The Fiume Crisis: Made (But Not Primarily) in the USA

By Dominique Kirchner Reill

What would have happened if Woodrow Wilson and his corps of American experts had focused less of their post-WWI energy on the northeastern Adriatic port town of Fiume? Perhaps the Paris Peace Conference would not have collapsed in diplomatic deadlock, leading to the only Great Power walk-out of the entire proceedings. Perhaps Japan would have been denied the mandate over mainland China. Perhaps two successive Italian governments would not have fallen apart. A charismatic dictator-poet might not have founded a rogue republic in the city. Italian pirates might have idled on the Adriatic, instead of attacking ships and scoring booty to fund the poet’s Fiume regime. Peace might have reigned then, in Fiume, over the 1920 Christmas holiday with no need to chase out said poet and his followers. Perhaps Fiume would not have become the smallest successor state of post-WWI Europe. And perhaps all the nationalist extremism that percolated around this upheaval wouldn’t have convinced so many Italians that only Mussolini with his militaristic takeover would deliver Italy the expansionist, national grandeur so many believed it deserved. And, finally, perhaps today the city, today’s Rijeka in the Republic of Croatia, would not have witnessed heart-wrenching histories of nationalist erasure where Slavic speakers and Jews suffered exclusionary politics and violence at the hands of the Fascist and Nazi regimes, followed by tens of thousands of Italians fleeing after Fascism’s fall in order avoid a similar fate.

Musing about what might have been—or not—is fun for dinner parties, but it makes for sloppy, slippery history. What we do know: Many blamed the 1918-1921 Fiume Crisis, which led to all the extraordinary events that did happen, on American diplomatic pressure. My new book, The Fiume Crisis: Life in the Wake of the Habsburg Empire, explains why many believed the Fiume Crisis was “Made in the USA” and why that idea is wrong: Local conditions in Fiume spurred on the crisis; American interference just failed to resolve it.

