Interwar Vienna’s ‘Female Secession’: From Vienna to New York and Los Angeles

By Megan Brandow-Faller

The Wiener Frauenkunst (Viennese Women’s Art) was founded in 1926 as an offshoot from the conservative Association of Austrian Women Artists (1910). The league drew its membership base from Women’s Academy graduates including ceramicists Wieselthier and Singer, who trained with Klimt Group members Adolf Böhm and Otto Friedrich as well as pioneering Austrian Impressionist Tina Blau-Lang. Led by Fanny Harlfinger-Zakucka, the Wiener Frauenkunst championed the Klimt Group’s philosophies on the equality of art and craft and the provocative idea of a separate feminine aesthetic and women’s ‘natural’ connection to the decorative— but in a way that subverted the gender-specific ideology slotting women into the applied arts in the first place. On one level, many Wiener Frauenkunst members flirted with ideas that they—precisely because of their longtime exclusion from academic institutions—possessed unique access to the sort of unmediated expressivity linked with the art of tribal peoples and folk cultures. Likewise, Wiener Frauenkunst artists tended to specialize in decorative and applied arts, fields of practice with long-term associations to the feminine, yet created innovative works embracing contemporary movements like Expressionism, cubism and primitivism. Yet, despite the way it provocatively embraced ideas of a feminine aesthetic and media, the ultimate goal of the group’s activism was to undermine gender discrimination in the art world altogether. Linking interwar Austria’s most radical women painters, architects, and a younger generation of artist-craftswomen, Harlfinger-Zakucka and her new league strove to define ‘women’s art’ on their own terms, unconstrained by the gendered dialectic surrounding ideas of women’s art.

Attracting interwar Vienna’s most progressive women artists, the Wiener Frauenkunst possessed a significant minority of Jewish members and strongly represented the intermedial artist-craftswomen dominating the Wiener Werkstätte (WW), co-founded in 1903 by Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser, during and after the Great War. Commencing production with metalwork, the WW (1903-1932) expanded to encompass leatherwork, toymaking, textiles, embroidery fashion and ceramics: many of which were fields that had (or came to have) particular associations to femininity. In the interwar WW, Women’s Academy graduates like Singer, Wieselthier, as well as Maria Likarz-Strauss (1893–1971) and Hilde Jesser-Schmid (1894–1985) experimented with the expressive possibilities of handcraft and ornament, laying claim to a version of decorative modernity that was later written out of mainstream modernist narratives.

Recruited for the WW because of their perceived naïveté and isolation from academic institutions, the female Secessionists pioneered a new genre of expressionist ceramics informed by the primitivizing currents of folk art and untutored children’s drawings. Secessionist educators were attracted to untrained female art students because their work was believed to embody the same untainted vitality and expressive immediacy as the art of primitive peoples or folk cultures (even as female art students were hardly as uninfluenced as their teachers believed and participated in a deliberate sort of ‘unlearning’ from the aesthetics of children’s drawings, tribal peoples and folk cultures).

These ‘feminine vessels’ exemplified bold experimentations in the expressive possibilities of handcraft beyond utility and function.

Of particular attention to critics were the functional vessels and sculptures created by Wieselthier, head of the WW Ceramics Department (1927-28), and protégées like Kitty Rix (1901–?),Singer, and Gudrun Baudisch (1907–1982), many of whom were of Jewish (Fig 1). Notably, much like Wieselthier, Singer was entirely untrained as a potter before her recruitment for the WW. Singer took inspiration from the figural subject matter of 18th C porcelain sculpture while inflecting her work with a sense of childlike naivete and nostalgia. Rix was similarly informed by movements like Cubism and abstraction while reinterpreting “primitive” archaic influences. Much of Rix’s ceramic work combined figuration with function, like her numerous prototypes for tableware, and was executed in a deliberately “naïve” style reflecting her study of folk art and untutored children’s drawings. Rix was captivated by the formal and decorative qualities of archaic Greek pottery and reinterpreted such preclassical sources through Modernist design principles.

Expressionist ceramics were notable for their formal asymmetries and imperfections, unevenly applied, bright glazes and decoration, and spontaneous processes of design, as visible in Wieselthier’s trademark Frauenköpfe. The Wieselthier Frauenkopf featured conspicuous distortions and faces painted to appear deliberately ‘made up’ and was informed by a long tradition of ceramic satire and humor. Critically, the heads confronted stereotypes limiting women’s art-making to her propensity to decorate and make up herself. Expressionist ceramics by Wieselthier, Singer, Rix and others figured prominently in Wiener Frauenkunst exhibitions.

Foreshadowing themes in the second-wave feminist collectives, Harlfinger-Zakucka wanted the Wiener Frauenkunst “not to function within the tired-out, conventional parameters of a league” but to organically unite “a small circle of women artists in all fields [of fine and applied art].”[1] Echoing the Klimt Group’s inclusive definitions of art and art-making, the collective sought to mend broken threads between professional artists and amateurs (long disparaged as dilettantes), encouraging matriarchal modes of transmission in the amateur practice of feminine craft media like embroidery. In the applied arts, Wiener Frauenkunst exhibitions constituted a forceful statement that handcraft media (like ceramics, textiles, embroidery, furniture and toymaking) could ‘think’ through contemporary movements like Expressionism, cubism, abstraction, and primitivism in a similar manner as painting or sculpture. Such convictions were shared by members like Emmy Zweybrück-Prochaska, well-known as a craftswoman, pedagogue and children’s book illustrator. Publishing widely on contemporary handcraft, she ran applied-arts workshops, called the Werkstätte Emmy Zweybrück-Prochaska, which specialized in textiles and embroidery and toys, in tandem with her progressive craft school for girls. Her school and workshops cultivated a seemingly “naïve” design language inspired by folk art and children’s drawings.

