VOICES

From the Post WWI Aid in Austria & Central Europe Symposium

By Friederike Kind-Kovács

1919-2019: The Legacy of Transatlantic and Transnational Aid to Central Europe

PD. Dr. Friederike Kind-Kovács, Senior Researcher, Hannah Arendt Institute for Totalitarianism Research at the TU Dresden

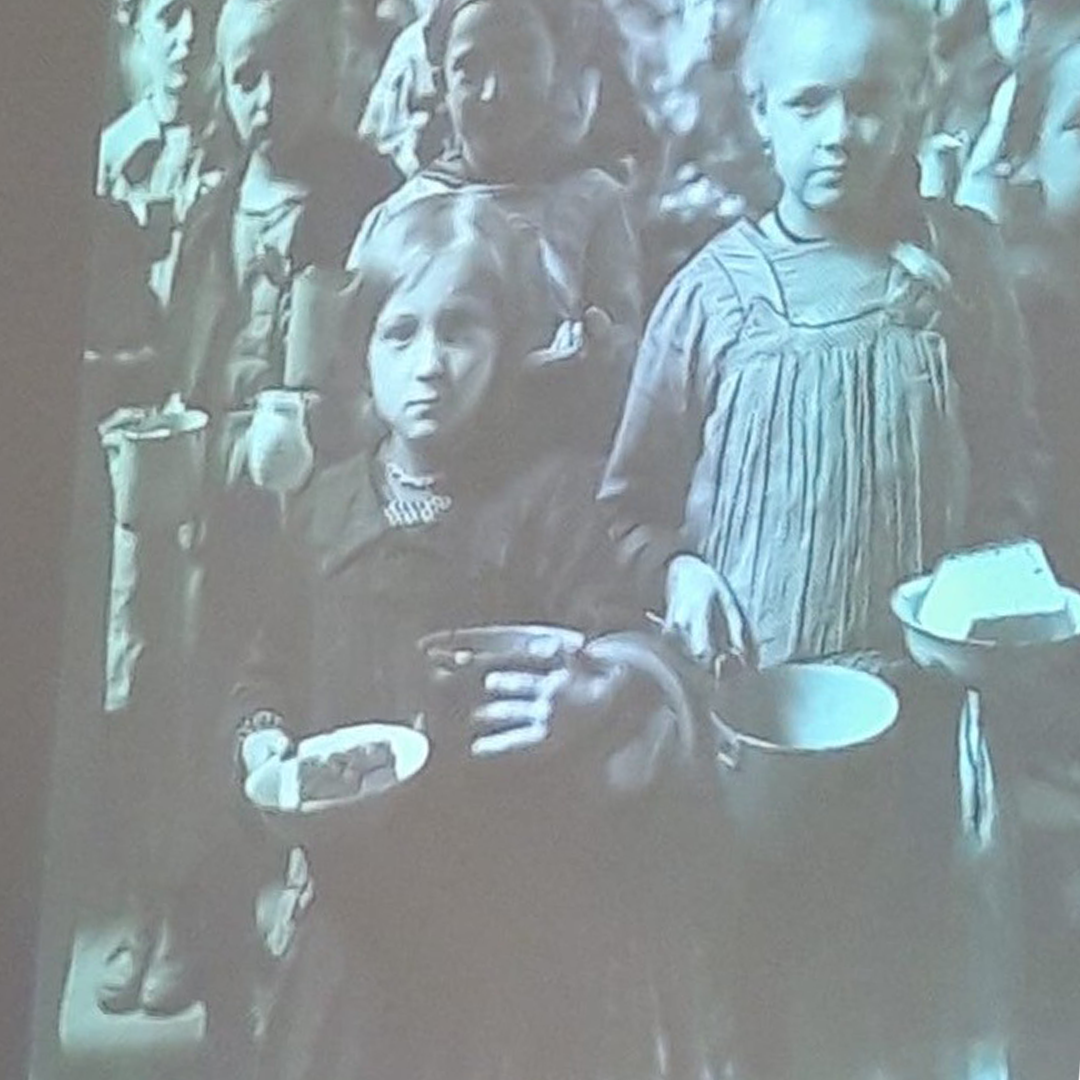

Throughout many years of historical research in the field of humanitarian child relief in Budapest after WWI, I have attended many conferences that dealt in one way or another with humanitarian aid. Yet not a single conference has ever exclusively dealt with humanitarian aid to Central Europe after the First World War; hence, I was more than honored and glad to be invited to speak at the recent conference on “Post World War I Aid in Austria & Central Europe,”[1] which took place between September 26 and 27, 2019, at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. The initial idea for the event did not come from an academic, but from Gregor Medinger, the former president of the American Austrian Foundation. Out of his personal interest in the experience of his mother and aunt (depicted in a painting shown during the conference) as participants in the so-called “children’s trains” or “child transports” from Vienna to Holland in the early 1920s, Medinger felt it was high time to bring some more attention to the postwar aid initiatives.

In cooperation with Dr. Franz Adlgasser from the Academy of Sciences, Medinger invited a diversity of European and American scholars to speak about their research on transnational and transatlantic humanitarian aid to Austria and Central Europe in the postwar period.[2] In his introductory remarks, Medinger prompted us with questions: Why are the children’s trains such an unknown story? Why do we not know about this part of Europe’s post-WWI history, even as scholars in Europe and beyond have spent the past years discussing every detail and dimension of the First World War itself? Accordingly, in this 100th anniversary of 1919, the year humanitarian relief on behalf of Austria and its neighboring states launched, this conference was designed to remind us of the large humanitarian endeavor in postwar Europe.

While the “Marshall Plan,” the post-WWII European Recovery Program, is – up to today – in people’s mind and consciousness all over Europe, and has – as a term – developed its own life, post-WWI relief activities are hardly part of today’s public discourse or memory, as Eva Nowotny from the Austrian Marshall Plan Foundation indicated. Yet, the survival of hundreds of thousands of children in the immediate postwar years was dependent on American and international relief and assistance. Institutions like the American Relief Administration (ARA), the Save the Children Fund (SCF) and its International Union (SCIU), the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), and