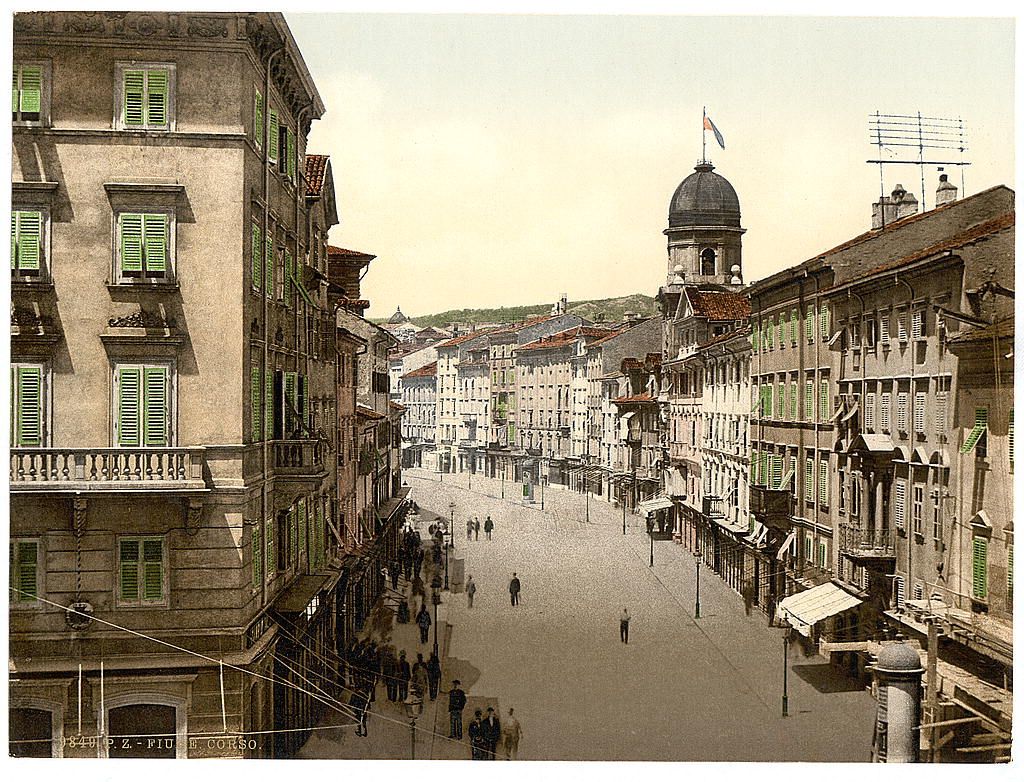

Map of Fiume before the end of World War I, when the semiautonomous city-state was part of Habsburg Hungary.

So, who considered the 1918-1921 Fiume Crisis American-made and why?

The answer to the first question is easy; the second is a bit more complicated.

While some historians agree the US helped cause the Fiume Crisis (to a point), most of the people who indicated American responsibility were Italians—largely, diplomats, publicists, and nationalist activists. The answer to why Italians believed Americans were to blame for the predicaments concerning Fiume lies in the tug-of-war of Great Power diplomacy and in a firm belief that Wilson betrayed promises he had made for a Fourteen-Points peace to end all wars.

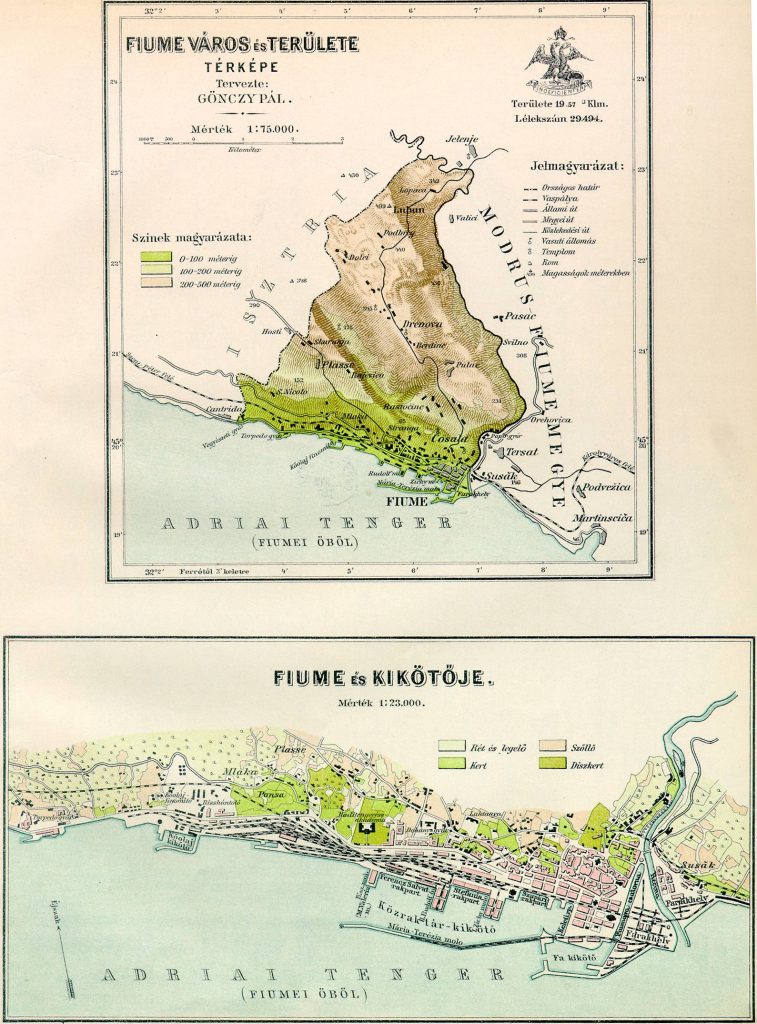

Picture of Italians preparing to celebrate Wilson’s arrival in Rome, when Italians thought the Fourteen Points would support much of their hopes for territorial expansion in the Adriatic.

