Part III of Megan Brandow-Faller’s Interwar Vienna’s ‘Female Secession’: From Vienna to New York and Los Angeles

By Megan Brandow-Faller

PART III

Emmy Zweybrück-Prochaska and Liane Zimbler, who both played leading roles in Wiener Frauenkunst (WFK) Raumkunst exhibitions also left Austria for New York and Los Angeles. Like the exiled ceramicists, Zweybrück-Prochaska’s reputation as a pedagogue, designer, and craftswoman preceded her forced emigration. Throughout the 1930s, Zweybrück-Prochaska had taught seminars and summer courses on art instruction for children throughout the United States, serving as a guest lecturer at Columbia University, the University of Southern California, the University of California-Los Angeles, the University of Texas, Rhode Island School of Design, and elsewhere. Zweybrück-Prochaska, whose paternal grandfather was a Jewish convert to Christianity, never returned from her last American lecture tour in Spring 1939, despite applying for the renewal of her school’s rights of public incorporation for the 1939/40 school year prior to her departure.[1] While her non-Jewish husband, entrusted with the administrative leadership of the school, claimed that the outbreak of war prevented her from returning, Zweybrück-Prochaska’s racial classification as Mischling (mixed blood) made membership in the Reichskulturkammer impossible, suggesting that her extended 1939 stay with her daughter, Nora, born in 1921, was deliberate.

In American exile, her publications like The Stencil Book: The Modern Art Methods of Professor Emmy Zweybrück (1935) and Hands At Work (1942) encouraged teachers and parents to free the spark of creative genius slumbering in every child. As artistic director of the American Crayon Company from 1939 to 1956 and editor of Everyday Art, a promotional journal directed to schoolteachers, Zweybrück-Prochaska disseminated the secessionist discovery of child art to a wide public in the postwar American cult of the creative child.[2] Working as artistic consultant to stores including Marshall Fields, Neiman Marcus, B. Altman, Lord & Taylor, and R. H. Macy’s, Zweybrück-Prochaska continued to advance her ideas on the expressive possibility of ornament through new surface designs and publications calling for a reaction against the sober practicality of the machine aesthetic. Articles published in Everyday Art demonstrated simple ‘DIY’ techniques for stenciling and silk screen printing of household textiles in an effort to reintroduce a sense of homey domesticity back into the modern interior. Following her example, modern women were enjoined to discover a lost heritage of female handcrafts, relearning, reinventing, and reclaiming old needlework techniques while taking inspiration from tribal peoples and folk cultures.[3] In 1955, Zweybrück-Prochaska was honored for her role in promoting Austrian applied arts and handcraft abroad with a collective exhibition at the Vienna Secession. Living between the American Crayon Company’s headquarters in New York and Los Angeles, where she commissioned Richard Neutra to design an open-layout building reflecting the company’s commitment to progressive art instruction, Zweybrück-Prochaska admitted shortly before her death that, despite the hardships of exile, she felt more energetic, youthful, and productive than ever during her second career in America.[4]

