“Lessons for Republicans”: John Adams’s Son-in-law Visits Vienna

By Jonathan Singerton

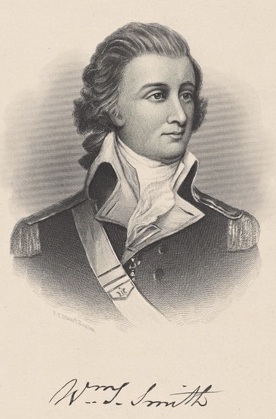

When Colonel William Stephens Smith (1755-1816) rode along the “most remarkably bad road” between Pirna and Litoměřice along the Elbe River, he joined an exclusive cadre of Americans who reached the Habsburg lands in Central Europe. In all likelihood, Smith became the fifth American to visit the Habsburg capital, Vienna.

In August 1785, Smith and his travelling companion, the future Venezuelan revolutionary Francisco de Miranda, set out for a tour of Europe. They hoped to see their great military hero, the ailing Prussian King Frederick II, during the annual military review at Potsdam. Both men shared an intense interest for the history of the Seven Years’ War and the chance to see the actual battlefields proved irresistible. The Habsburg Monarchy, therefore, became a spontaneous extension to the itinerary and offered them the hope of seeing Frederick’s great rival, Joseph II.

Smith pitched this “small tour on the continent” to his employer and future father-in-law, John Adams, for whom he worked as a personal secretary during Adams’s time as ambassador to Great Britain. Adams consented; Smith’s journey would be useful if he could gather information on commercial prospects for American goods in those places.[1] Just as the Habsburgs had Baron de Beelen-Bertholff and Joseph Donath in the United States, the Americans would have Smith and Miranda in Central Europe.

Abigail Adams also supported Smith’s plans wholeheartedly. At the time, Smith was vying for the affections of her daughter, who already had a suitor back in the United States; Smith’s journey abroad would give her daughter some much needed space to decide. But Adams requested him to “not travel too rapidly as to omit your journal, for I promise myself much entertainment from it upon your return.”[2]

Smith’s travel diary is a remarkably frank and descriptive journal, detailing every element of their trip. Despite the fact Smith knew his would-be mother-in-law wanted to read it, he catalogued his encounters with various prostitutes along the way—although Miranda’s exploits were recorded in greater detail.[3] Smith’s diary forms one of the most insightful and forthright commentaries on the Josephinist regime by a foreigner.

Smith’s first impressions of the Habsburg Monarchy came from the carriage window as they crossed the Saxon-Habsburg border on that road to Litoměřice on October 7, 1785. The abundance Catholic imagery dotting the roadside struck him the most: “at every crossroad is an image or crucifix, where the foot-passengers kneel to or kiss and horsemen raise the hat and cross themselves.”[4] His astonishment increased as they arrived in Prague where, he noted, the “priests, monks, and friars rule the roost.”[5]

Seeking some refuge from reminders of religion, they visited the Imperial Library in Prague. They marvelled at the collection of over 100,000 books on their tour with the imperial librarian, Johann Nepomuk Bartholotti. Smith noted how Bartholotti “spoke in raptures of our revolution” and “gave us his blessings and prayers for our success and the particular success of our country and our principles.”[6] Throughout the Habsburg Monarchy Smith was delighted to meet supporters of the American Revolution, whose support contrasted the negativity he and Miranda had experienced from Prussians, who spoke “with pleasing expectation of the Americans returning under the British yoke.”[7]

Smith’s biggest delight came during his visit to Vienna, where the pair arrived on October 14, 1785. They stayed at the rather grand Hotel Zum Weißen Ochsen—today Fleischmarkt No. 28.[8] They visited the Augarten, which Smith noted was freely accessible to the public. They also saw the public galleries of the Imperial Library “with fire, pen, ink, paper, and a free use of books for all,” calling it “in every respect the most superb of any we have seen.”[9] Compared to the overt Catholicism they had encountered in Bohemia, both Smith and Miranda marvelled at the enlightened activity of the Habsburg capital.