the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), as well as courageous individuals like Herbert Hoover, Eglantyne Jebb, and many known and unknown volunteers, were invested in rescuing the lives of Central Europe’s starving children. Contrary to this large-scale humanitarian endeavor back in 1919, Nowotny observed, we today criminalize the immediate relief of migrants, let people drown in the Mediterranean, withdraw the support from NGOs that dare to help refugees, demonize and criminalize individuals that rescue people from the sea, and ridicule those that dare to help. Therefore, it is crucial to recall how the U.S. and other states reacted to children’s heightened needs that were caused by hunger, destitution, neglect, and resulting diseases in 1919. The American ambassador to Austria, Trevor D. Traina, stressed the value of the U.S.’s special transatlantic relief endeavors, the significance of which is still recognized a hundred years later. In particular, he appreciated the fact that the initiative for this conference came from engaged individuals and interested scholars rather than the American government, so that this conference could be free from any type of “self-congratulatory” hype.

Similarly, Siegfried Beer from the Botstiber Institute for Austrian-American Studies stressed the timing of the conference as occurring at a crucial time in Austria. While a hundred years ago Austria herself received massive aid on behalf of her starving children, Austria was nowadays rather unwilling to provide help and aid to displaced children, refugees and asylum seekers. Beer expressed his hope that this conference would make us again aware of this discrepancy between people’s past and present willingness to help. Likewise, George H. Nash (Massachusetts)[3] emphasized the conference’s significance in its millions of lost lives, the subsequent “greatest famine since the 30-year war.” Leon Botstein (Bard College) argued in his keynote lecture, “The Relevance of the Great Humanitarian Actions Post World War I Seen through a Contemporary Lens,” along a similar vein. Botstein challenged our – at times – one-sided perspective on the First World War, which tends to forget about the humanitarian dimension of its aftermath, and drew parallels between the past and the present in terms of people’s willingness to provide help to those that suffer. He employed Hannah Arendt’s idea of the war’s “banality,” not just in terms of its evil but also of the suffering it caused, its immense and irrational toll on soldiers, the senseless loss of lives, and of the enormous traumatic shock and memory this loss of lives caused. Similarly, wealthy societies today rarely question the “banality of suffering” confronting forced migrants, refugees and displaced people, while NGOs and any prominent individuals seem powerless to defy or oppose the enduring apathy.

