VOICES

Code Name Mary: The Extraordinary Life of Muriel Gardiner

By Carol Seigel

In February 2020 I was fortunate enough to travel from England to the United States, funded by a generous grant from the Botstiber Institute for Austrian-American Studies, to research a forthcoming exhibit for the Freud Museum London on the extraordinary life of Muriel Gardiner.

As I visited the Library of Congress in Washington and met members of Muriel’s family across the US, little did I know how lucky I was to be making this trip–that the world was about to undergo a catastrophic pandemic (reminiscent of the Spanish flu that Sigmund Freud lived through 100 years ago), preventing global travel for many months.

Over a year later, the project has finally come to fruition. On a balmy September evening, the exhibition was launched by the actress Vanessa Redgrave and Muriel’s grandson Hal Harvey, and is on display until February 2022. It will then convert into a virtual exhibit hosted on the Freud Museum website.

Muriel’s Italian Driving License, after the War. Courtesy of © Freud Museum London.

But who was Muriel Gardiner, and what is the exhibition about? Muriel Gardiner had an extraordinary, multi-faceted life–a young American woman who courageously fought fascism in 1930s Austria; a member of Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic circle in 1930s Vienna, who became a psychoanalyst herself, practising and writing in the US in the post war decades, and closely connected to Freud’s most famous patient, the Wolf Man, about whom she wrote a seminal book; and the founder of the Freud Museum London with her friend Anna Freud, Sigmund’s daughter. Muriel is also believed to be the model for Lillian Hellman’s character ‘Julia’ in the 1977 Oscar winning film.

She is little known today but showed enormous courage and personal fortitude during her time in Vienna in the 1930s when her actions saved many lives. Muriel herself was proud to quote from a letter she received from Anna Freud in 1972: “I had not known of the intensity of your political activities in Vienna, only the vaguest rumours, and I was quite fascinated, even a bit envious. I like my own life very much, but if that had not been available and if I had to choose another one, I think it would have been yours.”

What is the story of this woman’s life, and how did an American woman become so immersed in the turbulent events of 1930s Europe? Muriel Morris was born in 1901 in Chicago into extreme wealth made from the meatpacking industry. She was interested in social justice at an early age. When she studied at Wellesley College, for the first time Muriel experienced the liberating effects of being away from her privileged family and all that they represented. She soon recognized how to use her wealth for good but never took her privilege for granted or adopted an ostentatious lifestyle.

Graduating from Wellesley in 1922, Muriel travelled to Europe, arriving in Italy on the eve of the Fascist March on Rome. She remained in Europe until the outbreak of the Second World War. Muriel’s time in Europe coincided with tumultuous political events, which she both witnessed and participated in. These strengthened her belief in an ideal of freedom and her personal imperative to fight against repression and authoritarianism, even when in great personal danger.

In 1926 she first visited Vienna, hoping to be accepted as a psychoanalytic patient of Sigmund Freud. She wrote: “Arriving in Vienna one May afternoon, when the streets and parks were filled with the scent of lilac, I immediately sat down and wrote a letter to Freud asking whether he would accept me as a patient.”. Freud referred her instead to his colleague, American-born Ruth Mack Brunswick. Mack took Muriel on as a patient and introduced this young American woman to the world of Viennese psychoanalysis.

Muriel became a permanent resident in Vienna and was enthusiastic about Red Vienna’s ground-breaking social reforms. Following a short-lived marriage to British musician Julian Gardiner (whose name she took) and the birth of her daughter Constance, she enrolled to study medicine at the University of Vienna to prepare her to become a psychoanalyst. There she was an acute observer of a rapidly deteriorating social and political Viennese landscape.

In February 1934 the Socialist movement was bloodily suppressed and a Fascist regime set up. Politically committed herself, and with close Austrian friends whose careers and lives were in jeopardy, Muriel joined the resistance to the fascist regime.

Portrait Photo of Muriel Gardiner, 1934. By Trude Fleischman. © Freud Museum London.

In the same year she met the English poet Stephen Spender, and the two became lovers. Spender was struck by Muriel’s beauty; she “recalled a portrait of Leda by Leonardo.” They had a great deal in common and both were “passionately concerned with the political situation in Germany and Austria.”

They were together as political violence erupted on the streets. The personal and political combined in Spender’s poem Vienna, expressing his intense anger at the suppression of the Viennese socialists, and equally intense emotions surrounding his lover. Their relationship did not last, though a strong friendship remained.

Muriel’s involvement in the resistance movement became intense. From 1934 through March 1938, when Nazi Germany annexed Austria, she was involved in countless illegal actions designed to keep the spark of resistance alive against a repressive regime. For almost four years, she regarded it as perfectly natural to take overnight ‘sightseeing trips’ by train to Prague in order to pick up false passports for her Viennese comrades.

A rich American, speaking both English and German, leading ostensibly a blameless life, was a huge asset to the resistance. Each action was fraught with danger, but Muriel calmly continued her medical studies, her analysis, and family life with her daughter Connie.

Muriel Gardiner’s Cottage. Courtesy of © Freud Museum London.

Under the code name ‘Mary’ her life in the resistance was one of clandestine meetings, obtaining false identity documents, hiding those wanted by the authorities, making illicit border crossings into Czechoslovakia, and smuggling papers, money, and passports. She concealed fugitives in her cottage in Sulz, deep in the Vienna Woods. One of these was Joseph (Joe) Buttinger, the leader of the Social Democrats in hiding. Joe and Muriel fell in love, and Muriel took on the responsibility of keeping Joe safe from the police.

In March 1938, following the Anschluss, the Nazis took direct control in Austria. Life became even more dangerous for any opponents of the regime. Muriel smuggled Joe and Connie out of the country to France but remained in Vienna–ostensibly to complete her medical studies. She engaged in further dangerous resistance work but also sought all legitimate means to assist Austrians, especially Jews, to escape: procuring passports, seeking jobs overseas, and securing affidavits from the American consul in Vienna.

