Hölzlhuber’s America: An Austrian Artist’s Depiction of Antebellum Travel in Wisconsin and Beyond, 1856-1860

By Janine Yorimoto Boldt and Kristina E. Poznan

When Franz Hölzlhuber arrived in the United States from Austria in 1856, the United States was in deep debate over the future of slavery in its western territories and actively engaged in Native removal. During Hölzlhuber’s four years in America, war was raging in “Bleeding” Kansas, John Brown led a raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, and the Pony Express connected Missouri and Sacramento, California. Hölzlhuber’s path crisscrossed with many of these developments, which he recorded in sketches at the time, subsequently painted, and commented on over two decades later when exhibiting his American art back in Austria. “I endured many hardships and privations on wanderings in order to bring this or that sketch to paper,” he remembered.[1] Countless artists captured scenes of westward expansion, but Hölzlhuber’s depictions demonstrate an outsider’s assessment of antebellum America, particularly its race relations, beginning with his time at sea.

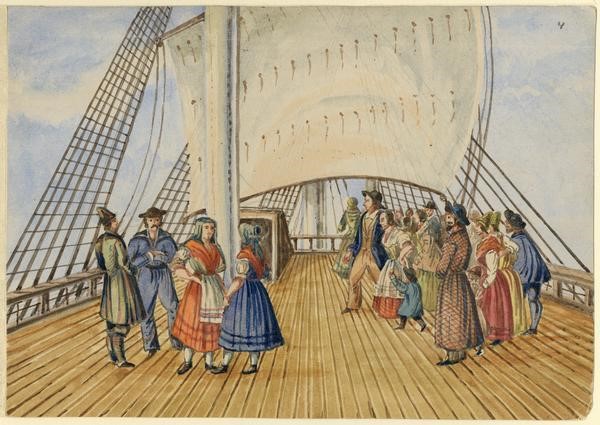

Hölzlhuber’s sketches from aboard the Tuisco are among the few visual depictions of a transatlantic journey in this time period. Most of those traveling with him were German immigrants. “A[n] immigration boat is like a swimming town on the Ocean,” he observed, “where one can find more entertainment than in some big cities.”[2] In the image “A Sunday on the High Seas during my Crossing to America,” the artist includes a number of people on the deck enjoying the clear skies. Hölzlhuber chose to focus the entire scene on the deck of the ship, carefully delineating the individual planks, which recede upward into the background. The tilted perspective draws the viewer’s eyes to the center of the image and the large white mast and then back down to the colorful figures, who wear the brightly colored clothing of the German working class. The attention of the larger group on the left appears to be captured by something outside the image. Perhaps they are watching whales, one of the activities the passengers could engage in during the long journey. The image is an optimistic scene that captures the excitement and camaraderie amongst the passengers, or at least, the excitement of Hölzlhuber. In his writings, Hölzlhuber recounted hours on the deck spent talking, or playing “Domino, cards or Lotto.”[3] It is a positive view of immigration to America that ignores the potential hardships faced during the long journey or obstacles that may still await the migrants in their new country.

Franz Hölzlhuber, “A Sunday on the High Seas during my Crossing to America,” ca. 1856. Watercolor, 8 x 5 ½ in. Wisconsin Historical Society. (https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM28043)

Hölzlhuber landed in New York City on June 14, 1865 and soon made his way to Milwaukee. The upper Midwest had a large community of German and Austrian immigrants engaged primarily in farming. Hölzlhuber himself had no such landed aspirations, coming, instead, to work and travel. In Milwaukee he conducted the choir for a Catholic church, played the organ in a synagogue, and taught drawing and music at the German-American Academy.[4] He traveled extensively in Wisconsin and later made his way down the Mississippi River to New Orleans. In all he visited Arkansas, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New York, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, Washington DC, and parts of Canada, making him far more traveled within the United States than the vast majority of Americans at the time. He documented his travels in sketchbooks and later watercolors capturing city scenes, landscapes, life along the Mississippi River, logging and railroad operations, and the various peoples he encountered, selling some of them to Weber’s Journal in Leipzig, Neue Illustrierte Zeitung in Vienna, Harper’s and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper in New York, and other papers.[5]