In 1918, when Wilson published his Fourteen Points, he explicitly said that the “peoples of Austria-Hungary . . . should be accorded the freest opportunity of autonomous development,” and that “a re-adjustment of the frontiers of Italy” would be promoted “along clearly recognizable lines of nationality.” When Wilson’s Fourteen Points were announced, Fiume was a semiautonomous city within Habsburg Hungary whose population was made up of almost 50% Italian-mother-tongue speakers. The city’s autonomous municipal government had declared in late October 1918 that Fiume wanted to be annexed to Italy, explaining their reasoning with words like “national self-determination.” Italy had only entered WWI because of promises of territorial expansion along the Adriatic at Habsburg expense—though Fiume was not included in these deals. Along with the statesmen, a large chunk of Italian nationalist media circles and an increasingly vocal segment of Italian popular opinion assumed that Fiume’s future was obvious. It should and would go to Italy.

Going over the Fourteen Points, one can imagine why Italians thought it would be easy to absorb Fiume into their state. Autonomous development? Well, the local autonomous government had declared its desire to be annexed to Italy: check mark. Lines of nationality? The majority of Fiume’s population could be considered Italian: check mark again.

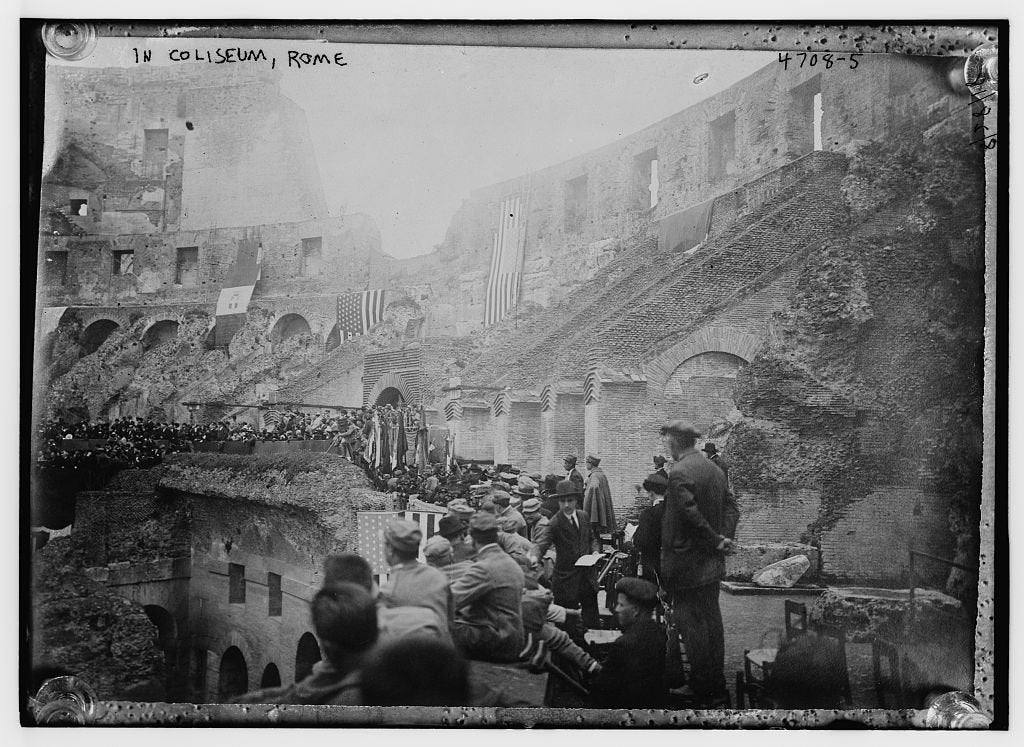

South Slav activist meeting in Sušak, a town outside Fiume, probably April 1919, with an American flag proudly displayed and a picture of Wilson in the middle, with the writing saying “Long Live Wilson!”