Smith saw this enlightened atmosphere as the result of one man: the emperor Joseph II. Already in Bohemia, Smith learned of his ecclesiastical reforms from the local newspapers and was impressed. Now in Vienna, he and Miranda hoped to see the revolutionary emperor up close. Their wish came true on the night of October 17, when they visited the city’s opera house. Smith immediately noticed the emperor sitting up front in his simple green and red military uniform.[10] This was the first time an American had seen a Habsburg ruler in the flesh and it left a deep impression on Smith. In his diary entry that night, Smith recorded a list of Joseph’s acts of humility: “He visits hospitals”; “He goes to his minister [… to] save him the trouble”; “he rides without a servant.”[11]

A few nights later, on October 20, Smith gazed upon the emperor again at the opera house and found it odd how he was the only one mesmerised. “You very rarely see any person, not even the military, looking. This is very singular.”[12] Smith spent the duration of the entire opera wondering how such a towering dynastic figure could be so normal and humble. “In a republic,” he noted, “Washington is reverenced and adored by all[; …] in a tyrannical government, as Prussia, Le Roi, is their terrestrial God and his subjects will freely sacrifice their lives to his caprice and humour.”[13] The fact that Joseph “laid aside the pomp and parade” yet still commanded such respect from his subjects greatly impressed Smith and rattled his developing political views. A military man, Smith previously felt that display, rank, and pageantry were essential to a ruler’s persona, but he now began to question whether this was entirely correct. Joseph II, who ruled a “mild government thought not republican but not tyrannical either,” could have important “lessons for republicans” back home.[14]

Smith’s journey ended a week later, but he carried his impressions with him. Stopping in Paris to see Thomas Jefferson, he regaled him with all that he had seen and learned in Vienna.[15] The revolutionary emperor might not have noticed Smith, but the American revolutionary had certainly noticed the emperor. It was a unique and poignant encounter in the early history of Austrian-American relations.

Jonathan Singerton is a specialist on the early connections between the Habsburg Monarchy and North America. He recently completed his PhD entitled “Empires on the Edge – The Habsburg Monarchy and the American Revolution 1763-1789” at the University of Edinburgh. He is currently a Plaschka Fellow at the Institute for Modern and Contemporary History at the Austria Academy of Sciences, Vienna.

Notes:

[1] John Adams to William Stephens Smith, 5th August 1785 in Gregg L. Lint et al, eds., The Adams Papers – Papers of John Adams, Vol. 17 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 301-302.

[2] Abigail Adams to William Stephens Smith, dated 13th August 1785 in Richard Alan Ryerson, ed., The Adams Papers – Adams Family Correspondence, Vol. 6 (Harvard University Press, 1993), pp. 266-267.

[3] Diary entries dated 6th and 9th October 1785. This and all diary entries below are contained in Archivo del General Miranda, Viajes, Diarios 1750-1785 (Caracas, 1929), 1: 352-436.

[4] Diary entry dated 7th October 1785, 415.

[5] Diary entry dated 9th October 1785, 415-416.

[6] Diary entry dated 10th October 1785, 419.

[7] Diary entry dated 19th September, 396-397.

[8] The original building no longer stands: https://www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Zum_wei%C3%9Fen_Ochsen

[9] Diary entry dated 15th October 1785, 423.

[10] Diary entry dated 17th October, 425.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Diary entry dated 20th October, 428.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid., see also entry for 27th August 1785, 372.

[15] Thomas Jefferson to Abigail Adams, 20th November 1785, in Richard Alan Ryerson et al, eds., The Adams Papers: Adams Family Correspondence, Vol. 6 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993), 462-464.

Further Reading:

Alexander von Hase, “Eine amerikanische Kritik am spätfriderizianischen System: zum Tagebuch von Col. William Stephens Smith, Adjutant von George Washington (1785),” Archiv für Kulturgeschichte, Vol. 56, No. 2 (1974), 372-393.

Grete Klingenstein, “Lessons for Republicans: An American Critique of Enlightened Absolutism in Central Europe, 1785,” in Solomon Wank et al, eds., The Mirror of History (Oxford, 1988), 181-212.

Richard H. Popkin, “Moses Mendelssohn and Francisco de Miranda,” Jewish Social Studies, Vol. 40, No. 1 (Winter, 1978), 41-48.

Paul C. Nagel, Descent from Glory: Four Generations of the John Adams Family (Harvard University Press, 1999).

Andrew Wheatcroft, The Habsburgs: Embodying Empire (Penguin, 1996).

Michael Zeuske, Francisco de Miranda und die Entdeckung Europas: Eine Biographie (Hamburg/Münster, Lit Verlag, 1995).

Archival Sources:

Archivo del General Miranda, Viajes, Diarios 1750-1785 (Caracas, 1929), 1: 352-436.

Learn More:

Biography of William Stephens Smith: https://www.masshist.org/adams/biographies#WSS

Smith’s letter to Adams requesting time off for his journey: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-17-02-0166

On Abigail ‘Nabby’ Adams: http://librarycompany.org/women/republicancourt/smith_abigail.htm

On her and her relationship other than Smith: http://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/royall-tyler-man-nabby-adams-wanted-marry/