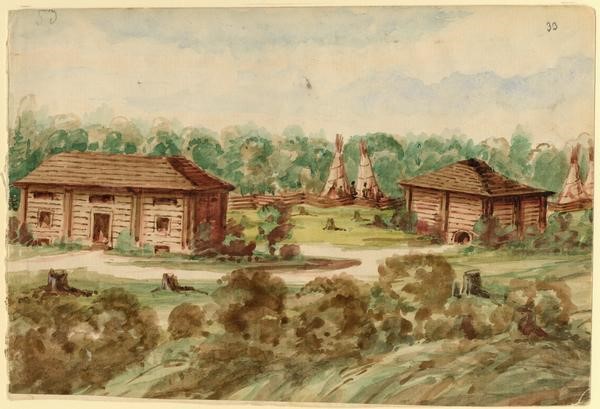

Among the most interesting images Hölzlhuber painted were those depicting Native peoples and the fur trade. He painted the interior of a fur-trading post near Yellow Lake, Wisconsin, giving us a rare document of what such buildings looked like. The walls are lined with furs as well as colorful textiles and jars of other dried goods. The images show Euro-American traders socializing with people of the Ojibwe nation (these images are now in the Glenbow Museum in Canada). Members of the Menominee, Omaha, Pawnee, Ponca, Sioux, and Winnebago nations also appeared in his works.[6] Although most images of the West and Indigenous Americans at the time depicted Indigenous Americans as a primitive or vanishing people, often in an expansive landscape, Hölzlhuber captures a snapshot in time. He painted Indigenous people alongside white settlers, more accurately representing the multi-cultural interactions in the Midwest.

In “The Fur-Trader’s House on Yellow Lake, Wisconsin,” we see this multi-cultural interaction in the landscape. Hölzlhuber recalled spending the night at this site and enjoying dancing with the Ojibwe, who he referred to as Chippewa Indians. A log house and stable anchor the scene. In between the structures, in the center of the image, are tipis. Though they are separated from the buildings with a fence, they are prominently placed in the composition. The small human figures are clustered near the tipis. All of the structures appear in harmony, as they are painted in similar colors, and peacefully blend into the landscape. In his writings, Hölzlhuber recounts that he purchased “some lovely silk ribbon” and “a pound of grease” for the “little Indian girl” he had danced with as a parting gift, emphasizing the peaceful encounter.[7] However, the tree stumps in the foreground hint at the ecological impact of western settlement even as the bright green trees in the distance suggest a landscape filled with endless resources.

Franz Hölzlhuber, “The Fur-Trader’s House on Yellow Lake, Wisconsin,” ca.1858. Watercolor, 8 x 5 ½ in. Wisconsin Historical Society. (https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM28155)