When remembering the war’s aftermath in 2019, we should be equally aware of the other dimension of the Great War: the giant transatlantic relief mission as a response to the catastrophe of WWI. The conference should restore our memory to the great humanitarian endeavor initiated by Herbert Hoover, which aimed not only at the alleviation of individual suffering, but also at preserving European civilization itself. Hoover was taken by the fundamental notion of children’s innocence while driven by a paranoia that parents would exploit their children and take away their food, like in the “Hänsel & Gretel” tale, Botstein observed. Hoover was not solely invested in emergency relief; he also empowered destitute countries to help and sustain themselves. (Bertrand M. Patenaude, Stanford)

Yet, why did WWI cause such a humanitarian response back then, and why do we find ourselves today in such a moral limbo when it comes to responding humanely to near and distant suffering? How did we become insensitive to suffering? Why does our life just go on “without missing a heartbeat” when seeing distant others suffer, as Botstein put it? Are the stories and images of the 20th century’s countless human-made catastrophes – the Holocaust, Hiroshima, the Khmer Rouge, Rwanda, mass shootings in the U.S., and refugee crises – so ubiquitous that current humanitarian crises leave us with no feelings of outrage or empathy? Why don’t the Americans stand up against the near-concentration camp conditions in the U.S., which is itself an offence to the American moral authority, Botstein asked. Instead, current politics are driven by mythic nationalism, a deep-rooted mistrust in science, a lack of faith and convictions, widespread anti-immigrant sentiments, racism. Summoning the charge of the post-WWI enterprise in compassion, in giving and providing help, in transferring wealth to the needy, this conference should reawaken us from our moral exhaustion, de-sensitivity and inaction.

Apart from more than a dozen talks about transatlantic food relief to Vienna and the Austrian hinterlands, to Hungary’s children, to Jewish children, to Czech and Slovak minors, and about children’s trains to Sweden, Holland, and Belgium, the conference organizers wanted their audience and participants to physically share the children’s experience back in 1919. They used the lunch break to remind its audience – literally – of children’s destitution and dependence on relief food back in 1919. Conference attendants were offered the very same relief dishes which Austrian children received from the ARA after WWI. The lentil dish and the meat-noodle dish were prepared after historical recipes. Instead of cocoa, we, however, received a coffee. The idea to make donors physically re-experience children’s scarce rations of relief food was already used in Hoover’s “Invisible Guest Dinner” that was organized on December 29, 1920, in the grand ballroom of the Commodore Hotel in New York City to collect donations for Europe’s starving children from the capital city’s financial elite.[4] Yet, prior to this contemporary “Invisible Guest Dinner” in Vienna of 2019 most attendants had been quite aware of children’s destitution back then. Conference attendants had been either involved in historical research about humanitarian aid back in postwar Europe or were the descendants of those children who had benefitted from Hoover’s relief or the postwar children’s trains. Therefore, this conference succeeded in enabling a discourse among scholars, descendants and representatives of transatlantic institutions about past and future research endeavors.

