room. I have never seen them ‘run out’, but it is advisable to secure one in the morning to be on the safe side.

Thanks to the wonders of technology and the progressive mindset that prevails at NARA II, all a researcher now needs to bring with them to create high-resolution digital scans of documents is a laptop with a USB port. Install the ScanSnap software, and you can scan and view documents in real time at your table/workstation from 9 AM to 5 PM. For non-local researchers, digitizing on site allows you to review and assess documents later at your convenience.

The author’s workstation on the 2nd floor reading room of NARA II. The portable scanner loaned out by the facility is visible to the right of the author’s laptop, while a box of archival documents is to the left of it. On the far right, a large cart, likely containing 20 or more boxes, is visible. Researchers at NARA II can freely select where they sit, however, only two researchers can sit at a single table. Source: Author’s photograph.

Pull Strategically

To make the most efficient use of your time at NARA II, I would like to conclude by sharing my experiences with “pulling” records.

For those who have never visited the facility, once you’ve identified the records that you’re interested in, you need to submit a paper request to “pull” them from the stack area where they are stored, known as a “pull slip”. [12] Once completed (on the third floor) and signed off on by an archivist, you’ll bring your pull slips down to the second floor and give them to an archives technician. They or their colleagues will then “pull” the boxes or files requested and bring them to the 2nd floor. When your surname appears on the screens on the 2nd or 3rd floor, go to the desk on the 2nd floor where you submitted your pull slips, scan your researcher ID, and fill out the back of the slip which the archives technician hands you. Then, a cart with your records will be brought out and you can review them at your workstation (one box at a time, one folder at a time).

While it sounds daunting here, the entire process quickly becomes second nature and is thoroughly explained in the new researcher tutorial as well as by archivists on the third floor. Technicians are only ever a glance away and can help you with any issues you might encounter with the documents (such as removing staples or other bindings), their container, or your pulls. Keep in mind that their job is to ensure that archival materials are kept safe and returned to the stacks in the same condition that they were retrieved from them so that future researchers can use them.

I have made the most of my pulls by filling out as many slips as possible on the first morning of my research trip or at home after the first day. Researchers can take a stack of empty pull slips home with them to maximize their time on site – another mini tip.

Up to 24 boxes can fit on a cart, and researchers are allowed two carts at any one time. This means that, in theory, a researcher can have up to 48 boxes of documents (but only access 24 of them). Keep in mind that a cart can only have boxes from one stack area. For OSS/SSU records, there are three main stack areas (190, 230, and 250) and several other minor ones.

To illustrate the usefulness of this: If, on your first day at NARA II, you fill out 50 slips, with 25 boxes from stack area 190, 15 from stack area 250, and 5 from stack area 230, you can take a maximum of 39 boxes (24 from 190 and 15 from 250).

Alternatively, if you know that the documents from stack area 250 will take less time to process, you can pull those 5 boxes and 24 from 190 or 15 from 250. That way, you’ll get the 5 easier boxes completed, but have many (likely, more difficult) boxes to work through waiting for you as well as another “pull” to get more of your boxes. It is good to always have a cart ‘in reserve’, in case one of your pulls is a bust. That way, you won’t lose valuable archival time.

There are researchers who submit individual pull slips and view one box at a time (which is absolutely fine), however, I have only done this near the end of my archival trips, when I want to look at a specific document or need to rescan something.

Whereas in the past, pull times were staggered throughout the morning and early afternoon, as of 2023, NARA II pulls now happen on demand, whenever a pull slip is received. As the facility closes promptly at 5 PM, it is not recommended to submit a pull slip at 4 PM and expect to be able to work on it that same day, however, it will likely be waiting for you the following morning.

Conclusion

Working with archival records at NARA II in College Park, Maryland can be a wonderful and extremely enriching and rewarding experience. The facility, which was built in the 1980s, is sleek and offers researchers a comfortable, tranquil, and quiet working environment. It is readily accessible by public transport (WMATA C8 bus) and there is a free shuttle bus that departs from Archives I (Archives-Navy Memorial, downtown DC) and returns there every hour, Monday-Friday, from 8 AM to 5 PM. Even though it is adjacent to a golf course and small forest, there is a cafeteria on site, as well as a large indoor/outdoor eating area. Many researchers arrive early in the morning, grab a quick bite to eat downstairs in the afternoon, and stay right up to 4:55 PM, when all archival records need to be returned. All members of staff, from the security guards to the cafeteria personnel to the archives techs to the archivists are professional, helpful, kind, and knowledgeable.

I hope that my insights prove valuable to you in your search for archival documentation on US intelligence, or even, your first visit to NARA II. Any inaccuracies or mistakes are entirely my own, however, the content of this post was written to the best of my knowledge.