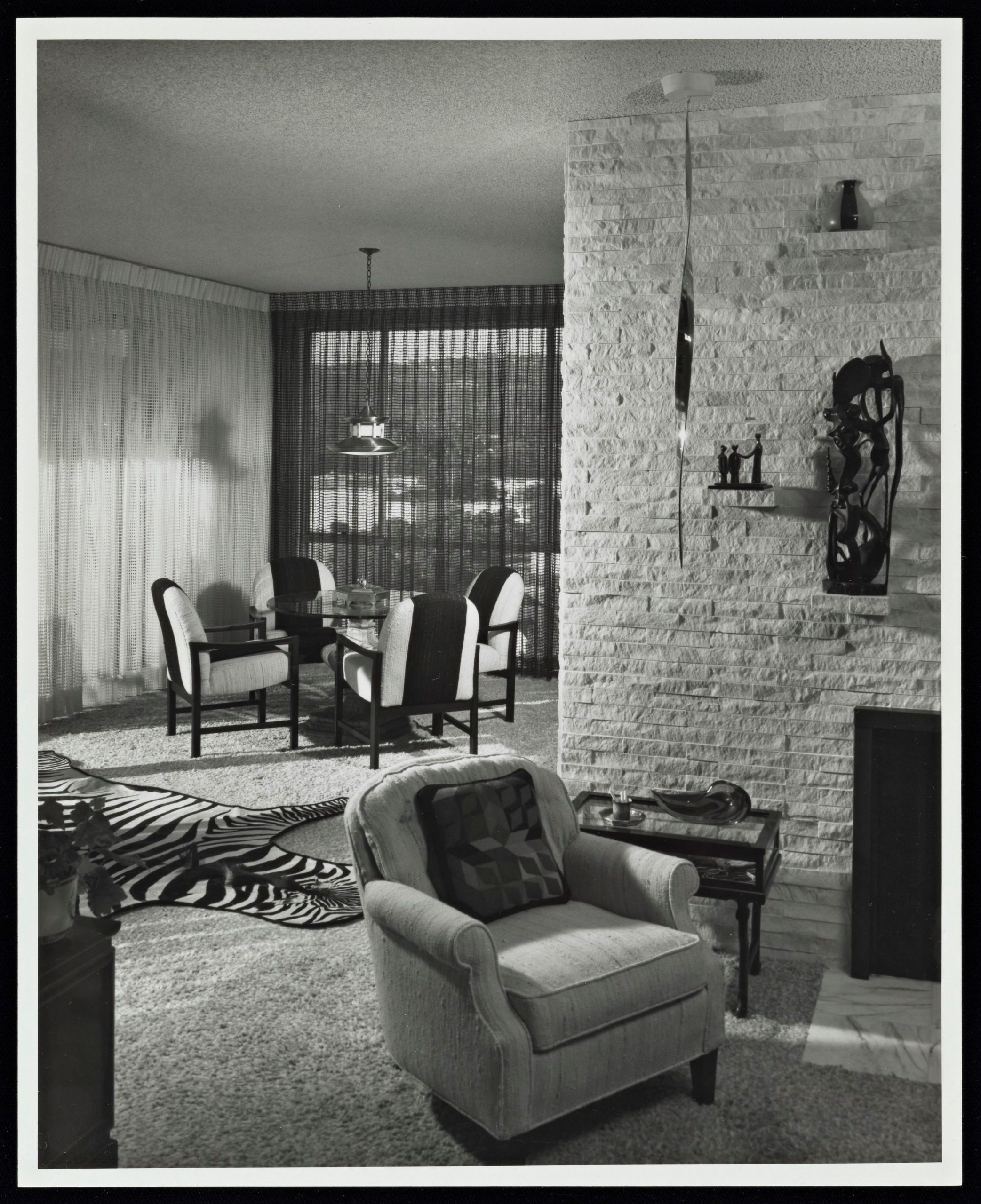

Fleeing to Los Angeles through London and New York, architect Zimbler moved in the same circles as Zweybrück-Prochaska and Susi Singer. A series of newspaper articles on the “visiting lady architect from Old Vienna” treated her as a curiosity, likening her family’s path of migration after the Anschluss to a sightseeing journey while drawing attention to her anomalous position in a male-dominated field.[5] One such article, “LA is Home For Europe’s First Woman Architect,” detailed how Zimbler, despite facing ridicule and patronizing treatment as an “amusing” oddity, was able to succeed by “work[ing] harder than any man.”[6] Female club networks, including the Los Angeles chapter of the Soroptimist International and the National Council of Jewish Women, facilitated contacts to architects like Neutra and Rudolf Schindler and invited her to lecture on architecture, design, and women’s professional life.[7] Like in her Viennese practice, Zimbler focused on interior design, remodeling and adapting existing structures, similarly incorporative decorative elements like printed floral textiles and decorative ceramics into her otherwise sober interiors. She received many commissions by members of the Austro-German exile community, including writer Vicki Baum, composer Ernst Toch, and some of her Viennese clients, many of whom, like Zimbler, were Jews.[8] Like Vally Wieselthier, Zimbler’s engagement with professional design organizations brought the spirit of WFK Raumkunst exhibitions to America; the architect participated in the National Council of Jewish Women’s Living With Famous Paintings series, an analogue to the WFK’s 1929 show, and other exhibitions of complete model interiors organized by the American Institute of Decorators.[9] Like Zweybrück-Prochaska, Zimbler seemed proud of her ability to flourish in exile, especially in the male-dominated field of architecture, and demonstrated remarkable resilience in adapting to postwar conditions.