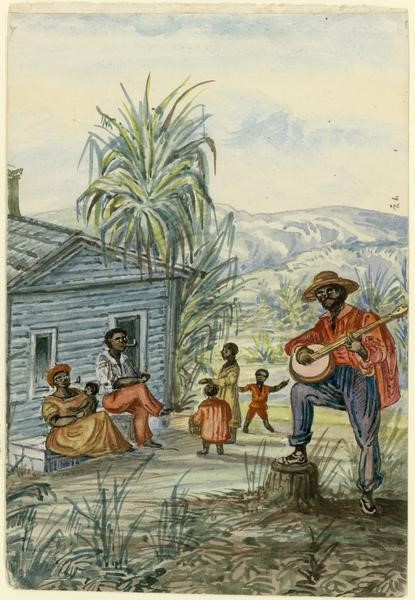

Black people also appear in a number of Hölzlhuber’s images. When Hölzlhuber traveled south, he was one of only a handful of artists who depicted enslaved people actually laboring in fields. Yet his watercolors appear neither critical of slavery nor in favor of it. Instead, he seems interested in capturing life as it was. By painting laboring enslaved people, Hölzlhuber acknowledged that American life was dependent on enslavement. But the images do not emphasize the brutality of slavery or the hard labor involved in cultivated crops like cotton and sugar. In one image, he painted an enslaved family singing songs and relaxing on a Sunday. This could be interpreted as him simply wanting to capture Black family life — he claims to have sketched them “as I saw them in South Carolina” — or as him downplaying the evils of slavery. Despite the lack of forthright expressions of Hölzlhuber’s views, his mentions of an illegal slave ship getting captured, John Brown’s raid, and a former student of his who died in the Civil War as an officer for the Union suggest where his sympathies might have lay. Other passages indicate that he did not ascribe to racist paradigms of the time, recognizing Blacks as artists with skills comparable to his own. “I had never seen two comicer as good as black James and red Joe,” an Irish man, he wrote. “Both had very good voices” — seemingly sincere praise from the choral director.[8]

Franz Hölzlhuber, “On a Sugar Plantation in South Carolina,” ca. 1859. Watercolor, 5 ½ x 8 in. Wisconsin Historical Society. (https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM28206)

Unlike many of the migrants he encountered in the Milwaukee areas, who relocated to stay in the United States, Hölzlhuber’s sojourn was always intended to be temporary. “America is a country of sweat and hard work,” he concluded after his travels, “specially for the farmer.” He warned that migration was not a path of ease for Europeans: “I have met a lot of unsatisfied people who were unhappy alone because of the fact that they had not been welcomes with open arms and who had to depent on their own power, but which they did not use.”[9] Hölzlhuber returned to Austria in 1860, preparing several Austrian metallurgical exhibits for World’s Fairs and eventually heading the museum and library of the Austrian State Railway. He exhibited his artwork from his American travels, allowing fellow Austrians to “see” America through his eyes. He spoke at many of his “Journey to America” exhibitions, explaining “all peculiarities and customs of North American life,” and sometimes sang and recited original poems.[10] Throughout his life, Hölzlhuber also sketched and painted many places in Austria, especially in Steyr.[11] Today, his North American sketches are in the collections of the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, Alberta, the Huntinton Library in San Marino, California, and the Wisconsin Historical Society in Madison, Wisconsin, as well as in private collections.[12]

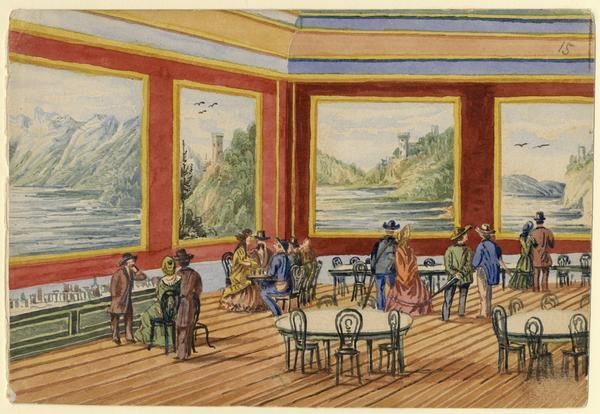

Franz Hölzlhuber, “Frankfurt Didaskalia,” 1858. Watercolor, 8 x 5 ½ in., Wisconsin Historical Society. (https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM28086)

Author Biographies

Janine Yorimoto Boldt, PhD, is the Associate Curator of American Art at the Chazen Museum of Art at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She was the 2018-2020 Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow at the American Philosophical Society, where she was the lead curator for the 2020 exhibition, “Dr. Franklin, Citizen Scientist,” and the co-curator of “Mapping a Nation: Shaping the Early American Republic.” Her current scholarship investigates the political function and development of portraiture in colonial Virginia and, in collaboration with the Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture, she recently launched the interactive database Colonial Virginia Portraits (colonialvirginiaportraits.org).