Postscript

The primary purpose of my Botstiber grant was to finance several weeks of research at NARA II in support of articles and papers on US intelligence in postwar/early Cold War Austria. Just as visiting NARA II was a rewarding experience and one that I would encourage anyone to make, so too was applying for a BIAAS grant during the 2022/2023 period. The process was straightforward and well-documented. If you are considering conducting research on a topic with an Austrian-American dimension, there is absolutely no reason not to apply for a BIAAS research grant. With that, I would like to again thank BIAAS for supporting my research into US intelligence in Austria!

[1] See, for example (in alphabetic order), the works of Alfred Ableitinger, David Alvarez and Eduard Mark, Siegfried Beer, Günter Bischof, Ralph W. Brown III, James Jay Carafano, Peter Pirker, Kevin C. Ruffner, Erwin Schmidl, Eduard Staudinger, Florian Traussnig, and others.

[2] Although Smiley does rely on some archival information in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, it plays a far more significant role in the (nearly ignored) second novel in the so-called ‘Karla Trilogy’, The Honourable Schoolboy, set in Southeast/East Asia.

[3] See: Duncan Bare, Siegfried Beer; Being a “Solomon” in Washington: Evaluating and Processing OSS and SSU Intelligence from Austria, 1945–1946. Journal of Austrian-American History 18 October 2023; 7 (2): 169–212. doi: https://doi.org/10.5325/jaustamerhist.7.2.0169.

[4] For a comprehensive introduction to researching OSS records, see: Lawrence H. MacDonald, “The OSS and the Development of the Research and Analysis Branch,” in The Secrets War: The Office of Strategic Services in World War Two, ed. George Chalou (Washington: NARA, 1992), 78-102

[5] The Secret Intelligence (SI) and Counter-Intelligence (X-2) sections which comprised SSU were reorganized into Foreign Reports Branch (FRB) and Security Control Branch (SCB). These, in turn, were overseen by the Foreign Security Reports Office (FSRO). In the middle of June 1946, FSRO was integrated into CIG’s Office of Special Operations (OSO), but remained, de facto, part of SSU until the middle of October 1946. See: SSUAA to AMUAA, VIUAA, BRUAA: #1147, June 17, 1946, in: National Archives and Records Administration, Building II (hereafter, NARA II), Record Group 226, Entry 216, Box 1, Withdrawal Number 24878-24899.

[6] The May 1946 Progress Report from SSU Austria can be found in: FSRO-21, LS-010-531, William S. Mackenzie for the Chief of Mission to the Director, SSU, Washington, Monthly Progress Report for period of May 1–31, 1946, June 1, 1946, Entry 210, Box 310, WN 10831. There is a sort of June progress report, however, it differs significantly than those which preceded it and is more a status update from the mission’s chief, Al Ulmer. See: 1098 to Mr. Richard Helms, Chief Foreign Reports Branch M, SSU War Department; LS-010-705; Miscellaneous SI Affairs, Austria-Balkans, July 5, 1946 in: NARA II, RG 226, E 108B, B 76, F 625. Counter-intelligence (SCI/A, SCB) monthly progress reports are available up to September 1946, however.

[7] By April 11, 1947, Col. Quinn, SSU’s Director, reported that its remaining civilian personnel had been “terminated” and all military personnel had been “transferred or reassigned”. See Arthur B. Darling, The Central Intelligence Agency: An Instrument of Government to 1950 (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 1990): 99 and 119. For the May/June 1947 dates, see: See Lt. Gen. William W. Quinn, Buffalo Bill Remembers (Fowlerville, MI; Wilderness Adventure Books, 1991): 263.

This was the date that all SSU personnel were “fired”, with those deemed desirable for continued service rehired to CIG/OSO the following day, October 20, 1946.

[8] Underlined in original. See: Walter Pforzheimer to Assistant Deputy Director for Intelligence, January 28, 1970, General CIA Records, Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Digital Reading Room, available at: https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP72-00310R000200290016-8.pdf.

[9] They were also exempted from declassification on the grounds that they revealed “sources and methods” and were therefore vital to national security.

[10] See: Interagency Working Group (IWG), Nazi War Crimes & Japanese Imperial Government Records Final Report to the Untied States Congress, April 2007. (College Park, MD: Office of Records Services (NW), 2007).

[11] This is not a hard and fast rule, the author has found documents from 1947 and 1948, however, these appear to have been missed by classifiers rather than systematically declassified.

[12] For an excellent history of the pull slips themselves, see: Alan Walker, “50 Years of the Pull Slip”, April 2016, The Text Message. Available at: https://text-message.blogs.archives.gov/2016/04/26/50-years-of-the-pull-slip/. Last accessed: December 15, 2023.