The Jungle in Pilsen

By Alison Orton

At the turn of the century, the poor working conditions at breweries in the Habsburg Empire’s western Bohemian city of Pilsen (Plzeň) gained international attention, especially after Samuel Gompers, a prominent American labor activist, toured Pilsen’s breweries in 1909. Following his visit to Pilsen, Gompers wrote that beer drinkers around the world should abstain from beer made in Pilsen until working conditions improved.[1] Svazový List, a Czech Language newspaper for brewery workers published by the Austrian Union of Brewery Workers, attempted to mobilize support for their organization with a comparison to Upton Sinclair’s description of Chicago’s meat packing industry in The Jungle: “The Jungle [dealt] with the terrible scenes in the lives of workers employed in Chicago slaughterhouses. . .the world famous beer city of Pilsen is a similar Jungle.”[2] In this first of three posts in which I explore the circumstances faced by brewery workers who migrated from the Habsburg Empire to the United States, I examine the factors that compelled them to emigrate from Pilsen, beginning with a brief description of the working conditions.

Following the visits to Pilsen by Gompers and other American labor activists, working conditions and low wages in breweries gained greater attention beyond the borders of the Habsburg Empire. The United States National Union of Brewery Workmen [NUBW], the largest and most influential brewery workers’ union in the US, kept a close watch on the conditions, especially in Pilsen, reporting that workers lived locked behind brewery gates and worked in conditions “worse than slavery.”[3]

Despite the international attention, attempts by labor organizers to improve wages and conditions in Pilsen and other major beer producing centers only exacerbated anti-labor sentiment in the region’s largest breweries. Anti-labor sentiment, in turn, contributed to the migration of brewery workers from the Czech Lands to the United States during the period of heavy migration in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth centuries.

During peak seasons, brewery workers worked 16 hours per day, seven days a week with only four-hour breaks between shifts. At Pilsen’s major breweries, workers lived in bunk rooms behind brewery walls that housed rotations of 14 workers by shift. These rooms were rarely unoccupied for more than an hour at a time. Because of the damp conditions necessary for the brewing process, the bunkrooms were described as constantly wet, moldy, and unbearably smelly with no ventilation.[4] Workers had no place to dry their damp clothes and shoes during their brief four hours of rest. Additionally, brewery work included several inherent dangers ranging from vats of hot liquid to slippery cold cellar floors, to towering barrels of beer that could roll back onto workers.

Reports of accidents at breweries circulated widely. One publicized example was that of Šimon Štilip, an employee of Pilsen’s Měšťanský Pivovar. While working alone, Štilip fell through a grate into a little-used part of the labrynthine cellar tunnels under the brewery. Nobody searched for him for two days, and, according to doctors, he died slowly from his injuries but would have survived had he received medical attention in the first few hours. A Pilsen area newspaper, Naše Snahy, speculated that if a barrel of beer had gone missing for even two hours, much less two days, the whole brewery would have been searching for the missing product.[5]

Despite the bad working conditions, greater international publicity about these conditions, and the growing popularity of labor unions in the late 19th– and early 20th centuries, very little changed for brewery workers in major breweries in Bohemia and Moravia. In part because of growing nationalist strife among trade unions, brewery management in these regions easily squashed union organizing efforts and blacklisted workers identified with any union activity. Once blacklisted for labor activism, a worker found it difficult to work in breweries throughout the Habsburg Empire. The blacklisting of brewery workers forced many who hoped to continue their occupations as brewers and maltsters to migrate outside of Austria-Hungary. The United States was a common destination until the outbreak of WWI and the adoption of prohibition.

Many brewery workers only reluctantly left their homeland, despite the poor working conditions. One migrant, Karel Groušl, who was fired and blacklisted by the Měšťanský Pivovar in Pilsen wrote an open letter to Pilsen’s brewers that was published in a Czech-language brewery workers’ newspaper called Rozhledy. In his letter, Groušl wrote that “you forced me to leave my homeland and go abroad you chase[d] legions of workers from our homeland.”[6] Groušl’s sentiment echoed in migrant brewery workers’ stories.