Whatever Italians read into the Fourteen Points before the Paris negotiations began, Wilson’s vision was the diametric opposite. Not only did he not think that Fiume should be joined to Italy, he made Fiume a showcase of his fight against Italian imperialism. So determined was he to block Italian annexation of Fiume that after months of diplomatic haggling, Wilson said explicitly that Italy would not get Fiume “so long as I am here.”[1]

And here we arrive at the core of why the Fiume Crisis can be considered an American-made fiasco: Though Wilson had said that peace would be made cooperatively, he had also collected a group of American experts—known as the “Inquiry”—to put together “guaranteed positions” on touchy diplomatic issues like Fiume. As Wilson told the Inquiry members while on their steamship voyage to Paris, “Tell me what’s right and I’ll fight for it.”[2] The six geographers, linguists, political scientists, and historians assigned to the Fiume case worked hard to develop the most appropriate geopolitical solution. They studied maps, statistics, histories, import-export charts, population data, and even sent American military personnel to investigate local conditions. And they decided, steadfastly and unflinchingly, that Fiume should go to the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (later to be known as Yugoslavia). They did not just tell Wilson this. They spelled it out in his “Little Black Book” of policies to champion. Their reasoning was mostly economic: Italy was already getting Trieste, the other large Adriatic Habsburg port, and Fiume was the only other Mediterranean port with railway connections from the Adriatic to central Europe and the Balkan peninsula. Moreover, though Fiume’s urban core counted more Italian-speakers than anything else, over 50% of the town itself did not identify as mother-tongue Italian. And if the city’s hinterlands were counted, it was Croatian and Slovene speakers who dominated, not Italians. In short, Wilson’s experts told the US president that if Italy got Fiume it would have a monopoly over Adriatic trade and tens of thousands of people who identified as South Slavs would be put under Italian sovereignty. Free-market Wilson needed to hear no more. This sounded like imperialism and bad business. It was decided: regardless of “autonomous” desires or “Italian lines of nationality,” Fiume would not go to Italy. In short, when it came to Fiume, the Paris talks were not about self-determination or nationality. They were about global free trade, and the Americans had made this decision about Fiume before anyone had walked into the negotiations.