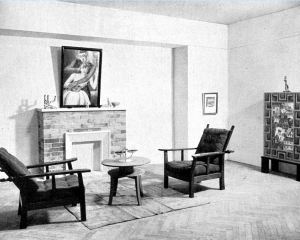

The Wiener Frauenkunst used perceptions of women’s suitability for the applied arts to pry open the masculine field of architecture. In a series of woman-centered architecture and design exhibitions curated by Liane Zimbler, Austria’s first state-certified woman architect, members exhibited model interiors integrating painting, sculpture and decorative objects into total aesthetic environments (Fig 2). These interiors contested the ways that modernist architectural theorists associated with the streamlined “machine aesthetic” or international style were pushing the decorative and handmade to the margins of modern art and design. Proponents of the international style advocated architecture and design that was largely un-decorated, reflecting modernist principles of functionality and rational construction. But Wiener Frauenkunst leaders buckled against such prescriptions, believing that the machine aesthetic was patently unsuited to domestic architecture, and led a concerted effort to reinsert decorative and handmade objects into modern interiors.

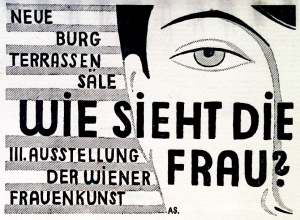

For her efforts in curating Vienna’s first women-only Raumkunst exhibition, “The Picture in the Interior,” Harlfinger-Zakucka received the 1929 Vienna City Prize. The Wiener Frauenkunst went on to stage a total of six major thematic exhibitions (1927–28, 1929, 1930, 1931, 1933, and 1936) that attracted the group widespread critical attention while provocatively confronting the gendered aesthetics attached to the group’s name (Fig. 3). Indeed, Wiener Frauenkunst members were acclaimed both domestically and internationally and were regularly featured in leading design periodicals like Deutsche Kusnt und Dekoration and Österreichische Kunst. Wiener Frauenkunst members rose to become the leading designers of the interwar Wiener Werkstätte, such as Maria Likarz-Strauss, the firm’s most prolific textile designer who headed its fashion department in its latter years, or ceramic artist Wieselthier (discussed in Part II), who headed the ceramics department and took on female pupils. Zimbler would regularly collaborate with an all-female design team on a lucrative series of interior design commissions (discussed in Part III), commissions which initially continued after the conservative direction of the early 1930s and the proclamation of the so-called “Austro-Fascist” state.

Yet the Female Secession’s boundary-defying handcraft, so closely linked with the “Jewish” taste of secessionist Vienna, hardly accorded with the Nazis’ selective appropriation of modernist design.

(To be continued in Part II)

.

Author Biography:

Megan Brandow-Faller is Associate Professor of History (with tenure) at the City University of New York, Kingsborough. Her research focuses on art and design in Secessionist and interwar Vienna, including children’s art and artistic toys of the Vienna Secession; expressionist ceramics of the Wiener Werkstätte; folk art and modernism; and women’s art education. She is the editor of Childhood by Design: Toys and the Material Culture of Childhood, 1700-present (Bloomsbury 2018) and the author of The Female Secession: Art and the Decorative at the Viennese Women’s Academy (Penn State University Press, 2020).

To learn more, please visit: https://www.meganbrandowfaller.com/

Notes

[1] Harlfinger-Zakucka, “Die ‘Wiener Frauenkunst’ und ihre Ziele.” Die Moderne Frau, 1, no. 1 (May 1926): 10.

Image Captions

Fig. 1: Vally Wieselthier, Gudrun Baudisch, and Kitty Rix, Wiener Werkstätte ceramics workshops, ca. 1925. Universität für angewandte Kunst, Sammlungen und Archiv (UAKS), Vienna, Austria. Inv. no. 10.529. Photo: Mario Wiberaz.

Fig 2: Anny Schröder-Ehrenfest, reception room from The Picture in the Interior exhibition, 1929. Chest on stand with decorative painting by Fritzi Löw-Lazar; design by Anny Schröder-Ehrenfest; ceramics by Susi Singer-Schinnerl (vase on fireplace and figure on chest on stand) and Lotte Calm (cat on fireplace); oil painting Pantomine by Anny Schröder-Ehrenfest; and enamel picture by Mitzi Otten-Friedmann. From WFK, Das Bild im Raum (Vienna: Werthner, Schuster, 1929), 32.

Fig. 3: Anny Schröder-Ehrenfest, cover image for How Does the Woman See? exhibition catalog, 1930. WFK, Wie sieht die Frau? (Vienna: Jahoda und Siegel, 1930).