Of the many risks Muriel undertook, one particularly strikes me. In support of her Jewish classmates, she registered her religion as Jewish (her father’s religion), although she knew Jews were not allowed to graduate. She did finally gain her medical degree, and left Vienna shortly after.

Re-joining Joe and Connie in Paris, she was able to send Connie back to the US. Joe spent some time in a French internment camp. War had already broken out before Muriel and Joe sailed on the last wartime ship to leave France for New York.

Muriel Gardiner and Joseph Buttinger at Juan les Pins, August 1939. Courtesy of © Freud Museum London.

Back In New York, Muriel immersed herself in relief efforts. She helped German and Austrian refugees build new lives in America (many stayed in her own apartment). For those still trapped in Europe, she obtained emergency US visas and sent money for ship passages, living expenses, and exit documents.

Joe and Muriel became involved with the International Rescue and Relief Committee, and both returned to Europe after the war to help the relief efforts. Muriel completed her medical training in the US during the war and spent the next decades practicing as a well-respected psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, educator, and writer.

One of her books was The Wolf Man and Sigmund Freud about Sigmund Freud’s most famous patient, Sergei Pankejeff (also known as The Wolf Man). Muriel had known Pankejeff in Vienna, taking Russian lessons with him, and helping him after the devastating suicide of his wife in 1938. They continued a warm and regular correspondence after the war which lasted until old age.

In the 1970s a controversy arose concerning whether Muriel was the anti-Nazi activist ‘Julia’ depicted by the author Lillian Hellman in her supposedly autobiographical memoir Pentimento. The story was subsequently filmed as Julia, starring Jane Fonda and Vanessa Redgrave. Gardiner dealt with the controversy with discretion, but most were convinced that Hellman had used the events of Muriel’s life without proper acknowledgment. The notoriety which followed publication of Pentimento encouraged Muriel to finally tell her own story in her memoir Code Name: Mary, published in 1983.

Towards the end of her life Muriel was also instrumental in the establishment of the Freud Museum London. She had become friendly with Anna Freud after the war and worked with her to enable a museum after Anna Freud’s death. Muriel financed the subsequent creation of the Freud Museum London through her family foundation.

Freud’s Study at the Freud Museum London. © Freud Museum London

Muriel was always modest about her bravery but pleased to have it acknowledged when, decades later, she received the Cross of Honor First Class from the Austrian government for her resistance activities. She died in 1985, aged 84. I believe her old friend Stephen Spender described her best: “Compassion was the source of Muriel’s political involvement, and she had the intelligence, courage and determination to act on it.” I hope that the exhibition at the Freud Museum does justice to this extraordinary woman and the difference that she made to so many in her lifetime.

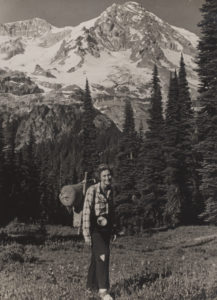

Muriel Gardiner in Arosa, Italy, date unknown. Courtesy of © Freud Museum London.

Author Biography

Carol Seigel is the Director of the Freud Museum London. A historian by training, she has been at the Freud Museum since 2009, and worked previously in a number of other London museums. She researched and curated the exhibition Code Name Mary: The Extraordinary Life of Muriel Gardiner.

Further Reading

Appignanesi, Lisa, and Forrester, John. Freud’s Women, Weidenfeld 1992

Berger, Joseph. “Muriel Gardiner, Who Helped Hundreds Escape Nazis, Dies,” in The New York Times Biographical Service. February 1985, p. 156.

Birkle, Carmen. “Heroines of Austria and yet American: Lillian Hellman, Muriel Gardiner, and the Promotion of Resistance.” Cultural Politics and Propaganda: Mediated Narratives and Images in Austrian American Relations. Ed. Waldemar Zacharasiewicz and Siegfried Beer. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences, forthcoming 2021.

Buttinger, Joseph. In the Twilight of Socialism: A History of the Revolutionary Socialists of Austria. NY: Frederick A. Praeger, 1953.

Gardiner, Muriel. Code Name “Mary”: Memoirs of an American Woman in the Austrian Underground. First printed 1983, Reprinted by Freud Museum London 2021

Gardiner, Muriel (ed). The Wolf-Man and Sigmund Freud. Psychoanalytic International Library, No. 88. London: Hogarth Press. 1972.

Hellman, Lillian. Pentimento. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1973.

Isenberg, Sheila. Muriel’s War: An American heiress in the Nazi resistance Palgrave Macmillan, 2010

Wright, William. Lillian Hellman: The Image, the Woman. NY: Simon and Schuster, 1986.

Young-Bruehl, Elisabeth. Anna Freud: A Biography. NY: Summit Books, 1990.

Archival Sources

Freud Museum London Archive https://www.freud.org.uk/collections/archives/

Muriel Gardiner Papers, Library of Congress, 1890-1986 https://www.loc.gov/item/mm87062007/

Links

Code Name “Mary,” Muriel Gardiner’s memoir, reprinted in 2021 by the Freud Museum London https://shop.freud.org.uk/collections/code-name-mary-the-extraordinary-life-of-muriel-gardiner/products/code-name-mary

Code Name Mary: The Extraordinary Life of Muriel Gardiner, Freud Museum London exhibition 18 September 2021 – 6 February 2022

https://www.freud.org.uk/exhibitions/code-name-mary-the-extraordinary-life-of-muriel-gardiner/

The Real Julia – a film made in 1987 by the NYU Center for Bioethics

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ct4tw02mQGI

Published on November 9, 2021.