Apart from a planned conference publication, the topic of humanitarian aid in Central Europe has and will produce a number of publications in the coming years. Thanks to a recent Botstiber Fellowship in Transatlantic Austrian and Central European Relationships at the Institute for Advanced Study in Budapest, I recently completed the book manuscript, Budapest’s Children: Humanitarian Relief in the Aftermath of the Great War, which investigates the ‘glocal’ dimension of humanitarian child relief. My book deals with various types of humanitarian child relief in post-WWI Budapest, and at this conference, I presented the chapter on children’s trains from Budapest to Holland and Belgium in the early 1920s, relying on interviews I conducted with a handful of former child evacuees. My book will be submitted to the new book series by Elizabeth Dunn and Georgina Ramsay, “Worlds in Crisis: Refugees, Asylum, and Forced Migration” at Indiana University Press, which seeks to investigate not only “the complexity of lived experiences of displacement” but also “[h]ow […] humanitarian agencies, aid industries, and government resettlement policies benefit or exclude refugees and migrants?” Apart from the topics of migration and humanitarian aid, the study of the postwar period also triggered the production of innovative scholarship on hunger in the aftermath of the war.[5] The International Research Network “Hunger Draws the Map: Blockade and Food Shortages in Europe, 1914-1922” by the Leverhulme Trust[6] has comparatively researched various dimensions of hunger. Such research and publishing projects demonstrate the great extent of original historical research still warranted for the post-WWI period. Against this backdrop, this Vienna conference might serve as an appeal and impetus to form an international and even transatlantic research group to comparatively study children’s humanitarian relief, both through transatlantic food aid, and the so-called children’s trains across post-WWI Europe. Such projects could enlighten us about past solutions to moral dilemmas and challenges involved in migration, displacement, and uprootedness, and offer ideas that advocate new collaborations and alliances in rescuing those in need.

The symposium was organized and funded by:

The American Austrian Foundation

Institute for Modern and Contemporary Historical Research

of the Austrian Academy of Sciences

The Austrian Marshall Plan Foundation

Supported by:

Austrian Academy of Sciences

With additional funding provided by:

Botstiber Institute for Austrian-American Studies

Gregor Medinger

About Friederike Kind-Kovacs

Dr. habil. Friederike Kind-Kovacs is a senior researcher at the Hannah Arendt Institute for Totalitarianism Studies at the TU Dresden. She was habilitated in 2019 in Southeast- and East European, as well as Modern/Contemporary, History at the University of Regensburg where she also served as an assistant professor. Recent fellowships include the Senior Botstiber Fellowship in Transatlantic Relationships at the Institute for Advanced Study in Budapest and a fellowship at the Imre Kertész Kolleg in Jena. She is the author of Written Here, Published There: How Underground Literature Crossed the Iron Curtain (CEU Press, 2014), a monograph for which she won the University of Southern California Book Prize in Cultural and Literary Studies in 2015. She also co-edited two volumes: From the Midwife’s Bag to the Patient’s File: Public Health in Eastern Europe (CEU Press 2017) and Samizdat, Tamizdat and Beyond. Transnational media during and after socialism (Berghahn Books 2013). Her current book project is entitled Budapest’s Children: Humanitarian Relief in the Aftermath of the Great War.

[1] “Fast Vergessen: Die Retter der Kinder Wiens,“ Wiener Zeitung 23.09.2019, https://www.oeaw.ac.at/fileadmin/NEWS/2019/Newsletter/09/PostWorldWarIAidinAustria_CentralEuropeProgram.pdf

[2] https://www.wienerzeitung.at/nachrichten/panorama/oesterreich/2030191-Fast-vergessen-Die-Retter-der-Kinder-Wiens.html?em_no_split=1

[3] George H. Nash, The Life of Herbert Hoover. W.W. Norton, 1983.

[4] See for this my article on “Compassion for the Distant Other. Children’s Hunger and Humanitarian Relief in the Aftermath of the Great War,” in: Beate Althamme, Lutz Raphael and Tarmara Stazic-Wendt, Rescuing the Vulnerable. Poverty, Welfare and Social Ties in Modern Europe. New York-Oxford: Berghahn 2016, 129-159.

[5] For instance, Mary Elisabeth Cox, Hunger in War and Peace: Women and Children in Germany, 1914-1924. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2019.

[6] The research network was run between 2016 and 2019 by Dr. Mary Elisabeth Cox, Dr. Claire Morelon, and Prof. Hew Strachan.