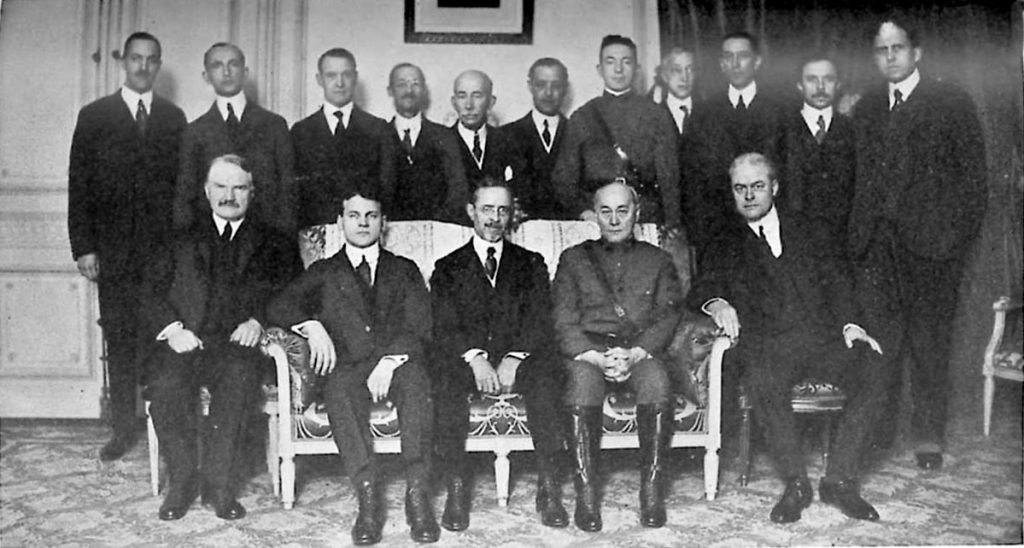

Photograph of Wilson’s expert team “The Inquiry” at the Paris Peace Conference. Sitting (left to right): Charles H. Haskins, Western Europe; Isaiah Bowman, Chief of Territorial Intelligence; S. E. Mezes, Director; James Brown Scott, International Law; David Hunter Miller, International Law; Standing: Charles Seymour, Austria-Hungary; R. H. Lord, Poland; W.L. Westermann, Western Asia; Mark Jefferson, Cartography; Colonel House; George Louis Beer, Colonies; D.W. Johnson, geography; Clive Day, Balkans; W. E. Lunt, Italy; James T. Shotwell, History; A. A. Young, Economics.

To Italians in Paris and within the Italian peninsula, this sounded like Wilson was going against the very Fourteen-Points values he had stated so self-righteously. With all the earmarks of American imperialism, it also seemed an injustice: there was one set of rules for the strongest countries (UK, France, USA) and another set for the rest. Very vocal segments of the Italian population felt like they were getting shafted, like their hard-fought, but glorious victory over Austria-Hungary was being “mutilated.” (This phrase, heard everywhere at the time, was coined by the same poet-dictator who would arrive so dashingly in Fiume just a few months later).

Things were tense. But then they got worse when Wilson made a serious diplomatic miscalculation. On April 23, 1919, after another fruitless, frustrating meeting with the Italian delegation, Wilson decided to go over the diplomats’ heads and directly ask Italians to demand their government relinquish Fiume to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. Against the advice of British, French, and American advisers—who pointed out that this direct appeal to a population is what leaders did when dealing with enemy governments, not allies—Wilson released to the newspapers a public plea asking Italians to trust him, to be generous on behalf of world peace, and give up Fiume.

The result was pandemonium. The Italian delegation walked out of the negotiations. The Italian public rallied against Wilson’s insult to their leaders and their rights to Fiume. International diplomacy fell apart. And Fiume became the symbol—the living diplomatic embodiment—of global bullying. For many Italians, even those who had never heard of the town before all the hubbub, Fiume became an emblem of national pride and international victimhood. Annexing Fiume quickly turned into a rallying cry for nationalist groups—many of whom were filled with disgruntled veterans and restless youth. “Fiume or death!” burst from the lips of ever more Italians. And activists in Fiume eager for annexation to Italy responded, “Italy or death!”

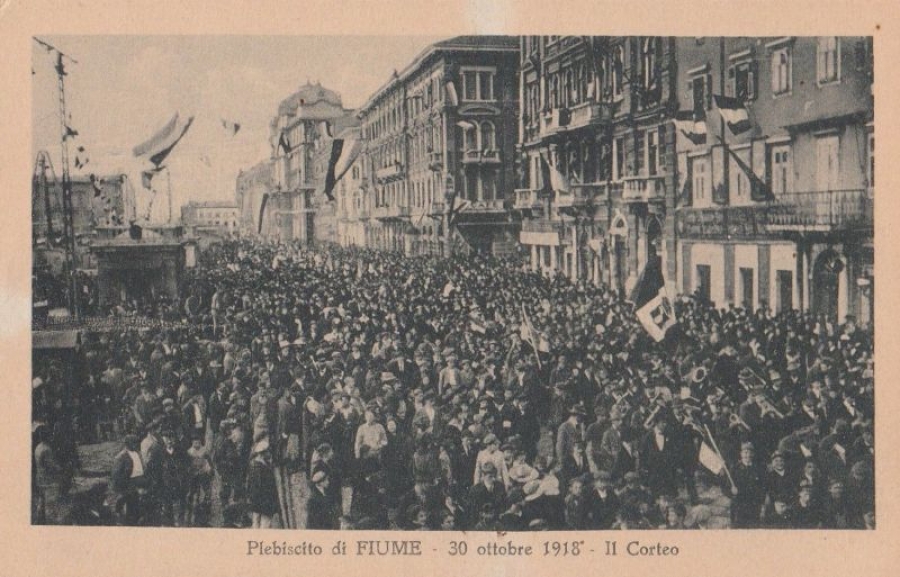

Postcard from 1919, featuring the public rally when the city’s Italian National Council (including most members of its municipal government) declared Fiume’s right to self-determination and intention to be annexed to Italy.