For brewery workers who felt compelled to migrate and for whom organized labor was a priority, the United States was an attractive alternative to the Czech Lands. By 1900, 93% of brewery workers in the United States worked under contracts negotiated by the United States NUBW, making it one of the most successful unions in the US.[7] While acknowledging that brewery work was inherently dangerous, the NUBW fought for and won improvements in working hours, workplace safety, wages, as well as a decrease in child labor within US breweries by 1910.[8]

News of the successes of the NUBW traveled across the ocean and the union received glowing praise as a model union in brewery workers’ papers in the Habsburg Empire.[9] And the NUBW welcomed immigrant brewery workers, especially those from the lager beer producing regions of Central Europe. NUBW literature expressed great pride in the Central European roots of the United States brewing industry as a whole, stating that it was necessary for both the industry and the labor union “to remain in the closest touch with the new . . . immigrant elements” who would be both the chief producers and consumers for the relatively new lager beer in the United States.[10]

Yet the NUBW looked at one subset of immigrant brewery workers from the Habsburg Empire with suspicion. In 1912, the NUBW even passed a resolution that automatically labeled hundreds of immigrant workers as potential scabs and strikebreakers.[11] This resolution effectively ended the employment prospects of this subset of migrants. In my next post, I will examine why this one particular subset of immigrant brewery workers were turned away from employment upon arriving at local union offices in the United States.

Author Bio:

Alison is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at the University of Illinois at Chicago. In her dissertation, beer and the brewing industry are lenses through which to examine the fluidity of national and ethnic attachments among the popular classes in the Czech Lands during the last years of the Habsburg Empire, and in the course of migration to the United States.

Further Reading:

Beneš, Jakub. Workers and Nationalism: Czech and German Social Democracy in Habsburg Austria, 1890-1918. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Judson, Pieter. The Habsburg Empire. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2016.

Mittelman, Amy. Brewing Battles: A History of American Beer. New York: Algora Publishing, 2008.

Schlüter, Hermann. The Brewing Industry and the Brewery Workers’ Movement in America, Cincinnati: S Rosenthal and Co., 1910.

Steidl, Annemarie, Wladimir Fischer-Nebmaier, and James W. Oberly. From a Multiethnic Empire to a Nation of Nations: Austro-Hungarian Migrants in the US, 1870-1940. Innsbruck: Studienverlag, 2017.

Zahra, Tara. The Great Departure: Mass Migration from Eastern Europe and the Making of the Free World. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2016.

Archival Sources:

Fach 15: Aus- und Einwanderung, Haus- Hof- und Staatsarchiv, Vienna, Austria

Fach 91: Spiritus und Alkohol, Haus- Hof- und Staatsarchiv, Vienna, Austria

United Brewery Workers Records, IBT Labor History Research Center, George Washington University, Washington, D.C., United States

[1] Samuel Gompers, Labor in Europe and America (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1910), 91.

[2] “Tisk pivovarského dělnictva v cizině o poměrech v Plzni,” Svazový List, January 5, 1912

[3] Proceedings for the National Union of Brewery Workmen National Convention, September 1912, Series 2, Box 3, Folder 2, United Brewery Workers Records, IBT Labor History Research Center, George Washington University, Washington, D.C.

[4] See, for example “Der Weltruf Pilsens,” Brauerei Arbeiter Zeitung, September 9, 1911; “K světové pověsti měšťanského pivovaru v Plzni,” Rozhledy pivovarského Dělnictva, April 4, 1910; “K “plzeňským poměrům,” Svazový List, December 22, 1911.

[5] “Měšťanský pivovar v Plzni a dělnici,” Naše Snahy, September 25, 1899.

[6] “Amerika,” Rozhledy pivovarského dělnictva, June 15, 1908.

[7] Proceedings for the National Union of Brewery Workmen National Convention, 1910, Series 2, Subseries 1, Box 3, Folder 1, United Brewery Workers Records, IBT Labor History Research Center, George Washington University, Washington, D.C.

[8] Schlüter, Hermann. Brewing Industry and the Brewery Worker’s Movement in America, Cincinnati, 1910, 268-274.

[9] “Průmysl pivovarský a hnutí dělnictva pivovarského v Americe,” Rozhledy pivovarského Dělnictva, August 3, 1910; “Vývoj pivovarského průmyslu a organisace pivovarského dělnictva v Americe,” Svazový List, August 12, 1912.

[10] Schlüter, Hermann. Brewing Industry and the Brewery Worker’s Movement in America, Cincinnati, 1910, 68-69.

[11] Proceedings for the National Union of Brewery Workmen National Convention, September 1912, Series 2, Box 3, Folder 2, United Brewery Workers Records, IBT Labor History Research Center, George Washington University, Washington, D.C.

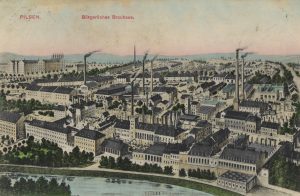

Postcard of the Měšťanský Pivovar/Bürgerliches Brauhaus in Pilsen, circa 1910.

“ Bürgerliches Brauhaus” by Hermann Seibt, Melssen, 10,000 postcards from Germany circa 1900, Wikimedia Commons, accessed March 24, 2019.