Kristina E. Poznan, PhD, is a scholar of American immigration and foreign relations history. Her work examines the relationship between transatlantic migration, migrant identities, and separatist nationalism in the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the context of migration to the United States. From 2017 to 2019 she was editor of Journal of Austrian-American History, sponsored by the Botstiber Institute for Austrian-American Studies. She is the managing editor of the Journal of Slavery and Data Preservation, the publication arm of Enslaved: Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade (Enslaved.org).

Further Reading

Boisits, Barbara. “Old Austria Meets the New World: The Painter, Writer and Musician, Franz Hölzlhuber (1826-1898).” In Ports of Call: Central European and North American Culture/s in Motion. Edited by Susan Ingram, Markus Reisenleitner, and Cornelia Szabó-Knotik: 3-32. New York: Peter Lang Publishing Inc., 2003.

“Franz Hölzlhuber.” steyrerpioniere, June 7, 2011. https://steyrerpioniere.wordpress.com/2011/06/07/franz-holzlhuber/.

“Franz Hölzlhuber’s Watercolors – Image Gallery Essay.” Wisconsin Historical Society. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS359.

Hölzlhuber, Franz. “Sketches from my travels.” Translated by Vera Kroner, 1959. Wisconsin Historical Society. http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/turningpoints/search.asp?id=1485.

Maser, Edward A., comp. “The American Sketchbooks of Franz Hölzlhuber: An Austrian Visits America in 1856-1860.” Lawrence, KS: University Kansas Museum of Art, 1959.

Nondorf, John. “An Eye Open for All that is Beautiful: The Wisconsin Sketches of Franz Hölzlhuber.” Wisconsin Magazine of History 98, no. 2, (Winter 2014-2015): 28-37.

“Sketches from Northwestern America and Canada: A portfolio of water colors by Franz Hölzlhuber,”American Heritage XVI, no. 4 (June, 1965): 49-64.

Notes

[1] Hölzlhuber, quoted in “The American Sketchbooks of Franz Hölzlhuber: An Austrian Visits America in 1856-1860,” comp. Edward A. Maser (Lawrence, KS: University Kansas Museum of Art, 1959), 1.

[2] Franz Hölzlhuber, “Sketches from my travels,” trans. Vera Kroner (1959), Wisconsin Historical Society, http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/turningpoints/search.asp?id=1485, 6.

[3] Hölzlhuber, “Sketches from my travels,” 6.

[4] Hölzlhuber, “Sketches from my travels,” 8-9, 12-15.

[5] Hölzlhuber, “Sketches from my travels,” 18-18a, 29. See “The Newhall House in the Main Street of Milwaukee,” the piece the Neue Illustrierte Zeitung published in 1883, at https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM28084.

[6] “The American Sketchbooks of Franz Hölzlhuber,” comp. Maser, 4-7.

[7] Hölzlhuber, “Sketches from my travels,” 24-25.

[8] Hölzlhuber, “Sketches from my travels,” 30.

[9] Hölzlhuber, “Sketches from my travels,” 20, 28-29.

[10] Barbara Boisits, “Old Austria Meets the New World: The Painter, Writer and Musician, Franz Hölzlhuber (1826-1898),” in Ports of Call: Central European and North American Culture/s in Motion,eds. Susan Ingram, Markus Reisenleitner, and Cornelia Szabó-Knotik (New York: Peter Lang Publishing Inc., 2003): 10-11; Hölzlhuber, “Sketches from my travels,” 1; “Hölzlhuber’s amerikanische Zimmerreise,” Der Alpen-Bote 93 (November 1874).

[11] A slideshow of some of Hölzlhuber’s Austrian art can be viewed at “Franz Hölzlhuber,” steyrerpioniere, June 7, 2011, https://steyrerpioniere.wordpress.com/2011/06/07/franz-holzlhuber/.

[12] “Franz Hölzlhuber’s Watercolors – Image Gallery Essay,” Wisconsin Historical Society, https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS359; “Franz Hölzlhuber drawings, 1856-1860,” mssHM 9892, Huntington Library, San Marino, California, https://catalog.huntington.org/record=b1819422.

Published on Tuesday, July 13, 2021.