In this narrative, a clear path of Wilsonian missteps made the Fiume question the litmus test of Italian nationalism, turning it into the crisis of the liberal state. And this rendering isn’t entirely wrong. Wilson did bungle the Fiume question. His mishandling of Fiume also worsened conditions elsewhere. The Italian walkout forced him to yield to his Entente allies on other thorny questions. Conceding Japan a mandate in mainland China is one of the clearest mistakes that resulted from the need to stabilize the Entente after the Fiume pandemonium. The wildfire populism that associated Fiume with Italian international prestige was also due, in large part, to Wilson’s actions.

This is the story we know from studying diplomatic correspondence, newspapers, diaries, and memoirs. It is an important story, one in which the significance of American diplomatic maneuvers overshadows much. But this story doesn’t answer the base-level question that put the whole Fiume Crisis in motion before Wilson first deluded his Italian counterparts in Paris. Why did the city’s autonomous municipal government push to be annexed to Italy? And why did the city’s government continue to demand annexation for over 2 years even after Wilson made it clear this was not an option? These questions are especially important if we remember that at least half of the city’s population did not identify as Italian mother-tongue speakers, and Italy was a country increasingly known for its anti-Slavic nationalist tendencies.

November 1918, Fiume: One of the main squares in the town, covered with Italian (tricolor vertical) and Serb-Croat-Slovene (tricolor horizontal) flags. Here we see how the multiethnic city was filled also with people with many different ideas of what state they should be attached to. My book tries to answer the question of how such a diverse city did not explode into a hotspot city of urban violence.

To answer these questions, I turned away from yellow journalism and the “Big Man” diplomatic history that has dominated thus far and focused on what we can learn from the archives of daily life: police, court, port, hospital, schools, banks, chamber of commerce, etc. In doing so, the answers I’ve found for these questions—and many more—are surprising. What is clear from these records is that Wilson did not create the standstill, Fiumians did. Wilson might have said Italy would not get Fiume “so long as I am here,” but the Italian delegation and the Italian populace did not give up because Fiumians themselves kept pushing for their “autonomous right of self-determination.” Even under threats of blockade and isolation from international aid and food resources, Fiume’s municipal order did not fall apart, and the urban core did not devolve into the quicksand of civic violence we have come to expect from such situations. Fiume’s autonomous city government continued to push for inclusion into Italy no matter what presidents, prime ministers, or even Inter-Allied troops said. Chapters on money, law, citizenship, propaganda and education reveal centripetal forces that kept this multiethnic town’s workers, homemakers, businessmen, politicians, teachers, cobblers, and fishermen together so that the city could replace its dissolved Habsburg metropole with a new, Italian one.

From this perspective our interpretation of the Fiume Crisis’s import changes dramatically: far from being an example of how American diplomatic bumbling or extreme Italian nationalism stalled international efforts to create a stable nation-state order in post-1918 Europe, the Fiume case shows that the strongest impediment to Wilson’s plan for Europe lay in the longstanding imperial frameworks and mindsets that persisted, regardless of the fact that the empires that had created them had vanished from the map. On the ground, in the search for survival and a return to prosperity, somehow local infrastructures kept the city’s diverse population interdependent enough to support its drive against Wilson. Seen as a whole, my new book The Fiume Crisis: Life in the Wake of the Habsburg Monarchy demonstrates the breadth and limitations of the attempt to secure a future on a “ghost state’s” skeletal remains after its empire had suddenly disappeared. And the answer of who and why the Fiume Crisis shifts ever more away from Wilson and ever more towards the people who lost their Habsburg state and lived the postwar upheaval day-to-day in the hopes their former imperial state would be replaced by a new one.