Decorative handcrafts, a traditional site of femininity, are commonly associated with an image of unthreatening docility. But the artists connected with interwar Vienna’s ‘female Secession’ created artworks that disrupted established boundaries between ‘high’ and ‘low,’ function and utility, and masculine and feminine fields of expression. It is my intent, then, in The Female Secession, not to reify the monographic approach through the works of individual artist-designers, but to recapture the radical potential of what Fanny Harlfinger-Zakucka referred to as ‘works from women’s hands’ in putting forth an alternative version of Viennese modernism that never turned on its ornamental, decorative roots.

Author Biography:

Megan Brandow-Faller is Associate Professor of History (with tenure) at the City University of New York, Kingsborough. Her research focuses on art and design in Secessionist and interwar Vienna, including children’s art and artistic toys of the Vienna Secession; expressionist ceramics of the Wiener Werkstätte; folk art and modernism; and women’s art education. She is the editor of Childhood by Design: Toys and the Material Culture of Childhood, 1700-present (Bloomsbury 2018) and the author of The Female Secession: Art and the Decorative at the Viennese Women’s Academy (Penn State University Press, 2020).

To learn more, please visit: https://www.meganbrandowfaller.com/

Notes

[1] Emmy Zweybrück-Prochaska to the Stadtschulrat f. Wien, 7 January 1939; Reichsstaathalter in Wien to the Kunstgewerbliche Lehranstalt Emmy Zweybrück-Prochaska, 28 November 1939, UAKS.

[2] Amy Ogata, Designing the Creative Child: Playthings and Places in Midcentury America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 154.

[3] Emmy Zweybrück-Prochaska, “Die künstlerische Handarbeit.” Die Pause 1, no. 4 (November 1935): 42–44; “Über moderne Handarbeit.” Neues Wiener Tagesblatt, 6 Dec 1933, 17.

[4] Hans Ankwicz-Kleehoven, “Introductory Remarks for the Opening of the Collective Exhibition of Prof Emmy Zweybrück,” 4 June 1955, n.p. Nachlass Hans Ankwicz-Kleehoven, ÖGBA (Österreichische Galerie Belvedere Archiv)

[5] These articles are preserved in the IAWA (International Archive of Women in Architecture, Virginia Technical University) and the ÖGBA.

[6] “LA is Home for Europe’s First Woman Architect,” [name of newspaper is lost], Nov. 25, 1949, MS 1988 005, box 2, folder 11, IAWA.

[7] Sabine Plakolm-Forsthuber, “Ein Leben, Zwei Karrieren: Die Architektin Liane Zimbler.” In Visionäre und Vertriebene: Österreichische Spuren in der modern amerikanischen Architektur, edited by Matthias Boeckl, 295–309 (Berlin: Ernst and Sohn, 1995), 301.

[8] Christina Gräwe, “Porträt—Liane Zimbler.” Die alte Stadt 31, no. 2 (2004): 139–45.

[9] Sabine Plakolm-Forsthuber, “Ein Leben,” 300.

Image Caption

Shulman, Julius, Photographer, and Zimbler, Liane, Architect. Job 5166: Liane Zimbler, Barrett Condominium (Beverly Hills, Calif.), 1974 (1974). Web.