Postcard of Fiume around 1900, featuring its main boulevard the Korzo (Corso in Italian).

Author Biography

Dominique Kirchner Reill received her PhD with Distinction from Columbia University and is currently Associate Professor of Modern European History at the University of Miami. Her first book, Nationalists Who Feared the Nation: Adriatic Multinationalism in Habsburg Dalmatia, Trieste, and Venice, was published by Stanford University Press in 2012 and received the 2014 Book Prize from the Center for Austrian Studies, as well as Honorable Mention from the 2012 Smith Award. Her new book, The Fiume Crisis: Life in the Wake of the Habsburg Empire, comes out December 1, 2020 with Harvard University’s Belknap Press. She is an Associate Review Editor for the American Historical Review, editor for the Purdue University Press book series Central European Studies, and member of the editorial board for the Cambridge University Press journal Contemporary European History. Currently, she is a Visiting Scholar at the European University Institute, where she is conducting research for her next book, The Habsburg Mayor of New York: Fiorello LaGuardia.

Further Reading

Borut Klabjan, ed., Borderlands of Memory: Adriatic and Central European Perspectives (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2018).

Daniela Rossini, Woodrow Wilson and the American Myth in Italy: Culture, Diplomacy, and War Propaganda, Harvard Historical Studies (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008).

J. N. Macdonald, A Political Escapade: The Story of Fiume and D’Annunzio (London: J. Murray, 1921).

Larry Wolff, Woodrow Wilson and the Reimagining of Eastern Europe (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2020).

Michael Arthur Ledeen, The First Duce: D’Annunzio at Fiume (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977).

Paul Miller and Claire Morelon, eds., Embers of Empire: Continuity and Rupture in the Habsburg Successor States after 1918 (New York: Berghahn Books, 2018).

Pieter M. Judson, The Habsburg Empire: A New History (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016).

Robert Gerwarth, The Vanquished: Why the First World War Failed to End (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016).

Tea Perinčić, Rijeka ili smrt! (D’Annunzijeva okupacija Rijeke 1919.-1921.) Rijeka or death! (D’Annunzio’s occupation of Rijeka, 1919-1921), (Rijeka: Naklada Val, 2020).

Wesley J. Reisser, The Black Book: Woodrow Wilson’s Secret Plan for Peace (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books 2012).

Most Important Archives Consulted in the Writing of this Book

HR-DARI: Hrvatski Državni Arhiv u Rijeci (Croatian National Archives in Rijeka)

AFV: Vittoriale degli italiani- Archivio fiumano (Vittoriale of the Italians Fiume Archive)

JHSC: Johns Hopkins Special Collections

Notes

[1] John Maxwell Hamilton and Robert Mann, A Journalist’s Diplomatic Mission: Ray Stannard Baker’s World War I Diary (from Our Own Correspondent) (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2012), 326.

[2] Lawrence E. Gelfand, The Inquiry: American Preparations for Peace, 1917–1919 (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1976), 327.

Images (full captions)

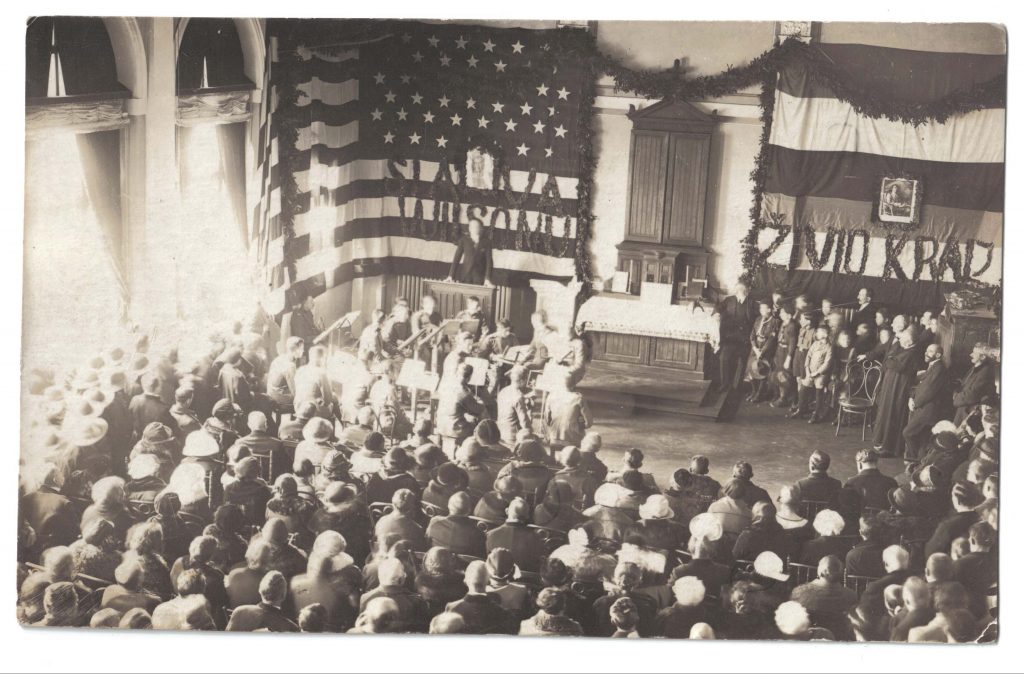

1) Map of Fiume before the end of World War I, when the semiautonomous city-state was part of Habsburg Hungary. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/64/Fiume_town_map.jpg

2) Picture of Italians preparing to celebrate Wilson’s arrival in Rome, when Italians thought the Fourteen Points would support much of their hopes for territorial expansion in the Adriatic. [January 4, 1919] Flags and people in the Coliseum, Rome, Italy during the visit of President Woodrow Wilson on January 4, 1919https://www.reddit.com/r/100yearsago/comments/achm4d/january_4_1919_flags_and_people_in_the_coliseum/

3 ) South Slav activist meeting in Sušak, a town outside Fiume, probably April 1919, with an American flag proudly displayed and a picture of Wilson in the middle, with the writing saying “Long Live Wilson!” It’s unclear why the flag is backward. The other flag is that of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes with a picture of their king in the center. (Photo courtesy of Pomorskog i povijesnog muzeja Hrvatskog primorja Rijeka)

4) Photograph of Wilson’s expert team “The Inquiry” at the Paris Peace Conference. Sitting (left to right) : Charles H. Haskins, Western Europe; Isaiah Bowman, Chief of Territorial Intelligence; S. E. Mezes, Director; James Brown Scott, International Law; David Hunter Miller, International Law; Standing: Charles Seymour, Austria-Hungary; R. H. Lord, Poland; W.L. Westermann, Western Asia; Mark Jefferson, Cartography; Colonel House; George Louis Beer, Colonies; D.W. Johnson, geography; Clive Day, Balkans; W. E. Lunt, Italy; James T. Shotwell, History; A. A. Young, Economics. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Inquiry#/media/File:Inquiry_members_at_the_Paris_Peace_Conference_1919.jpg

5) Postcard from 1919, featuring the public rally when the city’s Italian National Council (including most members of its municipal government) declared Fiume’s right to self-determination and intention to be annexed to Italy.

6) November 1918 Fiume: One of the main squares in the town, covered with Italian (tricolor vertical) and Serb-Croat-Slovene (tricolor horizontal) flags. Here we see how the multiethnic city was filled also with people with many different ideas of what state they should be attached to. My book tries to answer the question of how such a diverse city did not explode into a hotspot city of urban violence. (from author’s collection)

7) Postcard of Fiume around 1900, featuring its main boulevard the Korzo (Corso in Italian).

Published on December 1, 2020.